As a kid, René Magritte used to play at an abandoned cemetery, together with a little girl. He saw a painter there, who seemed to him to possess magical powers… (thanks to Marcel Paquet’s Taschen book, for this and the following information on Magritte).

Of course, later on, Magritte (1898-1967) became a painter himself, and an intriguing one. The Belgian surrealist managed to create a world of ideas and suggestions on the canvas. As it turns out, many of his paintings drew from the experiences he had at the cemetery of his childhood. His surreal work contains a world of opposites: a heavy rock is painted as a levitating object, a nocturnal landscape is depicted under a blue, white clouded and sunlit sky… These and other examples remind of the contrasting experiences Magritte underwent at the cemetery: the promising life of two young children contrasts with a place of dead, decaying bodies, as the first hints of a sensual interplay between a boy and a girl contrast with the barrenness of the graveyard surroundings. At the same time, Magritte’s paintings convey the paradoxes of any artist’s ‘magical’ creativity: at once all-powerful and powerless. Indeed, a painter is able to create a world according to his own laws (levitating rocks, for example), yet he never manages to capture reality itself. The Treachery of Images (French: La trahison des images; 1928-1929), Magritte’s well-known painting of a pipe, makes this clear. The subscript Ceci n’est pas une pipe shows the idea that we only access reality through images, representations, or indeed, mimesis. The image of a pipe is not the pipe itself. A poetic equivalent could be the expression ‘I’m speechless’. For saying ‘I’m speechless’ actually implies speaking, so the reality of being speechless is misrepresented by the expression itself. The Italian movie La vita è bella (Roberto Benigni, 1997) contains a riddle in a similar sense: “When you say my name, I’m gone… Who am I? Answer: ‘Silence’…”

Of course, later on, Magritte (1898-1967) became a painter himself, and an intriguing one. The Belgian surrealist managed to create a world of ideas and suggestions on the canvas. As it turns out, many of his paintings drew from the experiences he had at the cemetery of his childhood. His surreal work contains a world of opposites: a heavy rock is painted as a levitating object, a nocturnal landscape is depicted under a blue, white clouded and sunlit sky… These and other examples remind of the contrasting experiences Magritte underwent at the cemetery: the promising life of two young children contrasts with a place of dead, decaying bodies, as the first hints of a sensual interplay between a boy and a girl contrast with the barrenness of the graveyard surroundings. At the same time, Magritte’s paintings convey the paradoxes of any artist’s ‘magical’ creativity: at once all-powerful and powerless. Indeed, a painter is able to create a world according to his own laws (levitating rocks, for example), yet he never manages to capture reality itself. The Treachery of Images (French: La trahison des images; 1928-1929), Magritte’s well-known painting of a pipe, makes this clear. The subscript Ceci n’est pas une pipe shows the idea that we only access reality through images, representations, or indeed, mimesis. The image of a pipe is not the pipe itself. A poetic equivalent could be the expression ‘I’m speechless’. For saying ‘I’m speechless’ actually implies speaking, so the reality of being speechless is misrepresented by the expression itself. The Italian movie La vita è bella (Roberto Benigni, 1997) contains a riddle in a similar sense: “When you say my name, I’m gone… Who am I? Answer: ‘Silence’…”

Medieval thinkers were very much aware of these paradoxes and of the mediated nature of all human knowledge. Reality, which was ultimately divine to them, is always bigger and ‘different’ than our representations of it. We live by symbols and images, referring to ‘what lies beyond’ them. Somehow we seem to lose this awareness more and more. We seem to lose ourselves to the impression we can control many aspects of our own life, and many aspects – if not all – of ‘reality’. We live in a world where everything is said to be ‘manageable’, a world of plans and strategies, of ideologies and calculations – calculated ‘risks’ and false certainties. We think we can master reality, that we are free and independent ‘Masters of the Universe’, yet the background radiation of our day-to-day conscience tells a different story: climate change gets at us in unexpected ways, terrorist attacks stun us time and again, and accidents ‘do happen’.

