Atheism and Ethics

A WORLD WITHOUT RELIGION?

The question is whether an atheist world would be a better world.

Slavoj Zizek, atheist philosopher, refers to René Girard’s analysis of Christianity in God in Pain: Inversions of Apocalypse and concludes that Christianity, revealing the innocence of erstwhile sacrificial victims, “[undermines] the efficiency of the entire sacrificial mechanism of scapegoating: sacrifices (even of the magnitude of a holocaust) become hypocritical, inoperative, fake…” As this sacrificial mechanism is the cornerstone of religious behavior, Christianity thus indeed is “the religion of the end of religion” (atheist historian Marcel Gauchet). Zizek, still in the aforementioned essay, also briefly explains how Christianity potentially brings to an end the ever- present sacrificial temptation: “Following René Girard, Dupuy demonstrates how Christianity stages the same sacrificial process [of archaic religion], but with a crucially different cognitive spin: the story is not told by the collective which stages the sacrifice, but by the victim, from the standpoint of the victim whose full innocence is thereby asserted. (The first step towards this reversal can be discerned already in the book of Job, where the story is told from the standpoint of the innocent victim of divine wrath.)” This assessment of Christianity could also help to understand Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s call for a “religionless Christianity” (or maybe we should speak of a Christianity transforming religion rather than destroying it – click here for more).

Slavoj Zizek, atheist philosopher, refers to René Girard’s analysis of Christianity in God in Pain: Inversions of Apocalypse and concludes that Christianity, revealing the innocence of erstwhile sacrificial victims, “[undermines] the efficiency of the entire sacrificial mechanism of scapegoating: sacrifices (even of the magnitude of a holocaust) become hypocritical, inoperative, fake…” As this sacrificial mechanism is the cornerstone of religious behavior, Christianity thus indeed is “the religion of the end of religion” (atheist historian Marcel Gauchet). Zizek, still in the aforementioned essay, also briefly explains how Christianity potentially brings to an end the ever- present sacrificial temptation: “Following René Girard, Dupuy demonstrates how Christianity stages the same sacrificial process [of archaic religion], but with a crucially different cognitive spin: the story is not told by the collective which stages the sacrifice, but by the victim, from the standpoint of the victim whose full innocence is thereby asserted. (The first step towards this reversal can be discerned already in the book of Job, where the story is told from the standpoint of the innocent victim of divine wrath.)” This assessment of Christianity could also help to understand Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s call for a “religionless Christianity” (or maybe we should speak of a Christianity transforming religion rather than destroying it – click here for more).

In other words, Christianity is – in a profound sense – one of the main sources of secularization. Secular societies are challenged to build a world without “sacred sacrifices”. As Zizek notes, “the sacred sacrifice to the gods is the same as an act of murder – what makes it sacred is that it limits/contains violence, including murder, in everyday life.” Precisely because a secular society, heir to the dismantlement of “the archaic sacred” by Christianity, no longer possesses the traditional religious means to contain violence, it has to find other ways to deal with violence, or else destroy itself. Zizek quotes Jean-Pierre Dupuy in this regard: “Concerning Christianity, it is not a morality but an epistemology: it says the truth about the sacred, and thereby deprives it of its creative power, for better or for worse.” And Zizek continues: “Therein resides the world-historical rupture introduced by Christianity: now we know [the truth about the sacred], and can no longer pretend that we don’t. And, as we have already seen, the impact of this knowledge is not only liberating, but deeply ambiguous: it also deprives society of the stabilizing role of scapegoating and thus opens up the space for violence not contained by any mythic limit.”

(Quotes from Zizek in Slavoj Zizek & Boris Gunjevic, God in Pain: Inversions of Apocalypse – [Essay] Christianity Against the Sacred, Seven Stories Press, New York, 2012, p. 63-64).

With these thoughts in mind, we can frame the question about the atheist world in another way. Can our world survive its own potential for violence without religion, without the traditional sacrificial mechanisms that try to limit violence?

