White Privilege on the Right and the Left – A Lesson from Malcolm X

White Privilege Forgotten by the Right

I’ve had students defend their rather negative attitude at school like this:

“High school is a time for rebellion. As a high school kid, you should disobey your teachers in order to discover yourself. Perhaps most of all, high school is a time for pranks and practical jokes.”

Anthropological considerations aside, from a socio-economic perspective this type of attitude towards high school is often a sign of privilege. Some parents even encourage their children to “experiment” at the very spot where their offspring should be preparing for the future. And by experimenting they don’t mean developing philosophical thought experiments or exploring a scientific hypothesis. They rather refer to a kind of mischief that is supposed to build a strong character and personality. When teachers complain about the conduct of their children, those types of parents either pretend to agree with the teachers or they try to excuse the misconduct by using phrases like “we’ve all been young” and “with youth comes youthful indiscretion…” Those parents know that what their children don’t learn at school, they will learn from high paid tutors who eventually get them into university.

Apart from developing the weak spine of a spoilt brat, adolescents who grew up that way didn’t do anything else but imitate the kind of behavior that is advertised in pop culture time and again. We all develop an identity by mimetic (i.e. imitative) processes, of course, but it is quite ironic that the high school rascal thinks of himself as an original and daring character. This is the typical narcissism of the youngster who thinks of himself as a hero and doesn’t see that there is nothing heroic about “transgressing rules” at most of today’s permissive high schools. He is unable to love the reality of his situation, but is all the more in love with an unrealistic self-image of which he wants the confirmation by his peers. In the end, however, his eventual professional ambitions are often not “original” at all, as they turn out to be imitations of the ambitions of his parents and their social network.

When children come from a poor neighborhood and have to walk 10 miles a day to the nearest school, they don’t have the luxury to waste the precious time and money that their community invests in providing a good education. As it happens, some of those disadvantaged children end up at schools surrounded by rich kids who behave like so-called high school rebels. However, the poor child who starts imitating his “rebellious” classmates does not have the resources to compensate for the potential voids in his education as a consequence of his so-called rebellious behavior. There is not an army of high paid tutors waiting at home.

Moreover, in the process of growing up the disadvantaged kid will also start noticing that his mischief is separated from the same mischief committed by privileged youth of the same age group. Indeed some rich parents who do excuse the misconduct of their own children as “youthful indiscretion” will condemn the same behavior as “juvenile delinquency” when it is performed by so-called uneducated poor people, even more so when these are people of color. Racism runs deep. Add to this the fact that a lot of socio-economic problems today in communities of colored people are the consequence of a history dominated by white elites, and it becomes clear why a movement against discrimination calls itself Black Lives Matter to create “privilege for all” and not predominantly “white”.

People on the political right should be more aware of the double standard behind blaming disadvantaged people for their own miserable situation. The fact of the matter is that opportunities are not equal for all. Some enjoy the privilege of getting away with so-called “youthful indiscretions”, for instance, while others are incarcerated for the very same youthful sins. Those types of privilege are often forgotten by the political right. Also, if we would truly live in a meritocratic society, and not just on paper, the likes of Donald Trump would never make it into the US presidential office (even if they were backed by powerful elites who were planning to use that type of president to push their own agenda).

In a worst case scenario, the downtrodden develop a deep-seated feeling of ressentiment. They develop an aversion to the ambitions they previously imitated from their privileged peers. They comfort themselves by getting a sense of self-worth in groups that claim to oppose everything privileged people stand for. As a privileged elite points to their mistakes and blames them for their miserable condition, while at the same time that privileged elite can afford making similar mistakes without having to pay for them, they are easily manipulated by recruiters who abuse their sense of victimhood. They fall for the basic story of every manipulator: “They reject you, but I see your potential…” Thus they become the slaves of false Messiahs who promise to deliver them from victimhood, but who actually keep the victimary status alive to gain power over their followers. Gangs thrive upon ressentiment, from ISIS to the Black Disciples to groups of Neo-Nazis.