I just finished reading The Book of Illusions, a novel by Paul Auster. He’s on my list of favorites already (next to Milan Kundera and John Maxwell Coetzee – who are, as I discovered after I’d read them, both admirers of René Girard’s work –, and next to the not so well-known Craig Strete). I loved reading the story because of its surreal feel, because it breathes both the anguish and hope that ‘nothing is what it seems’. The story is carried by the character of a David Zimmer, a Vermont professor who lost his wife and two young sons in a plane crash. As fate would have it, he delves into the life of the mysterious silent comedian and film director Hector Mann. Writing the story of Mann’s life and films somehow saves Zimmer’s life from despair. As it turns out, there are some remarkable analogies between the two men. In some ways, the life of Zimmer is an imitation of Mann’s life. Moreover, one of Mann’s later films, The Inner Life of Martin Frost, represents an important aspect of Mann’s own life. So we have one imitation after the other. As a whole, Auster’s novel reflects aspects of our own ‘condition’. We are mimetic creatures, we live by ‘representations’ of ourselves and of reality as a whole. We construct our own ‘story’. Yet life is not a story. Louis Paul Boon (1912-1979), a famous Flemish writer, honorary citizen of my hometown Aalst, conveyed this insight in a great way. A book has a beginning and an end, while we don’t actually know when ‘we’ begin, nor can plan when we catch a deadly disease or undergo a life threatening accident. Our lives are ‘open endings’, fractures, interrupted beyond our control by unplanned experiences. Paul Auster seems to also make clear that in order to give life a chance, an author must be prepared to ‘burn’ his own work. He has to ‘question mark’ it. The chapter on The Inner Life of Martin Frost, the one late movie of Hector Mann watched by Zimmer, magnificently reflects this indeed ‘surreal’ and ‘poetic’ idea. The movie is about the muse of writer Martin Frost. Claire Martin, as she calls herself, is slowly dying while he finishes his story. In order to bring her back to life, Frost burns his story, thereby expressing the irreducibility of any human being’s character. He understands that capturing someone else’s life in a well-defined story (with beginning and ending) actually ‘kills’ this person in a way. Writing about Claire is also stating ‘this is not Claire’. Here’s the fragment:

Martin shakes out three aspirins from the bottle and hands them to her with a glass of water. As Claire swallows the pills, Martin says: This isn’t good. I really think a doctor should take a look at you.

Claire gives Martin the empty glass, and he puts it back on the table. Tell me what’s happening in the story, she says. That will make me feel better.

You should rest.

Please, Martin. Just a little bit.

Not wanting to disappoint her, and yet not wanting to tax her strength, Martin confines his summary to just a few sentences. It’s dark now, he says. Nordstrum has left the house. Anna is on her way, but he doesn’t know that. If she doesn’t get there soon, he’s going to walk into the trap.

Will she make it?

It doesn’t matter. The important thing is that she’s going to him.

She’s fallen in love with him, hasn’t she?

In her own way, yes. She’s putting her life in danger for him. That’s a form of love, isn’t it?

Claire doesn’t answer. Martin’s question has overwhelmed her, and she is too moved to give a response. Her eyes fill up with tears; her mouth trembles; a look of rapturous intensity shines forth from her face. It’s as if she has reached some new understanding of herself, as if her whole body were suddenly giving off light. How much more to go? she asks.

Two or three pages, Martin says. I’m almost at the end.

Write them now.

They can wait. I’ll do them tomorrow.

No, Martin, do them now. You must do them now.

The camera lingers on Claire’s face for a moment or two– and then, as if propelled by the force of her command, Martin cuts between the two characters. We go from Martin back to Claire, from Claire back to Martin, and in the space of ten simple shots, we finally get it, we finally understand what’s been happening. Then Martin returns to the bedroom, and in ten more shots he finally understands as well.

1. Claire is writhing around on the bed, in acute pain, struggling not to call out for help.

2. Martin comes to the bottom of a page, pulls it out of the machine, and rolls in another. He begins typing again.

3. We see the fireplace. The fire has nearly gone out.

4. A close-up of Martin’s fingers, typing.

5. A close-up of Claire’s face. She is weaker than before, no longer struggling.

6. A close-up of Martin’s face. At his desk, typing.

7. A close-up of the fireplace. Just a few glowing embers.

8. A medium shot of Martin. He types the last word of his story. A brief pause. Then he pulls the page out of the machine.

