NATIONALISM AND RELIGION (WITH WILLIAM T. CAVANAUGH AND RENÉ GIRARD)

Like any ideology, nationalism sometimes takes totalitarian forms, which blurs the lines between the political left and right. The Soviet Russian motherland was as dear to Stalinist Communists as the German fatherland was to convinced Nazis. Moreover, Stalin and Hitler enjoyed an almost divine status. Totalitarian nationalism thus also raises the question of the distinction between the secular and the religious.

Erik Buys

“KILLING FOR THE NATION, NOT FOR GOD”

Several years ago, theologian William T. Cavanaugh published a startling study of the relationship between the modern nation-state, religion, and violence with his book The Myth of Religious Violence. Professor Cavanaugh further elaborated his research on the subject in subsequent lectures and articles. Since various contemporary superpowers often use religious language, it is worth listening to him carefully.

Defining religion is not that simple. Some definitions of religion take a substantivist approach, based on what people believe. According to that type of reasoning, religious beliefs and practices have to do with God or gods, as opposed to secular ones. “Belief in God or gods is the usual starting place,” notes Cavanaugh, “but as a single criterion it is regarded as too restrictive, because it would exclude some belief systems that generally make lists of world religions, such as Buddhism, Confucianism, and Daoism.”[i] Nor does the more general term transcendence offer a solution, according to the professor. “The meaning of terms like transcendence is almost inevitably modeled on Judeo-Christian theological definitions of transcendence based on the relationship of a Creator God to the created world. […] Transcendence can be used in the Buddhist context only by trying to ignore the Judeo-Christian theological background of the term and making it more vague and more general. […] Once the transcendent becomes the focus of one’s definition of religion, there is no reason to suppose that the generally recognized world religions would exhaust the category. As Timothy Fitzgerald points out, transcendent notions can include ‘the Nation, the land, the principles of humanism, the ancestors, Communism, ātman-brahman, the goddess of democracy and human rights, Cold Speech, Enlightenment (in various quite different senses), the right to private property, witchcraft, destiny, the Immaculate Conception,’ and so on.”[ii]

Religio

The distinction between the religious and the secular becomes arbitrary when the definition of religion is based on substantive criteria. Instead, it is also possible to approach cultural beliefs and practices according to their function, which more strongly integrates the arbitrary nature of the boundary between the religious and the secular. Functionalist approaches stress that how something works in a society is more important than exactly what that something is. “Functionalist approaches are a return to the broadest meaning of the word religio in classical Rome: any binding obligation or devotion that structures one’s social relations,” Cavanaugh points out.[iii] “It does not matter that the U.S. flag does not explicitly refer to a god. It is nevertheless a sacred – perhaps the most sacred – object in U.S. society and is thus an object of religious veneration.[iv] […] It is clear that, among those who identify themselves as Christians in the United States, there are very few who would be willing to kill in the name of the Christian God, whereas the willingness, under certain circumstances, to kill and die for the nation in war is generally taken for granted.”[v]

Modern State Structure

The modern state originates in Europe between 1450 and 1650. Some monarchs no longer tolerate that their subjects recognize forms of government based on ecclesiastical loyalties, or on tribal and feudal ties. “The state ‘creates’ society by replacing the complex overlapping loyalties of medieval societates with one society, bounded by borders and ruled by one sovereign to whom allegiance is owed in a way that trumps all other allegiances,” Cavanaugh summarizes.[vi] “A society is brought into being by the centralization of royal power.”[vii] As a consequence, more traditional social ties begin to erode, while individuals are more self-contained. This ultimately results in an expanded legalistic and bureaucratic state apparatus that manages the relationships between those individuals through contractual arrangements. “The [modern] body politic does not pursue the common good,” Cavanaugh emphasizes, “but instead seeks to liberate the individual to pursue his or her own ends.”[viii] And he continues that “the state in liberalism does not pursue the good, but rather secures peace among varying conceptions of the good.”[ix]

Nationalism

Nevertheless, as social beings, people also need a sense of community that does not depend solely on bureaucratic mediation. The nation-state as a more recent development of political organization comes to fruition in the nineteenth century and expresses nationalistic sentiments. Nationalism first emerges in the eighteenth century. “It is only after the state and its claims to territorial sovereignty are established that nationalism arises to unify culturally what had been gathered inside state borders,” Cavanaugh notes.[x] “Until the nineteenth century, states lacked the internal cohesion necessary to be nations.”[xi] Italy, for example, had only 10 percent Italian-speaking citizens at its inception in 1860, to which famed Italian patriot Massimo d’Azeglio said, “We have made Italy. Now we have to make Italians.”[xii] According to Cavanaugh, three factors played a decisive role in the promotion of nationalist sentiments by nineteenth-century elites: “The first was the increasing influence of the state over education, by means of which a common history and common myths of origin were told. The second was the spread of standardized language by means of print media. […] Finally, war had a profound influence on the rise of nationalism. The United States became a nation-state only after the crisis of the Civil War, and nationalism took a quantum leap in the massive mobilization of society for World War I. The questions of language and war are often intertwined: a language is just a dialect with an army, as the saying goes.”[xiii]

