SINGER-SONGWRITERS ON LOVE AND DEATH

Erik Buys

From Aretha Franklin to Madonna, Bob Marley to U2, and blues to hip-hop, many famous pop artists draw on the Bible to express human experiences. The work of Nick Cave, Leonard Cohen and Bruce Springsteen converges in a special way when it comes to love and death. This article brings these singer-songwriters together in a triptych for the colder seasons.

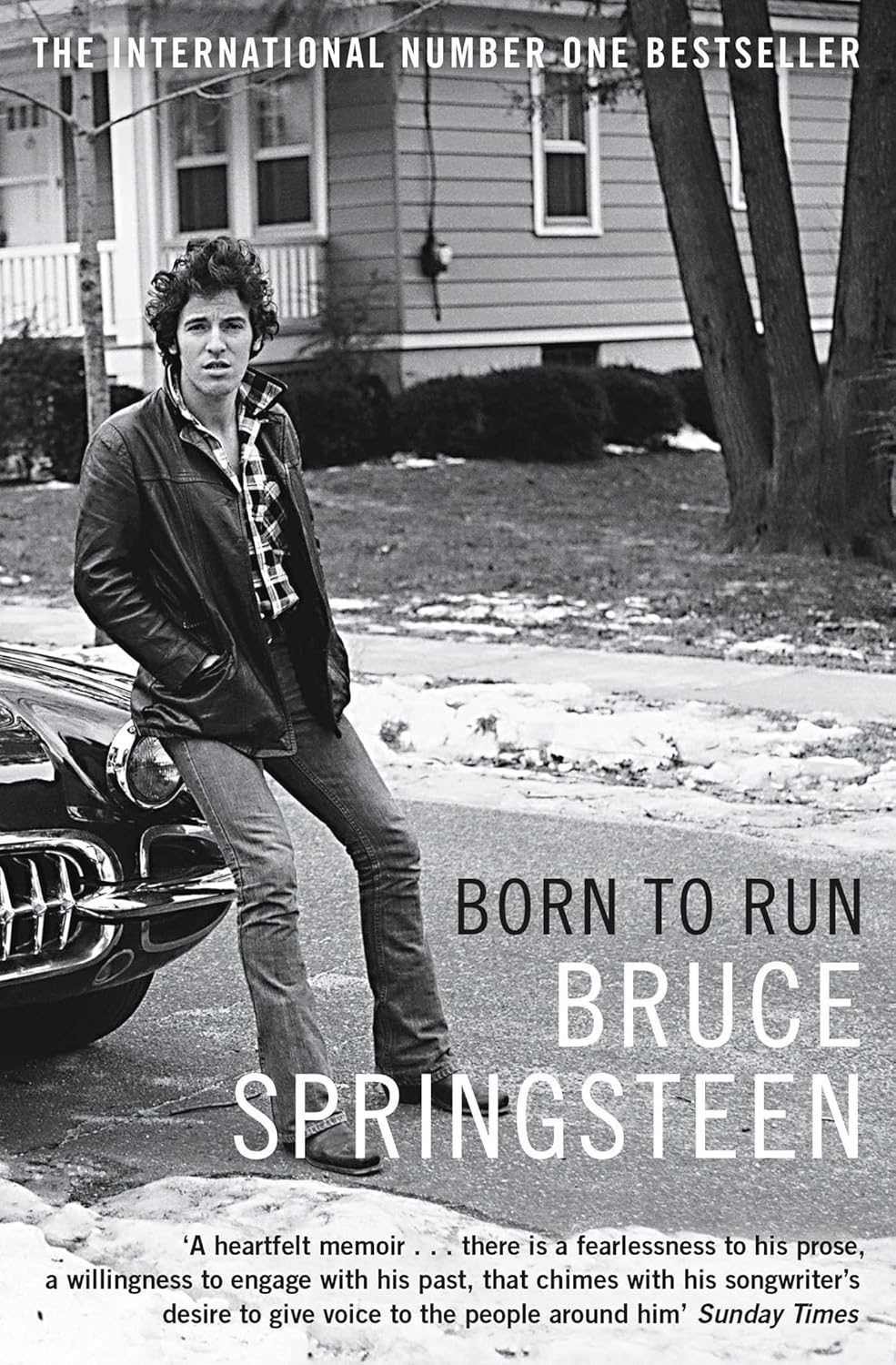

“ADAM RAISED A CAIN”