It is important to realize that the violence originating from ressentiment cannot be disconnected from instances of systemic violence and oppression as described above. Ressentiment ultimately results from a comparison by people who feel disadvantaged, one way or the other, with people who are at least perceived as privileged. Although privileged people often cannot be held personally responsible for racism and other types of discrimination, there are historically grown structural injustices, which result in some people literally having more chances than others. So gang members are indeed personally responsible for pulling the trigger in acts of violence, but the way society is structured as a whole often hands them the weapons. As for the latter, we all bear some responsibility, if just for our voting habits.

To realize the depth of historically grown structural injustices, it is good to listen to the following speech of Kimberly Jones (be sure to watch the video below of Desiree Barnes against looters to get a complete picture of what this article is all about). Jones ends her powerful statement by saying “They are lucky that as black people what we are looking for is equality and not revenge…”:

White Privilege Forgotten by the Left

While the political right often remains blind to instances of deeply ingrained, historically grown systemic violence and social oppression, the political left often does not want to hear about individual freedom and responsibility. Since on many issues I tend to belong to a community of “white liberals” more than to a community of “white conservatives”, I will write in the first-person plural to develop a self-critical reflection. That is not to say I wouldn’t lean to the right as well sometimes. I guess I’m left in the middle.

Anyway, we liberal white folk, we think love for our neighbor should always include a recognition of our neighbor’s potential traumas. Especially in education we should be aware of the violence in its many guises children carry with them. We are all victims, one way or the other, be it of socio-economic circumstances, bullying, verbal and physical abuse, learning disabilities or mental disorders. Although the recognition of that reality is crucial to become a self-responsible person, it becomes a danger when it is used to simply excuse children for not taking part in the educational process as they should.

There is a significant difference in approaching children as being somewhat determined by their problems or as being free to learn despite their problems. In other words, there is a difference in approaching children as mere victims or as people with potential (think of the Pygmalion or Rosenthal effect in this regard). Not being demanding is not a sign of love and respect in education. You might become popular and powerful among young people in that way, but in the meantime you deny them the dignity to develop their talents. In fact, you become the double of those severe teachers who are only strict to gain a sense of power as well. It does happen, although perhaps more or less unconsciously, that the question to let a pupil pass during deliberations eventually has more to do with a powerplay between teachers than with the interest of pupils themselves. In any case, children from a privileged background will once again find ways to compensate for voids in their education as a consequence of an all too soft approach, while disadvantaged peers in the same educational situation remain the victims of oppressive circumstances. The political left often forgets that type of privilege. Again some people can afford being spoilt during the educational process, while others can’t.

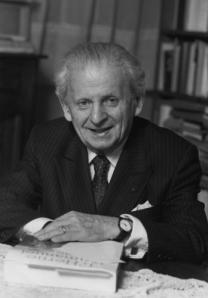

We, white privileged liberals, should be aware of potentially similar dynamics in our assessment of systemic injustices experienced by people of color. Malcolm X (1925-1965) criticized a liberal approach that turns out to simply abuse the victimhood of colored people in a fight over power with white conservatives. He came to the conclusion that many white liberals, consciously or not, have an interest in maintaining that victimhood. Presenting themselves as liberators of a problem they will in fact never solve, those liberals time and again become false Messiahs who gain power and wealth by locking up their followers in an idea of victimhood. In 1963, Malcolm X formulated it this way:

“In this crooked game of power politics here in America, the Negro, namely the race problem, integration and civil rights issues are all nothing but tools, used by the whites who call themselves liberals against another group of whites who call themselves conservatives, either to get into power or to retain power. Among whites here in America, the political teams are no longer divided into Democrats and Republicans. The whites who are now struggling for control of the American political throne are divided into liberal and conservative camps. The white liberals from both parties cross party lines to work together toward the same goal, and white conservatives from both parties do likewise.