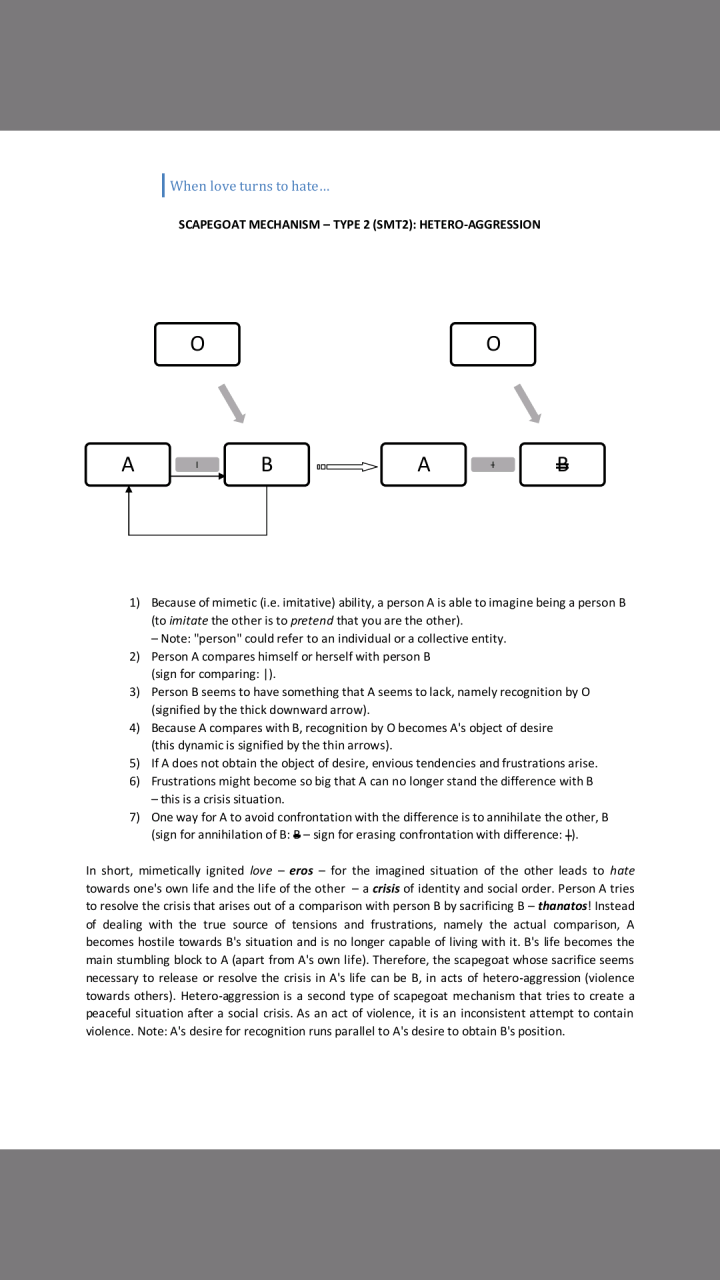

NEW ATHEIST RELIGION & AMORAL ATHEISM

As it happens, we seem to regenerate the religious impulse. To this day we keep looking for scapegoats to be cast out of society in order to purify ourselves from the evils in our midst. It’s part of the way we build ‘the City of Man’. Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens, two well-known spokesmen of the so-called ‘New Atheism’, clearly consider religion as one of the main sources of evil in the world. Hence, in their views, we would be better off without religion. But, precisely because of their tendency to blame theistic religion for “much of the evil in the world” and their attempts to expel or even sacrifice it, they create a new sacrificial religion, albeit an atheist one. How long before believers – without whom their theistic religion would not exist – no longer have the right to voice their views in the public sphere if the new atheists had their way?

As it happens, we seem to regenerate the religious impulse. To this day we keep looking for scapegoats to be cast out of society in order to purify ourselves from the evils in our midst. It’s part of the way we build ‘the City of Man’. Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens, two well-known spokesmen of the so-called ‘New Atheism’, clearly consider religion as one of the main sources of evil in the world. Hence, in their views, we would be better off without religion. But, precisely because of their tendency to blame theistic religion for “much of the evil in the world” and their attempts to expel or even sacrifice it, they create a new sacrificial religion, albeit an atheist one. How long before believers – without whom their theistic religion would not exist – no longer have the right to voice their views in the public sphere if the new atheists had their way?