War

Inwardly, war creates more unity among the citizens of a nation-state, outwardly more hostility toward other nations. Initially, war always strengthens the domestic position of a Putin or a Netanyahu. The paradox is that the state promises to protect its citizens from violence that can really only arise on the basis of the hostility associated with the formation of that very same state. Moreover, political elites demand resources from citizens to make that protection a reality.[xiv] Cavanaugh reveals the ambiguous nature of that exercise of power: “The claim that emerging states offered their citizens protection against violence ignores the fact that the state itself created the threat and then charged its citizens for reducing it. What separated state violence from other kinds of violence was the concept of legitimacy, but legitimacy was based on the ability of state-makers to approximate a monopoly on violence within a given geographical territory. In order to pursue that monopoly, elites found it was necessary to secure access to capital from the local population, which was accomplished in turn either by the direct threat of violence or the guarantee of protection from other kinds of violence.”[xv]

Monopoly on Violence

From modern times onward, the state – evolving from absolute monarchies to constitutional democracies – acquires an authority that holds a monopoly on the use of force, but actually every society structures itself on the basis of an authority that distinguishes permissible from impermissible violence. And that authority remains in the saddle as long as everyone remains blind to its accidental creation. Taboos and rituals are legitimized by collective myths that are put beyond any doubt. Violence and what a society associates with it is taboo, unless it is given space in a ritualized – and thus controlled – manner. In the Bolivian Andes, for example, indigenous peoples want to avoid violence as a result of famine. Nevertheless, to beg a good harvest from the mountain spirits, villagers beat each other to the point of blood during the Tinku ritual. Those fights can even end in death. That sacrificial violence is touted in the community’s myths. It is supposed to be a vaccine of controlled violence against a possible epidemic of devastating violence after crop failures.