The white liberal differs from the white conservative only in one way; the liberal is more deceitful, more hypocritical, than the conservative. Both want power, but the white liberal is the one who has perfected the art of posing as the Negro’s friend and benefactor and by winning the friendship and support of the Negro, the white liberal is able to use the Negro as a pawn or a weapon in this political football game, that is constantly raging between the white liberals and the white conservatives. The American Negro is nothing but a political football.”

For more, listen to:

Against this quite cynical stance of Malcolm X I would argue that the majority of us, white liberals, is genuinely touched by the fate of disadvantaged people, especially oppressed people of color. We feel for them. We sympathize with their just cause to better their socio-economic situation. We are prepared to stand next to them in the fight against racism. Because of the prevalence of drug abuse, poverty and crime in some of their neighborhoods, we understand that it is often very difficult for young black people to fully participate in a good educational process. Hell, we know that some of our own children, growing up in the best of circumstances, wouldn’t take their chances at school if it wasn’t for the high paid tutors to pull them through. Let alone that they would be able to take their chances if they would grow up like some of their disadvantaged black counterparts.

Blaming those black youngsters for their own situation would thus be hypocritical. This is all the more so because the system we receive our privilege from is the same system that keeps them oppressed. Moreover, as privileged white folk we are always partly responsible for maintaining that system and its inherent oppressive violence. That’s why we quite easily refer to socio-economic circumstances when we are confronted with criminal conduct of black youth. We are convinced that at least some of that conduct may be excused, since it is to be partially understood as a consequence of our own violence. And so it happens that by taking up the cause of the disadvantaged fellow citizen, we clear our conscience. We take the moral high ground by judging everything and everyone we perceive as oppressive or racist, while maintaining the same privilege and wealth as them.

Reflexes of the Privileged – The White Conservative in the White Liberal

On the surface we, white liberals, might seem very different from white racists who openly look down on poor and oppressed people of color. However, we don’t really change our white privileged mindset if we merely approach those downtrodden as “helpless victims” who cannot achieve anything without “white” help. At the same time we rave about Steven Pinker’s claim that the world becomes less violent because we rarely ever have to deal with violence directly. We rave about Rutger Bregman’s observation that most people are good until we have to personally deal with those good people doing bad things. In that case we very conveniently refer to the latter as “psychos” – or we use some other convenient monstrous depiction.

The same goes for our attitude towards people we perceive as having a “free spirit”. We rightfully celebrate someone like James Baldwin (1924-1987) as an icon of the Civil Rights Movement and the Gay Liberation Movement. However, we despise the 25 year old gay colleague who falls in love with a 17 year old adolescent. Perhaps this means that we would have only gossiped about James Baldwin if he would have been that colleague, because that is exactly what happened to him at 25.

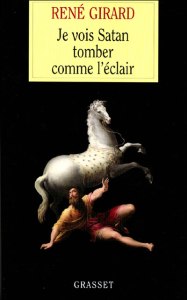

This ambiguous attitude depends on the (physical or mental) distance between ourselves and the others we compare ourselves with. French American thinker René Girard (1923-2015) points out that others can become our heroes in a process of external mediation. This means that others who are somewhat external to our day-to-day life can become models or heroes we admire, and that they mediate some of our ambitions and (secret) dreams.

When those same others become part of the internal circle of our life, however, the dynamic of comparison may turn them into rivals. In a process of internal mediation our models easily become obstacles in the pursuit of our ambitions. They are often perceived as threats to our own position or way of life. That’s why we can stand the free spirited James Baldwin who is far away, and not the same free spirited person who is close by. The latter is often too intimidating. Just his mere presence is already experienced as competing with everything we unwittingly hold dear.

And so we listen to Charlie Parker (1920-1955) and Billie Holiday (1915-1959) in our hipster coffee houses, yet walk around the struggling musician, addicted to heroin, on the way home from work. We pity the poor young man who seems unable to escape a life of crime, yet condemn a poor young man from mixed descent like Diego Maradona, who did become successful and maintained his parents’ family from age 15. We  cuddle the rascal as long as he remains on the streets, but when he rises to the level (or beyond) our privileged situation we tend to look down on him. We actually don’t understand that you can take the man out of the street, but never completely the street out of the man, although we do pay lip service to that sentence. Someone like Maradona is a hero of the poor and the oppressed, first and foremost.

cuddle the rascal as long as he remains on the streets, but when he rises to the level (or beyond) our privileged situation we tend to look down on him. We actually don’t understand that you can take the man out of the street, but never completely the street out of the man, although we do pay lip service to that sentence. Someone like Maradona is a hero of the poor and the oppressed, first and foremost.