The demonization of theistic religion by the new atheists is their way of suggesting the moral superiority of atheism. Their reasoning, however, is flawed and incomplete. Take, for instance, this challenge by Christopher Hitchens:

“Name one ethical statement made, or one ethical action performed, by a believer that could not have been uttered or done by a nonbeliever. And here is my second challenge. Can anyone think of a wicked statement made, or an evil action performed, precisely because of religious faith?”

Some people, thinking of the atrocities committed by Stalin, Mao and Pol Pot, try to make this a more balanced rhetorical statement by adding a question: Can anyone think of a wicked statement made, or an evil action performed, precisely because of atheism?

The new atheists already have their response to those who think that the crimes of Stalin et al. had anything to do with atheism. Richard Dawkins:

“What I do think is that there is some logical connection between believing in God and doing some, sometimes, evil things, but there’s no logical connection between them [Stalin, Mao, and Pol Pot] being atheists and doing evil things. It’s just incidentally true that, say, Mao Zedong and Joseph Stalin happened to be atheists, but that wasn’t what drove them. What drove them was a political ideology. It had nothing to do with atheism.”

Another atheist puts it this way:

“While Stalin and Mao were atheists, they did not perpetrate their atrocities because of their atheism. Atheism is simply the lack of belief in god. One cannot commit a crime in the name of ‘there is no god’. On the other hand, one can commit a crime in the name of ‘god’.”

This statement also implies that nothing good can be done in the name of atheism. Atheists can do good things like believers can do good things. The difference is that believers can do good things “in the name of god”. Atheists can do bad things like believers can do bad things. The difference is that believers can do bad things “in the name of god”. But, just like crimes cannot be done in the name of “there is no god”, good deeds cannot be done in the name of “there is no god”. Atheism is not immoral, neither is it moral. Atheism is amoral – it literally has no moral implications.

Therefore, it is not guaranteed that an atheist world would be a better world. It all depends on the ethics that will be developed in such a world. Moreover, theists and atheists alike can only believe that one ethical decision or even system is better than another. They can never prove this. Science observes and describes facts, it doesn’t morally judge them – we cannot move from what is to what ought. We’ve already seen the ethics of Stalin’s political ideology, to name but one example, and it’s highly questionable whether that was a good thing… And if we would put some of the new atheist ideas into practice, we would regenerate a sacrificial system of potentially apocalyptic proportions. Sam Harris, for instance:

“Some propositions are so dangerous that it may even be ethical to kill people for believing them. This may seem an extraordinary claim, but it merely enunciates an ordinary fact about the world in which we live. Certain beliefs place their adherents beyond the reach of every peaceful means of persuasion, while inspiring them to commit acts of extraordinary violence against others. There is, in fact, no talking to some people. If they cannot be captured, and they often cannot, otherwise tolerant people may be justified in killing them in self-defense. This is what the United States attempted in Afghanistan, and it is what we and other Western powers are bound to attempt, at an even greater cost to ourselves and to innocents abroad, elsewhere in the Muslim world. We will continue to spill blood in what is, at bottom, a war of ideas.“

Seen from the perspective of René Girard’s mimetic theory, these ideas of new atheists mirror the ideas of some of their fundamentalist counterparts (for more on this, click here to read and watch Religulous Atheism). The tiny proportion of theistic fundamentalists that take part in acts of violence justify their violence in a similar way. They think it is ethical to kill certain people in order to cleanse the world of evil. New atheists and theistic fundamentalists become mimetic (i.e. imitative) doubles – imitating each other’s ways of scapegoating. However, as a wise man once said, “Satan cannot cast out Satan”. We cannot destroy (the possibility of) violence by using violence. We cannot destroy fear if our politics of security justify themselves by constantly referring to the things we should be afraid of. We cannot destroy evil by using evil.

In the end we’ll have to imagine a new peace, but not the (theist and atheist religious) peace of “this world”, which is based on sacrifice. It might be the peace this man speaks of:

“Peace I leave with you; my peace I give you. I do not give to you as the world gives. Do not let your hearts be troubled and do not be afraid.” (John 14:27)