As a child, he was sometimes terrified of his father, but he nevertheless refused to let dad silence him. Bruce Springsteen has sung impressively about the bond with his father Douglas (1924-1998) throughout his musical career. The love between father and son found its way through wounds and frustrations. Due to his Catholic background, Springsteen expresses that history with Biblical images, making it recognizable to anyone who struggles with the human tendency to consider someone else dead.

The awareness of something like mortal sin runs like a common thread through Springsteen’s representation of the relationship between parents and their children. Violent evil is contagious and is passed on from generation to generation. Revenge calls for revenge. The Bible tells in various tones how people do violence to each other under the influence of an addiction to power, wealth, honor or pride, and pleasure. Add to that the lazy indifference of those who bathe in royal luxury, and the anger that results from wounded pride, and you arrive at what the Christian tradition calls the seven deadly sins. After all, wounded pride usually results in envy, the center of the seven deadly sins, which, according to the Italian poet Dante Alighieri (1265-1321), is another name for the devil.

Envy

Springsteen sees the diabolical power of envy at work between him and his father. In Born to Run, his autobiography of the same title as the album that meant his big breakthrough in 1975, he observes (Bruce Springsteen. Born to Run. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2016; p. 29): “My dad’s desire to engage with me almost always came after the nightly religious ritual of the ‘sacred six-pack.’ One beer after another in the pitch dark of our kitchen. It was always then that he wanted to see me and it was always the same. A few moments of feigned parental concern for my well-being followed by the real deal: the hostility and raw anger toward his son, the only other man in the house. It was a shame. He loved me but he couldn’t stand me. He felt we competed for my mother’s affections. We did.”

Humiliation

Both Bruce Springsteen and his father felt rejected. That kind of experience, so deeply touched upon in the Biblical traditions, often hindered their mutual love. It is no coincidence that Springsteen already in 1978 released a song with the title Adam Raised a Cain on his fourth album, Darkness on the Edge of Town. In the last verse of that song he writes:

“In the Bible Cain slew Abel

And East of Eden he was cast

You’re born into this life paying

For the sins of somebody else’s past

Daddy worked his whole life for nothing but the pain

Now he walks these empty rooms looking for something to blame

You inherit the sins, you inherit the flames”

In his autobiography, Springsteen describes how his father grew up in the shadow of his older sister Virginia (1921-1927), who died in a car accident at the age of five. The trauma of that loss marked Bruce’s grandmother and the relationship with her son Douglas, and later also with her grandson. The fear of having to say goodbye to another child made her overprotective, which on the one hand resulted in extreme pampering and on the other hand in a sometimes suffocating need for control, which in turn caused trauma.

Springsteen recalls an event from his father’s past that exemplifies the way his old man felt humiliated by his own mother (p. 29): “One evening at the kitchen table, late in life, when he was not well, [my father] told me a story of being pulled out of a fight he was having in the school yard. My grandmother had walked over from our house and dragged him home. He recounted his humiliation and said, eyes welling… ‘I was winning… I was winning.’ He still didn’t understand he could not be risked. He was the one remaining, living child. My grandmother, confused, could not realize her untempered love was destroying the men she was raising. I told him I understood, that we had been raised by the same woman in some of the most formative years of our lives and suffered many of the same humiliations. However, back in the days when our relationship was at its most tempestuous, these things remained mysteries and created a legacy of pain and misunderstanding.”