The fact that we often feel sympathy for the poor and the oppressed but sometimes look down on their heroes, is a sign of our complacent, paternalistic and condescending supremacy. Maybe we do want to remain saviors, so the problem we want to save people from has to also remain. Disadvantaged communities don’t need this type of false Messiahs. Therefore, we privileged liberals should realize that we often are more concerned with taking down our conservative “enemy” than with actually focusing on the victims of systemic injustices in our institutions. We should truly reflect on the fact and its implications that our lives, spent in the privileged layers of society, have more in common with the lives of our privileged conservative neighbors than with the lives of the disadvantaged. As long as we use movements like Black Lives Matter in a polarized political powerplay that actually drowns the potential for a policy of social reform, we will remain the folk that Malcolm X characterized so sharply.

Taking Matters into Own Hands

On February 14, 2018, 19-year-old Nikolas Cruz shoots 17 people at his former high school in Parkland, Florida. He has already attempted suicide by then. His autism is one of the factors that makes him a target of heavy harassment throughout his youth. His story makes clear that it is not his autism per se that makes him violent to himself and to others, but the social rejection he experiences by bullies, time and again.

On June 2, 2020, a young man shoots David Dorn in front of a pawnshop in St. Louis. David Dorn is a 77-year-old African-American retired police captain. During the social unrest after the police murder of George Floyd, he tries to protect a friend’s pawnshop from looters. It becomes fatal to him. 24-year-old Stephan Cannon is arrested a week later on suspicion of murder.

What Nikolas Cruz and Stephan Cannon have in common is the experience of social rejection. Something like that has similar effects on the brain as physical violence. The former experiences systematic rejection because of his autism, the latter experiences systemic rejection because of his skin color. Both forms of rejection are to be condemned. Unfortunately, neither Cruz nor Cannon seem to experience this condemnation. As a result, they ultimately share another violent reality: they make innocent others, i.e. scapegoats pay for the frustrations they both experience in the course of their lives.

It might be tempting to further isolate perpetrators such as Cruz and Cannon and to explain their violent actions on the basis of a hyper-individual problem from which they would suffer. However, this is all too easy and actually indicates a cowardly attitude. The way communities are made up does play a role in the way individuals behave. In other words, each community has a share and a responsibility in the violence perpetrated by some individuals. Again, a social environment might not pull the trigger, but it often does hand the weapons (see above). This is not to say that perpetrators of violence themselves bear no overwhelming responsibility. Cruz and Cannon do have a freedom of choice. In the end, they pull the trigger – or not.

It is important that Black Lives Matter acknowledges that someone like Stephan Cannon is also one of those blacks who feel rejected in a society dominated by white privilege. Stephan Cannon’s violence, as a revenge against the violence of social discrimination, is an actual imitation and continuation of white supremacy violence. It is precisely for this reason that Black Lives Matter, in addition to making an analysis of the causes of revenge against innocent third parties, must also clearly condemn this form of violence. If it doesn’t, it puts that condemnation in the hands of its opponents. The latter can then continue to live with the illusion that they have nothing to do with the frustrations of a young criminal. In that case, a society dominated by white privilege remains blind to its own violence. The condemnation of violence is therefore not a side issue in the struggles of movements such as Black Lives Matter. It belongs to their essence, at least if they don’t want to become part of the violent hatred they thought they were opposing.