Heroes

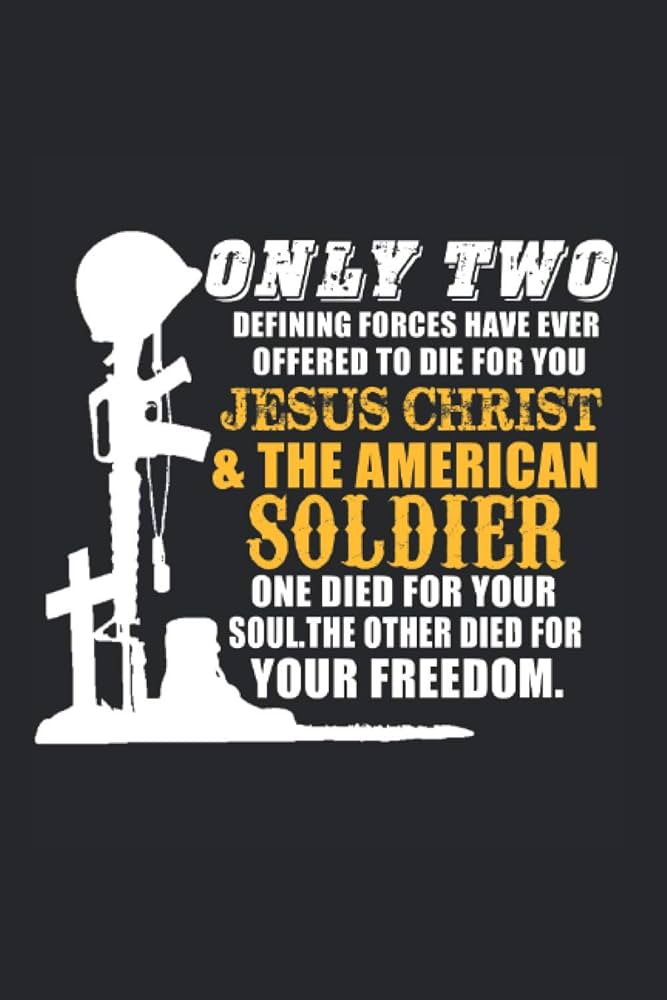

The nation-state presents itself as a bulwark against potential violence from foreign powers. And although its subjects are not supposed to meet their end in a violent manner, in wartime the state still expects its soldiers to give their lives as heroes for the nation. That kind of sacrificial violence is considered a permissible dam against the supposedly unlawful, destructive violence of the enemy. “Blood sacrifice is an act of both creation and salvation,” Cavanaugh argues. “At the ceremonies marking the fiftieth anniversary of D-Day in 1994, for example, President Bill Clinton remarked of the soldiers that died there both that ‘they gave us our world’ and that ‘they saved the world.'”[xvi] In his lectures, the American often points to a saying that can be read in his homeland on stickers and T-shirts: “Only two defining forces have ever offered to die for you: Jesus Christ and the American soldier.” The radical difference, of course, is that the former dies because he refuses to kill and thus actually stops violence, while the latter dies when he has been ordered to eliminate an enemy. Moreover, recent history, with wars on an industrial scale, proves that a willingness to die on the part of all combatants is ultimately anything but a dam against destructive violence. “All who take the sword will perish by the sword,” Jesus rightly asserts in the Gospel of Matthew (26:52).

IMITATION OF CHURCH RIVALS

The nation-state not only legitimizes itself as protection against potential violence from foreign enemies, but also as protection against potential violence from domestic threats. “If the nation-state tends to elide actually existing internal differences, it tends simultaneously to accentuate external differences,” William Cavanaugh concludes[xvii], despite the promises of a tolerant and pluralistic world by liberalism.

Internally, a sovereign state does not tolerate other political authorities and therefore undermines the loyalty of individuals to tribal, feudal or ecclesiastical authorities. Warfare plays a crucial role in this regard. “War requires a direct disciplinary relationship between the individual and the state, and so has served as a powerful solvent of the loyalties of individuals to social groups other than the state,” Cavanaugh analyzes.[xviii] “In the absence of a common good or telos, the state can only expand its reach, precisely in order to keep the welter of individuals pursuing their own goods from interfering with each other. Where there is a unitary simple space, pluralism of ends will always be a threat. To solve this threat, the demand will always be to absorb the many into the one. In the absence of shared ends, devotion to the state itself as the end in itself becomes ever more urgent. The result is not true pluralism but an ever-increasing directness of relationship between the individual and the state as foundation of social interaction.”[xix] The devotion to the state requires all citizens to be committed to the so-called common good. “What is ‘common’ is reduced to what fits into national borders, and what is good can be purchased at the expense of what is good for other nation-states,” Cavanaugh continues.[xx] “But the wealthier classes are far more effective at presenting their interests as being national interests,” he warns.[xxi] Behind the so-called common good often lie the financial and economic interests of privileged groups.

Elizabeth I

Initially, the emerging states primarily see the Church as a rival to their authority, also because the community of the faithful is not restricted by territorial boundaries. Not coincidentally, the first modern monarchs imitated Church customs to take the place of their rival. For example, “at the same time that Elizabeth I was suppressing celebrations of the feast of Corpus Christi, she was appropriating significant symbolic aspects of the feast with herself substituted for the host. Elizabeth made a frequent practice of being processed around under a canopy modeled after those used for Corpus Christi feasts. A royal cult complete with shrines and pilgrimages grew up around the person of Elizabeth,” Cavanaugh explains.[xxii]

Civil Religion

In addition, enlightened philosophers draw inspiration from the unifying nature of the Church to advocate a similar sense of unity in the state. They use the age-old term religio to denote what should unite citizens. Religion in that sense thus also implies the political realm. “The term civil religion was introduced by Rousseau in the eighteenth century,” Cavanaugh clarifies. “In the last chapter of The Social Contract, Rousseau proposes an explicit civil religion as a cure for the divisive influence of Christianity, which had divided people’s loyalties between church and state. Rousseau does not wish to erase Christianity entirely, but to reduce it to a ‘religion of man’ that ‘has to do with the purely inward worship of Almighty God and the eternal obligations of morality, and nothing more.’ Civil religion, on the other hand, is the fully public cult of the nation-state.”[xxiii]

Myth-Making

The modern state exercises increasing control over religions that deviate from its civil religion, based on the idea that those deviant religions, if not curbed, lead to destructive violence. Wars of religion from the Reformation onward allegedly prove that. Cavanaugh opposes that view and shows that theological disputes often did not play a decisive role in the wars of the period. Catholics, for example, entered into alliances with Protestants against other Catholics just as much as Protestants entered into alliances with Catholics against other Protestants. So, there is myth-making concerning those religions, on the basis of which the state justifies their marginalization and increases its own power. Gradually, that state no longer calls its own binding obligations religious, so that a so-called secular state order is clearly distinguished from religious organizations.