Reflection

Springsteen’s father wanted to do away with himself as the soft mama’s boy, because he saw in it a rejection of the man he thought he should be. Springsteen gradually sees that pursuit as the source of his father’s fits of rage, and he learns to understand them (p. 29): “Inside…, beyond his rage, he harbored a gentleness, timidity, shyness and a dreamy insecurity. These were all the things I wore on the outside and the reflection of these qualities in his boy repelled him. It made him angry. It was ‘soft.’ And he hated ‘soft.’ Of course, he’d been brought up ‘soft.’ A mama’s boy, just like me.”

MEDIA VITA IN MORTE

In the Bible, the word ‘death’ refers not only to a possible physical condition, but often also to a lack of love, as Springsteen regularly experienced this in the relationship with his father. Media vita in morte sumus, “in the midst of life we are in death,” is the Gregorian antiphon for sins. According to the same Biblical perspective, the extent to which people respect each other and give each other breathing space creates opportunities for a fulfilling human life. “This son of mine was dead and is alive again” (Luke 15:24a), a father exults in a well-known parable of Jesus, at the moment when his youngest son reconnects with the home front years after a rude farewell.

The Genesis story of Cain and Abel (Genesis 4:1-16) resonates in that parable of the prodigal son. Cain feels rejected by the Lord because the Lord does not pay attention to his offering, although the Lord does care about Cain when the latter is overcome by anger. But that is to no avail. Cain is so jealous of his younger brother Abel, whose offering was appreciated by the Lord, that he eventually murders Abel. Cain had apparently not offered his gift to the Lord so much out of love, but out of pride. If you love someone, you are delighted with the other person’s joy, even if, for example, he or she is mainly happy because of the birthday present of a mutual friend, and not about your own present. The same holds true for the eldest son in Jesus’ parable, when he discovers that his father is preparing a feast for his returned younger brother. If he had stayed with his father all those years out of love, and not, for example, to outdo his younger brother, he would have rejoiced at his father’s joy. Instead, he feels rejected, and in anger he disregards the kinship with his brother. Consumed by the jealousy of a wounded pride, he, like Cain, lacks the gratitude for the love that indeed is his part. Nevertheless, his father continues to offer him that love: “Son, you are always with me, and all that is mine is yours” (Luke 15:31).