So it is important that protesters against injustices listen to people like Desiree Barnes (a former Obama aide, by the way):

Malcolm X did not advocate violence as a necessary means to solve the problem of racial injustices. Following Malcolm X, oppressed people of color are not helped by an approach that turns perpetrators of violence from their communities into mere victims of other violence. It only turns those communities as a whole into the poor victims privileged liberals paternalistically love to use in their rivalry over power against privileged conservatives. Again, if movements like Black Lives Matter do not condemn violence against innocent bystanders, those conservatives will easily put the blame for violence on the side of protesters and remain blind to the reality of systemic violent oppression.

In short, following Malcolm X and other African-American voices on the matter at hand, black people in America should not look at themselves through the eyes of some of the white conservatives or white liberals, who often treat them as criminals or victims respectively. They should look at themselves as people with the potential to create a more just society, who can take matters into their own hands, and who can become agents of change.

In de loop der jaren heb ik heel wat materiaal verzameld waarnaar expliciet in de documentaire-reeks

In de loop der jaren heb ik heel wat materiaal verzameld waarnaar expliciet in de documentaire-reeks  Elke emancipatorische beweging moet zich afvragen in welke mate ze werkelijk emancipatorisch is. Wil de

Elke emancipatorische beweging moet zich afvragen in welke mate ze werkelijk emancipatorisch is. Wil de  Het is dus goed dat een beweging als Black Lives Matter ook zogenaamd “dissidente stemmen” uit de eigen, zwarte gemeenschap beluistert. Op die manier wordt ze niet de zoveelste beweging in de geschiedenis van de mensheid die eigenlijk het kwaad in stand houdt dat ze dacht te bestrijden omdat ze haar eigen (fysiek en ander) geweld beschouwt als “goed en gerechtvaardigd”. Het boek Virtuous Violence, dat in de eerste aflevering van Why We Hate te zien is op de tafel van Brian Hare, beschrijft dat proces (zie

Het is dus goed dat een beweging als Black Lives Matter ook zogenaamd “dissidente stemmen” uit de eigen, zwarte gemeenschap beluistert. Op die manier wordt ze niet de zoveelste beweging in de geschiedenis van de mensheid die eigenlijk het kwaad in stand houdt dat ze dacht te bestrijden omdat ze haar eigen (fysiek en ander) geweld beschouwt als “goed en gerechtvaardigd”. Het boek Virtuous Violence, dat in de eerste aflevering van Why We Hate te zien is op de tafel van Brian Hare, beschrijft dat proces (zie