9. A medium shot of Claire. She shudders slightly–and then appears to die.

10. Martin is standing beside his desk, gathering up the pages of the manuscript. He walks out of the study, holding the finished story in his hand.

11. Martin enters the room, smiling. He glances at the bed, and an instant later the smile is gone.

12. A medium shot of Claire. Martin sits down beside her, puts his hand on her forehead, and gets no response. He presses his ear against her chest–still no response. In a mounting panic, he tosses aside the manuscript and begins rubbing her body with both hands, desperately trying to warm her up. She is limp; her skin is cold; she has stopped breathing.

13. A shot of the fireplace. We see the dying embers. There are no more logs on the hearth.

14. Martin jumps off the bed. Snatching the manuscript as he goes, he wheels around and rushes toward the fireplace. He looks possessed, out of his mind with fear. There is only one thing left to be done–and it must be done now. Without hesitation, Martin crumples up the first page of his story and throws it into the fire.

15. A close-up of the fire. The ball of paper lands in the ashes and bursts into flame. We hear Martin crumpling up another page. A moment later, the second ball lands in the ashes and ignites.

16. Cut to a close-up of Claire’s face. Her eyelids begin to flutter.

17. A medium shot of Martin, crouched in front of the fire. He grabs hold of the next sheet, crumples it up, and throws it in as well. Another sudden burst of flame.

18. Claire opens her eyes.

19. Working as fast as he can now, Martin goes on bunching up pages and throwing them into the fire. One by one, they all begin to burn, each one lighting the other as the flames intensify.

20. Claire sits up. Blinking in confusion; yawning; stretching out her arms; showing no traces of illness. She has been brought back from the dead.

Gradually coming to her senses, Claire begins to glance around the room, and when she sees Martin in front of the fireplace, madly crumpling up his manuscript and throwing it into the fire, she looks stricken. What are you doing? she says. My God, Martin, what are you doing?

I’m buying you back, he says. Thirty-seven pages for your life, Claire. It’s the best bargain I’ve ever made.

But you can’t do that. It’s not allowed.

Maybe not. But I’m doing it, aren’t I? I’ve changed the rules.

Claire is overwrought, about to break down in tears. Oh Martin, she says. You don’t know what you’ve done.

Undaunted by Claire’s objections, Martin goes on feeding his story to the flames. When he comes to the last page, he turns to her with a triumphant look in his eyes. You see, Claire? he says. It’s only words. Thirty-seven pages–and nothing but words.

He sits down on the bed, and Claire throws her arms around him. It is a surprisingly fierce and passionate gesture, and for the first time since the beginning of the film, Claire looks afraid. She wants him, and she doesn’t want him. She is ecstatic; she is horrified. She has always been the strong one, the one with all the courage and confidence, but now that Martin has solved the riddle of his enchantment, she seems lost. What are you going to do? she says. Tell me, Martin, what on earth are we going to do?

Before Martin can answer her, the scene shifts to the outside. We see the house from a distance of about fifty feet, sitting in the middle of nowhere. The camera tilts upward, pans to the right, and comes to rest on the boughs of a large cottonwood. Everything is still. No wind is blowing; no air is rushing through the branches; not a single leaf moves. Ten seconds go by, fifteen seconds go by, and then, very abruptly, the screen goes black and the film is over.

(Taken from Paul Auster, The Book of Illusions, Faber and Faber open market edition, 2003, p.265-269).

As a Phoenix rising from her ashes, Claire breathes new life into Martin Frost’s existence, melting away his ‘frost’, taking him away from the reflections in his books to the tangible reality of her ‘body’ – born, nevertheless, from the sparks of his imagination… Spicy, ‘mimetic’ detail: as Claire (‘the brightness’) was willing to sacrifice herself to let Martin’s story come alive, Hector was willing to sacrifice himself to save… well, you’ll have to read the book to know ;-).