Divide

“The religious-secular distinction is part of the legitimating conceptual apparatus of the modern Western nation-state. […] This distinction was born with a new configuration of power and authority in the West and was subsequently exported to parts of the world colonized by Europeans,” Cavanaugh notes. “To mix religion with public life was said to court fanaticism, sectarianism, and violence. The religious-secular divide thus facilitated the transfer in the modern era of the public loyalty of the citizen from Christendom to the emergent nation-state. Outside the West, the creation of religion and its secular twin accompanied the attempts of colonial powers and indigenous modernizing elites to marginalize certain aspects of non-Western cultures and create public space for the smooth functioning of state and market interests.”[xxiv]

René Girard

Today also, there is a perception that anything labeled religious is irrational and encourages violence. “When public discourse blames terrorist attacks on religious fanaticism, common sense can see that there are dangerous pathologies linked to some of what is called religion,” Cavanaugh acknowledges. “The problem with the myth of religious violence is not that it condemns certain kinds of violence, but that it diverts moral scrutiny from other kinds of violence. Violence labeled religious is always reprehensible; violence labeled secular is often necessary and sometimes praiseworthy.”[xxv] Cavanaugh refers to the work of French-American thinker René Girard (1923-2015) to clarify further:

“Girard argues that the belief in a divide between the religious and the secular itself has a religious purpose: ‘The failure of modern man to grasp the nature of religion has served to perpetuate its effects. Our lack of belief serves the same function in our society that religion serves in societies more directly exposed to essential violence.’ What he means is that the belief in a fundamental divide between the rational, secular state and an irrational, mystifying religion itself has a mystifying function, a function that staves off the disintegration of the social order. It is for this reason that Girard states, ‘There is no society without religion because without religion society cannot exist.’ Even secular societies are religious. Girard does, however, hold out the hope that society can be progressively demythologized by an increased consciousness of the mechanism of victimization. This is accomplished, however, not by a progressive secularization, but by the counter-mythical thrust of the Christian story found in the scriptures. For Girard, any moves that Western culture has made away from scapegoating are not the result of the Enlightenment and secularization, but the result of the gospel’s influence.”[xxvi]

Questioning Idolatry

From Girard’s and Cavanaugh’s perspective, the question is not so much whether nationalism is religious, but rather why an enemy’s violence is sometimes called religious while one’s own violence is supposedly secular, and what kind of legitimating discourses lie behind those statements. The Christian tradition, among others, speaks of a transcendence that exposes and questions any human idolatry of violence. “Understanding and defusing violence in our world requires clear moral vision, of not only the faults of others but our own,” Cavanaugh concludes. “Violence feeds on the need for enemies, the need to separate us from them. Such binary ways of dividing the world make the world understandable for us, but they also make the world unlivable for many. Doing away with the myth of religious violence is one way of resisting such binaries and, perhaps, turning some enemies into friends.”[xxvii]

[A Dutch version of this article appeared in Tertio Magazine; click here to read it.]

[i] Cavanaugh, William T. (2009). The Myth of Religious Violence. New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press, 102.

[ii] Ibid., 103.

[iii] Ibid., 106.

[iv] Ibid., 106.

[v] Ibid., 122.

[vi] Cavanaugh, William T. (2011). Migrations of the Holy: God, State, and the Political Meaning of the Church. Michigan/Cambridge: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 19.

[vii] Ibid., 14.

[viii] Ibid., 23.

[ix] Ibid., 25.

[x] Ibid., 11.

[xi] Ibid., 34.

[xii] Ibid., 34.

[xiii] Ibid., 34.

[xiv] Ibid., 15.

[xv] Ibid., 16.

[xvi] Cavanaugh, William T. (2009). The Myth of Religious Violence. New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press, 118.

[xvii] Cavanaugh, William T. (2011). Migrations of the Holy: God, State, and the Political Meaning of the Church. Michigan/Cambridge: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 38.

[xviii] Ibid., 27.

[xix] Ibid., 31-32.

[xx] Ibid., 38-39.

[xxi] Ibid., 38.

[xxii] Cavanaugh, William T. (2009). The Myth of Religious Violence. New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press, 175.

[xxiii] Ibid., 114.

[xxiv] Ibid., 120-121.

[xxv] Ibid., 121.

[xxvi] Ibid., 40-41.

[xxvii] Ibid., 230.