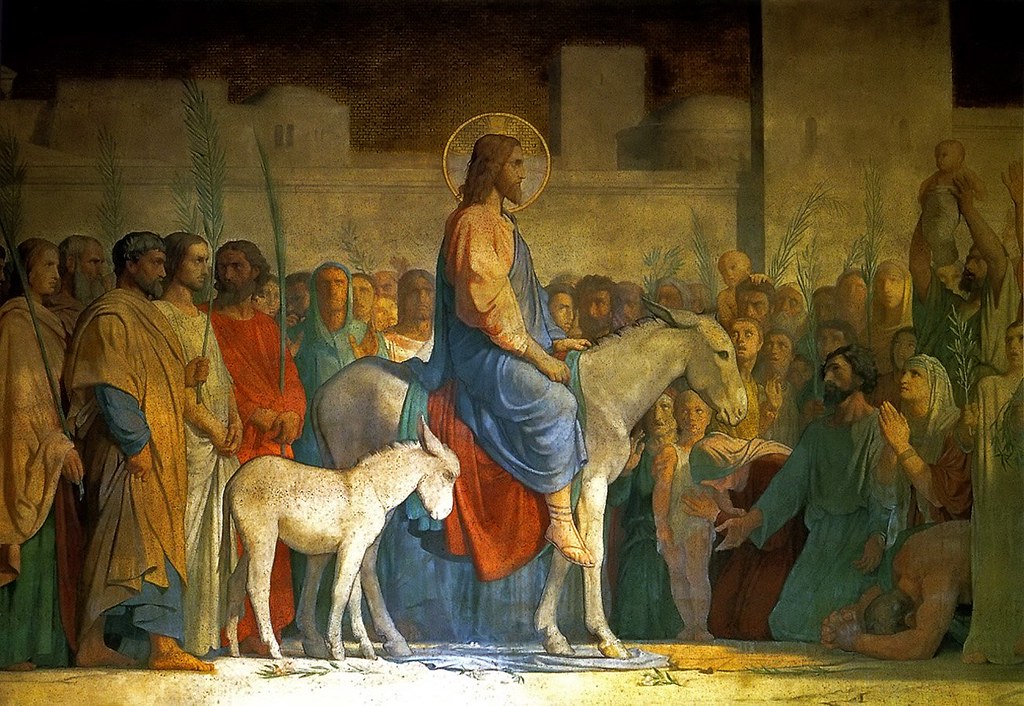

Humans commit transgressions of god given laws. The gods get angry. Disasters happen as divine punishment. Humans bring sacrifices which reconcile them with the gods. Peace is restored.

Humans commit transgressions of god given laws. The gods get angry. Disasters happen as divine punishment. Humans bring sacrifices which reconcile them with the gods. Peace is restored. If we are to believe this account, then the God of Christ is a hero of unmatched mythical proportions. He saves others from the deadly disasters He Himself would be responsible for by provisionally killing Himself as the potential presence of wrathful violence in the sacrifice of his Son. In other words, from this perspective the God of Christ is a force of violence that controls itself and others by violent sacrificial means. The peace of Christ is the violent peace of sterile uniformity, established by sacrifice.

If we are to believe this account, then the God of Christ is a hero of unmatched mythical proportions. He saves others from the deadly disasters He Himself would be responsible for by provisionally killing Himself as the potential presence of wrathful violence in the sacrifice of his Son. In other words, from this perspective the God of Christ is a force of violence that controls itself and others by violent sacrificial means. The peace of Christ is the violent peace of sterile uniformity, established by sacrifice.  The Gospel reveals that we, humans, tend to be guided by the scapegoat mechanism. Instead of acknowledging our freedom and creative strength as human beings to deal responsibly with disasters, we tend to look for the so-called “masterminds” behind the crisis situations we encounter. Conspiracy theories are the secularized version of traditional religious and mythical thinking. They provide us with a false sense of security and the delusional entitlement to sacrifice so-called “evil” others, who are believed to be responsible for the crisis at hand in the first place. In the case of a pandemic like COVID-19, some keep believing there is a God who punishes us for allowing evildoers in our midst, while others believe powerful people developed a plot that involves deliberately spreading a virus on their path to world dominion.

The Gospel reveals that we, humans, tend to be guided by the scapegoat mechanism. Instead of acknowledging our freedom and creative strength as human beings to deal responsibly with disasters, we tend to look for the so-called “masterminds” behind the crisis situations we encounter. Conspiracy theories are the secularized version of traditional religious and mythical thinking. They provide us with a false sense of security and the delusional entitlement to sacrifice so-called “evil” others, who are believed to be responsible for the crisis at hand in the first place. In the case of a pandemic like COVID-19, some keep believing there is a God who punishes us for allowing evildoers in our midst, while others believe powerful people developed a plot that involves deliberately spreading a virus on their path to world dominion. “By nailing Christ to the Cross, the powers believed they were doing what they ordinarily did in unleashing the single victim mechanism. They thought they were avoiding the danger of disclosure. They did not suspect that in the end they would be doing just the opposite: they would be contributing to their own annihilation, nailing themselves to the Cross, so to speak. They did not and could not suspect the revelatory power of the Cross. […] The powers are not put on display because they are defeated, but they are defeated because they are put on display.”

“By nailing Christ to the Cross, the powers believed they were doing what they ordinarily did in unleashing the single victim mechanism. They thought they were avoiding the danger of disclosure. They did not suspect that in the end they would be doing just the opposite: they would be contributing to their own annihilation, nailing themselves to the Cross, so to speak. They did not and could not suspect the revelatory power of the Cross. […] The powers are not put on display because they are defeated, but they are defeated because they are put on display.”