Paul Auster’s is a story of the paradoxical power of art, storytelling and human communication in general. In order to ‘experience’ reality, we cannot but refer to it by ‘duplicating’ or ‘imitating’ it. As this is also a ‘treason’ of reality it’s exactly what ‘saves’ it at the same time. For that which we ‘possess’ in words, images and gestures is not reality ‘itself’, reality remains ‘untouched’ and ‘unspoiled’ in a way. It’s what lies ‘beyond’, as that sublime, ungraspable mystery…

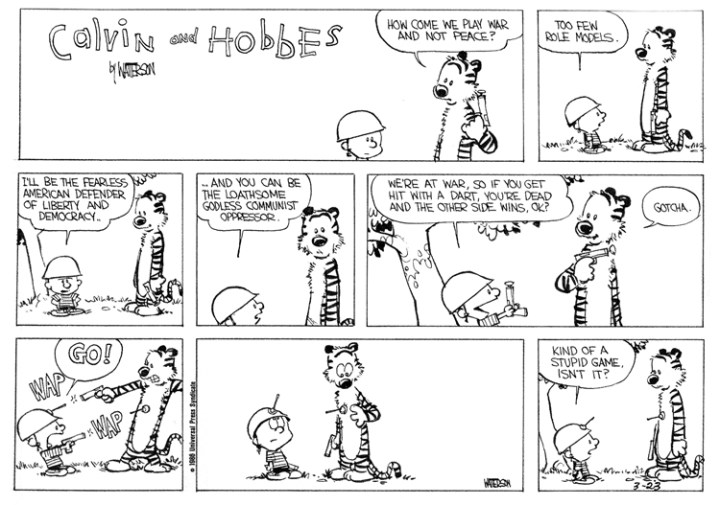

While reading the book, I couldn’t help but imagine the films of one of my favorite directors, namely Billy Wilder (1906-2002). In more than one way, the story of Hector Mann in Auster’s book reminded me of the story in Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard. I also had to think, surprisingly perhaps, of another kind of moviemaking. I was reminded of a video-clip by Norwegian pop-band a-ha, for their big hit song ‘Take on Me’. 25 years after the song earned six awards at the 1986 MTV Video Music Awards (September 5, 1986), I’d like to celebrate the art and craftsmanship of the video once more. Like Paul Auster refers to moviemaking in his novel, a-ha made a video-clip with references to yet another art-form, comics. Scott McCloud points to the distinction between animation and comics in his truly inspiring book Understanding Comics – The Invisible Art: “Each successive frame of a movie is projected on exactly the same space – the screen – while each frame of comics must occupy a different space. Space does for comics what time does for film!” Makes one think about the mysteries of space and time, and our vain attempts to grasp them…

While reading the book, I couldn’t help but imagine the films of one of my favorite directors, namely Billy Wilder (1906-2002). In more than one way, the story of Hector Mann in Auster’s book reminded me of the story in Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard. I also had to think, surprisingly perhaps, of another kind of moviemaking. I was reminded of a video-clip by Norwegian pop-band a-ha, for their big hit song ‘Take on Me’. 25 years after the song earned six awards at the 1986 MTV Video Music Awards (September 5, 1986), I’d like to celebrate the art and craftsmanship of the video once more. Like Paul Auster refers to moviemaking in his novel, a-ha made a video-clip with references to yet another art-form, comics. Scott McCloud points to the distinction between animation and comics in his truly inspiring book Understanding Comics – The Invisible Art: “Each successive frame of a movie is projected on exactly the same space – the screen – while each frame of comics must occupy a different space. Space does for comics what time does for film!” Makes one think about the mysteries of space and time, and our vain attempts to grasp them…

Well, what kind of storytelling you prefer, doesn’t really matter. However, I’m strongly convinced that what we need today is the art of storytelling. Too many tragedies seem to happen nowadays because of people who live from ‘indisputable ideologies’ (stories turned frigid) – the Norwegian had their tragedy, the world as a whole had 9/11. To write the story to let others come alive, while also realizing that ‘the other’ is always bigger than ‘our story’ – that’s what we need… “In the beginning was the Word…” (John 1:1). The Word between one man and the other, the Poet creating proximity and distance at the same time, creating tenderness… Like a painter, who caresses the image of his beloved model with a paintbrush, leaving the model herself ‘untouched’…