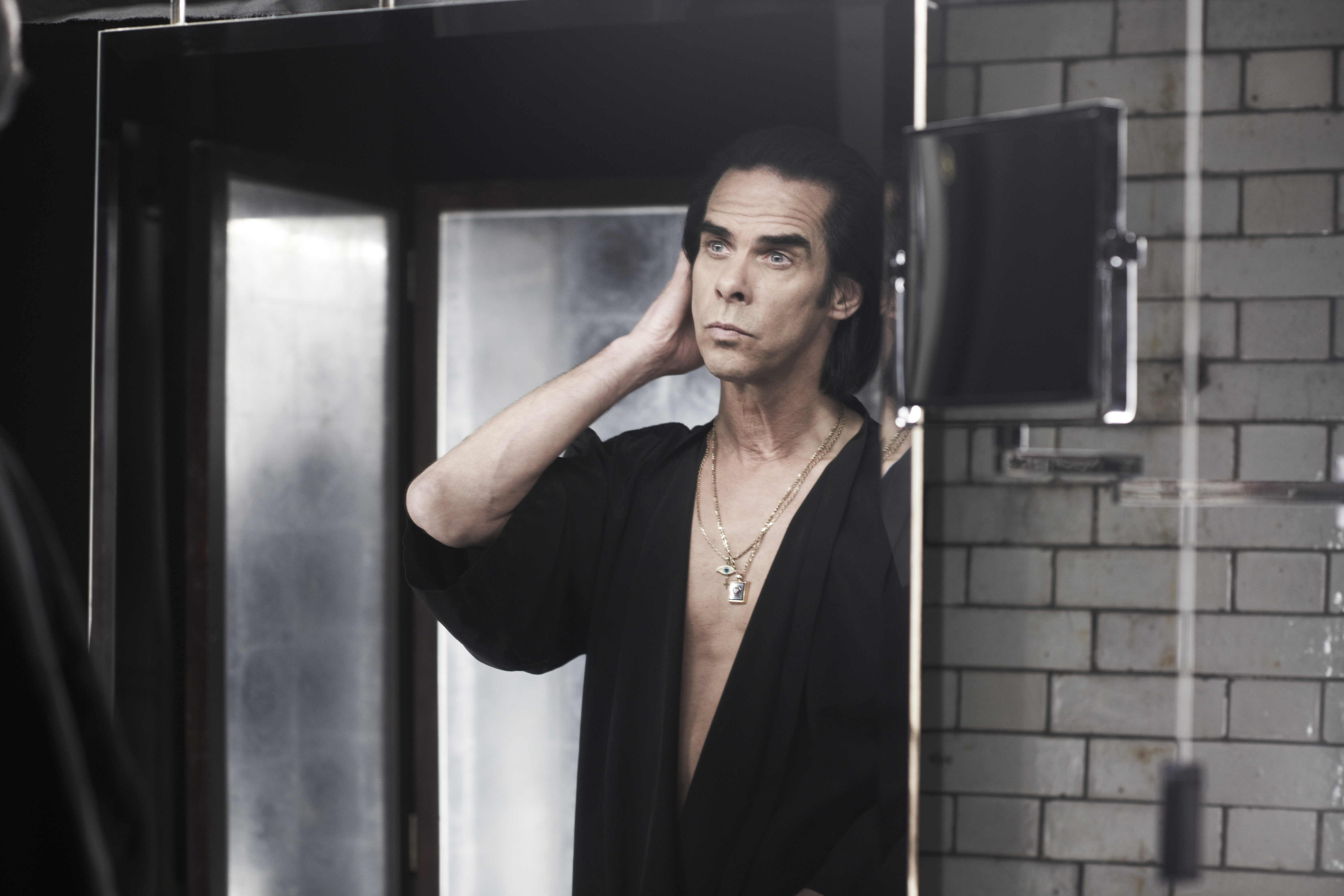

“PERHAPS GOD IS THE TRAUMA ITSELF”

Like Bruce Springsteen, Nick Cave sings about the relationship between father and son, but his injury is of a different nature than Springsteen’s: in 2015 his fifteen-year-old son Arthur (2000-2015) died after falling off a cliff. The 2019 album Ghosteen and the interview book Faith, Hope and Carnage, published three years later, are part of his grieving process, which was further burdened in May 2022 by the death of his eldest son Jethro (1991-2022).

Cave has dealt with the loss of his children differently than Springsteen’s grandmother. Instead of desperately clinging to a false sense of security, he surrenders to the dynamic of a vulnerable love. This is just as infectious and, in Cave’s case, just as Biblically inspired as the dynamic of violence, but it does not cause new devastating wounds. When asked whether he believes in redemption in the Christian sense of the word, Cave answers in the interview book (Nick Cave and Seán O’Hagan. Faith, Hope and Carnage. Edinburgh: Canongate Books, 2022; p. 28):

“I feel that when I have done something to hurt an individual, say, that the wrongdoing also affects the world at large, or even the cosmic order. I believe that what I have done is an offence to God and should be put right in some way. I also believe our positive individual actions, our small acts of kindness, reverberate through the world in ways we will never know. I guess what I am saying is – we mean something. Our actions mean something. We are of value.”