“gebrainwasht” na jaren werken op het Sint-Jozefscollege, door de jezuïeten en de spiritualiteit van hun stichter, Ignatius van Loyola (1491-1556).

“gebrainwasht” na jaren werken op het Sint-Jozefscollege, door de jezuïeten en de spiritualiteit van hun stichter, Ignatius van Loyola (1491-1556). Ik twijfel vrij geregeld aan mijn geloof in God. Net zoals atheïsten die filosofisch zijn aangelegd ook wel eens aan hun ongeloof zullen twijfelen. (Niet) geloven is immers iets anders dan weten.

Ik twijfel vrij geregeld aan mijn geloof in God. Net zoals atheïsten die filosofisch zijn aangelegd ook wel eens aan hun ongeloof zullen twijfelen. (Niet) geloven is immers iets anders dan weten. Het voordeel van een beroepsopleiding is alvast dat leerlingen zichzelf en de wereld uiteindelijk moeilijk iets kunnen voorliegen: een gemetste muur is recht en blijft overeind, of ze is slecht gemetst. Leerlingen in het algemeen secundair onderwijs kunnen zichzelf langer op het verkeerde been zetten. Ze kunnen wiskundige bewijzen “van buiten” leren zonder die te begrijpen bijvoorbeeld, of vertalingen van Latijn en formules van fysica. De Einsteins van deze wereld studeren echter niet om de punten of het geld. Ze ontplooien een gepassioneerde liefde voor de werkelijkheid die ze willen leren kennen.

Het voordeel van een beroepsopleiding is alvast dat leerlingen zichzelf en de wereld uiteindelijk moeilijk iets kunnen voorliegen: een gemetste muur is recht en blijft overeind, of ze is slecht gemetst. Leerlingen in het algemeen secundair onderwijs kunnen zichzelf langer op het verkeerde been zetten. Ze kunnen wiskundige bewijzen “van buiten” leren zonder die te begrijpen bijvoorbeeld, of vertalingen van Latijn en formules van fysica. De Einsteins van deze wereld studeren echter niet om de punten of het geld. Ze ontplooien een gepassioneerde liefde voor de werkelijkheid die ze willen leren kennen. De reden waarom een katholieke spiritualiteit in navolging van Christus hamert op een realistische zelfaanvaarding, zelfliefde, zelfontplooiing en ja, een altijd zéér betrekkelijke “zelfbeschikking”, is eenvoudig: ze is de basisvoorwaarde om “God” (zijnde liefde) toe te laten in je leven. Zelfrespect leidt tot respect voor anderen. De alcoholverslaafde die zichzelf niet langer kan respecteren, kan op den duur ook geen verantwoordelijkheid meer opnemen voor anderen. De bouwkundige ingenieur die op een frauduleuze manier zijn diploma behaalt, zal misschien bruggen bouwen die in elkaar storten en slachtoffers veroorzaken.

De reden waarom een katholieke spiritualiteit in navolging van Christus hamert op een realistische zelfaanvaarding, zelfliefde, zelfontplooiing en ja, een altijd zéér betrekkelijke “zelfbeschikking”, is eenvoudig: ze is de basisvoorwaarde om “God” (zijnde liefde) toe te laten in je leven. Zelfrespect leidt tot respect voor anderen. De alcoholverslaafde die zichzelf niet langer kan respecteren, kan op den duur ook geen verantwoordelijkheid meer opnemen voor anderen. De bouwkundige ingenieur die op een frauduleuze manier zijn diploma behaalt, zal misschien bruggen bouwen die in elkaar storten en slachtoffers veroorzaken.

And the child who is used to be treated as a superior being might think he indeed is superior to others and might only listen to people who confirm his self-concept. This child does not know who he is or what his qualities are, apart from being the narcissist he has become. He has difficulty recognizing his own flaws. Being ashamed of himself in this way, he tends to look down on others – as if he is flawless and they are full of mistakes.