Well, what kind of storytelling you prefer, doesn’t really matter. However, I’m strongly convinced that what we need today is the art of storytelling. Too many tragedies seem to happen nowadays because of people who live from ‘indisputable ideologies’ (stories turned frigid) – the Norwegian had their tragedy, the world as a whole had 9/11. To write the story to let others come alive, while also realizing that ‘the other’ is always bigger than ‘our story’ – that’s what we need… “In the beginning was the Word…” (John 1:1). The Word between one man and the other, the Poet creating proximity and distance at the same time, creating tenderness… Like a painter, who caresses the image of his beloved model with a paintbrush, leaving the model herself ‘untouched’…

‘She’ is always the one who saves us from ‘the labyrinth’ – from the dark cave of the womb into the light. ‘She’ is reality beyond our words and imaginations, beyond the games we play, beyond virtual competitions where we try to find a sense of ‘victory’, beyond the illusion that we are ‘masters’ of reality. Life is not a programmed, predestined computer game (Tron, the movie, anyone?).

Enjoy ‘Take on Me’… and the life bringers. Click to watch a pop defining moment – ‘mirror, mirror…’ indeed:

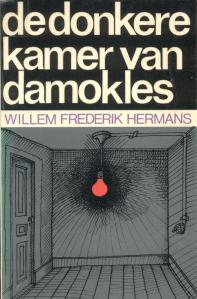

De brief is gebaseerd op een proefschrift van Sonja Pos. Over haar benadering van De donkere kamer van Damokles schreef W.F. Hermans aan een vriend: “Sommige beschouwingen over mijn werk kan ik niet lezen zonder angstgevoelens. Ken jij: Mimese en geweld, beschouwingen over het werk van René Girard, Kampen 1988? Hierin staat een opstel van Sonja Pos over De donkere kamer van Damokles, dat me bang van mijzelf liet worden toen ik het las. Nou ja, ik overdrijf een beetje. Het is een van de beste beschouwingen die er ooit over dat veelbesproken verhaal zijn verschenen.”

De brief is gebaseerd op een proefschrift van Sonja Pos. Over haar benadering van De donkere kamer van Damokles schreef W.F. Hermans aan een vriend: “Sommige beschouwingen over mijn werk kan ik niet lezen zonder angstgevoelens. Ken jij: Mimese en geweld, beschouwingen over het werk van René Girard, Kampen 1988? Hierin staat een opstel van Sonja Pos over De donkere kamer van Damokles, dat me bang van mijzelf liet worden toen ik het las. Nou ja, ik overdrijf een beetje. Het is een van de beste beschouwingen die er ooit over dat veelbesproken verhaal zijn verschenen.” Hermans’ enthousiasme doet denken aan een bewering van een andere grote romancier, Milan Kundera. Deze Tsjechisch-Franse auteur schreef over het eerste boek van Girard: “Mensonge romantique et vérité romanesque is het beste dat ik ooit over de romankunst heb gelezen.” (uit Verraden Testamenten, Baarn, Ambo, 1994, p.160).

Hermans’ enthousiasme doet denken aan een bewering van een andere grote romancier, Milan Kundera. Deze Tsjechisch-Franse auteur schreef over het eerste boek van Girard: “Mensonge romantique et vérité romanesque is het beste dat ik ooit over de romankunst heb gelezen.” (uit Verraden Testamenten, Baarn, Ambo, 1994, p.160). René Girard beschreef in De romantische leugen en de romaneske waarheid Europese literatuur waarin de hoofdpersonen een model navolgen. Soms zijn dat geen daadwerkelijke personages, maar verre geïdealiseerde voorbeelden zoals in Don Quichot van Cervantes. Deze relatie is eenzijdig: de hoofdpersoon oefent geen invloed uit op het model. Maar wat als het model dat door de hoofdpersoon van een roman wordt nagevolgd, niet veraf maar dichtbij is? Dan kan er rivaliteit ontstaan waarbij het model een obstakel voor de navolger gaat vormen, een voorwerp van haat. De mimetische rivaliteit is volgens Girard niet alleen besmettelijk maar ook destructief.