And the child who is used to be treated as a superior being might think he indeed is superior to others and might only listen to people who confirm his self-concept. This child does not know who he is or what his qualities are, apart from being the narcissist he has become. He has difficulty recognizing his own flaws. Being ashamed of himself in this way, he tends to look down on others – as if he is flawless and they are full of mistakes.

Someone who suffers from an inferiority complex has the tendency to idolize others and to blame himself for everything that goes wrong in his life. He also has the tendency to compare himself to those so-called “perfect” others in order to develop an acceptable self-image. Thus he is primarily interested in others as “mirrors”. Others are reduced to means who should confirm a certain self-image. Having experienced a lack of love while growing up, the person who suffers from an inferiority complex is not interested in himself apart from the image he hopes will give him some social recognition. Unable to truly respect himself he is also unable to respect others. As said, he is only interested in them as means, not as ends in themselves. His whole life is dominated by fear, more specifically by the fear of punishment or rejection by others if he doesn’t live up to a so-called acceptable image in his main social environment. His life is hell. Hell is real. 1 John 4:18 puts it this way:

Someone who suffers from an inferiority complex has the tendency to idolize others and to blame himself for everything that goes wrong in his life. He also has the tendency to compare himself to those so-called “perfect” others in order to develop an acceptable self-image. Thus he is primarily interested in others as “mirrors”. Others are reduced to means who should confirm a certain self-image. Having experienced a lack of love while growing up, the person who suffers from an inferiority complex is not interested in himself apart from the image he hopes will give him some social recognition. Unable to truly respect himself he is also unable to respect others. As said, he is only interested in them as means, not as ends in themselves. His whole life is dominated by fear, more specifically by the fear of punishment or rejection by others if he doesn’t live up to a so-called acceptable image in his main social environment. His life is hell. Hell is real. 1 John 4:18 puts it this way:

As Irenaeus of Lyons (130-202) writes, “the glory of God is the human person fully alive.” The human person who is “fully alive” is the person who overcomes fear in order to love more deeply. Love transforms fear from fear of the other (as a potential rival) into fear for the other (as my neighbor).

As Irenaeus of Lyons (130-202) writes, “the glory of God is the human person fully alive.” The human person who is “fully alive” is the person who overcomes fear in order to love more deeply. Love transforms fear from fear of the other (as a potential rival) into fear for the other (as my neighbor). Yes.

Yes.

Several lines of evidence indicate some female competition over mating. First, at Mahale, females sometimes directly interfered in the mating attempts of their rivals by forcing themselves between a copulating pair. In some cases, the aggressive female went on to mate with the male. At Gombe, during a day-long series of attacks by Mitumba females on a fully swollen new immigrant female, the most active attackers were also swollen and their behaviour was interpreted as ‘sexual jealousy’ by the observers. Townsend et al. found that females at Budongo suppressed copulation calls when in the presence of the dominant female, possibly to prevent direct interference in their copulations. Second, females occasionally seem to respond to the sexual swellings of others by swelling themselves. Goodall described an unusual incident in which a dominant, lactating female suddenly appeared with a full swelling a day after a young oestrous female had been followed by many males. Nishida described cases at Mahale in which a female would produce isolated swellings that were not part of her regular cycles when a second oestrous female was present in the group.

Several lines of evidence indicate some female competition over mating. First, at Mahale, females sometimes directly interfered in the mating attempts of their rivals by forcing themselves between a copulating pair. In some cases, the aggressive female went on to mate with the male. At Gombe, during a day-long series of attacks by Mitumba females on a fully swollen new immigrant female, the most active attackers were also swollen and their behaviour was interpreted as ‘sexual jealousy’ by the observers. Townsend et al. found that females at Budongo suppressed copulation calls when in the presence of the dominant female, possibly to prevent direct interference in their copulations. Second, females occasionally seem to respond to the sexual swellings of others by swelling themselves. Goodall described an unusual incident in which a dominant, lactating female suddenly appeared with a full swelling a day after a young oestrous female had been followed by many males. Nishida described cases at Mahale in which a female would produce isolated swellings that were not part of her regular cycles when a second oestrous female was present in the group.