René Girard beschreef in De romantische leugen en de romaneske waarheid Europese literatuur waarin de hoofdpersonen een model navolgen. Soms zijn dat geen daadwerkelijke personages, maar verre geïdealiseerde voorbeelden zoals in Don Quichot van Cervantes. Deze relatie is eenzijdig: de hoofdpersoon oefent geen invloed uit op het model. Maar wat als het model dat door de hoofdpersoon van een roman wordt nagevolgd, niet veraf maar dichtbij is? Dan kan er rivaliteit ontstaan waarbij het model een obstakel voor de navolger gaat vormen, een voorwerp van haat. De mimetische rivaliteit is volgens Girard niet alleen besmettelijk maar ook destructief.

While reading the book, I couldn’t help but imagine the films of one of my favorite directors, namely Billy Wilder (1906-2002). In more than one way, the story of Hector Mann in Auster’s book reminded me of the story in Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard. I also had to think, surprisingly perhaps, of another kind of moviemaking. I was reminded of a video-clip by Norwegian pop-band a-ha, for their big hit song ‘Take on Me’. 25 years after the song earned six awards at the 1986 MTV Video Music Awards (September 5, 1986), I’d like to celebrate the art and craftsmanship of the video once more. Like Paul Auster refers to moviemaking in his novel, a-ha made a video-clip with references to yet another art-form, comics. Scott McCloud points to the distinction between animation and comics in his truly inspiring book Understanding Comics – The Invisible Art: “Each successive frame of a movie is projected on exactly the same space – the screen – while each frame of comics must occupy a different space. Space does for comics what time does for film!” Makes one think about the mysteries of space and time, and our vain attempts to grasp them…

While reading the book, I couldn’t help but imagine the films of one of my favorite directors, namely Billy Wilder (1906-2002). In more than one way, the story of Hector Mann in Auster’s book reminded me of the story in Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard. I also had to think, surprisingly perhaps, of another kind of moviemaking. I was reminded of a video-clip by Norwegian pop-band a-ha, for their big hit song ‘Take on Me’. 25 years after the song earned six awards at the 1986 MTV Video Music Awards (September 5, 1986), I’d like to celebrate the art and craftsmanship of the video once more. Like Paul Auster refers to moviemaking in his novel, a-ha made a video-clip with references to yet another art-form, comics. Scott McCloud points to the distinction between animation and comics in his truly inspiring book Understanding Comics – The Invisible Art: “Each successive frame of a movie is projected on exactly the same space – the screen – while each frame of comics must occupy a different space. Space does for comics what time does for film!” Makes one think about the mysteries of space and time, and our vain attempts to grasp them… Well, what kind of storytelling you prefer, doesn’t really matter. However, I’m strongly convinced that what we need today is the art of storytelling. Too many tragedies seem to happen nowadays because of people who live from ‘indisputable ideologies’ (stories turned frigid) – the Norwegian had their tragedy, the world as a whole had 9/11. To write the story to let others come alive, while also realizing that ‘the other’ is always bigger than ‘our story’ – that’s what we need… “In the beginning was the Word…” (John 1:1). The Word between one man and the other, the Poet creating proximity and distance at the same time, creating tenderness… Like a painter, who caresses the image of his beloved model with a paintbrush, leaving the model herself ‘untouched’…

Well, what kind of storytelling you prefer, doesn’t really matter. However, I’m strongly convinced that what we need today is the art of storytelling. Too many tragedies seem to happen nowadays because of people who live from ‘indisputable ideologies’ (stories turned frigid) – the Norwegian had their tragedy, the world as a whole had 9/11. To write the story to let others come alive, while also realizing that ‘the other’ is always bigger than ‘our story’ – that’s what we need… “In the beginning was the Word…” (John 1:1). The Word between one man and the other, the Poet creating proximity and distance at the same time, creating tenderness… Like a painter, who caresses the image of his beloved model with a paintbrush, leaving the model herself ‘untouched’…