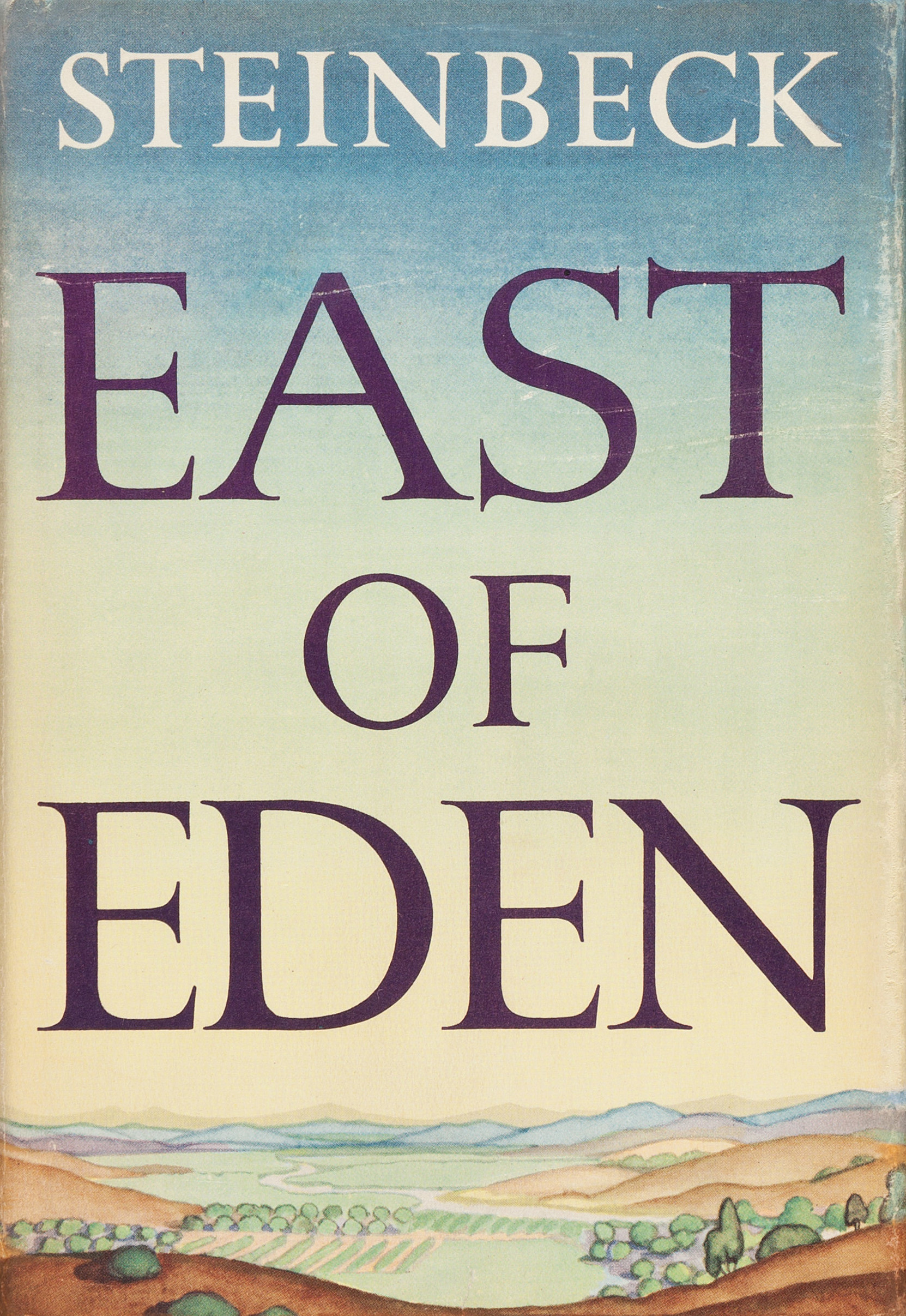

Talking about the impact of the Christian story regarding his outlook on life, Cave further claims (p. 20): “I’m drawn to what many people would see as traditional Christian ideas. I’m particularly fascinated with the Bible and in particular the life of Christ. It has been a powerful influence on my work one way or another from the start.” Springsteen has also never made a secret of the fact that Bible stories give him insight into his own experiences. Nor does he gloss over the influence of the Catholic imagination of novelists such as Nobel Prize winner John Steinbeck (1902-1968), and National Book Award winners Flannery O’Connor (1925-1964) and Walker Percy (1916-1990), or of filmmakers such as John Ford (1894-1973) and Terrence Malick. The influence of John Steinbeck’s East of Eden shines through in Springsteen’s characterization of his father in Adam Raised a Cain. The novel uses the story of Cain and Abel as a leitmotif to tell the adventures of two American families, from the early 20th century to the end of World War I. The Chinese butler Lee, one of the characters, at one point explains the story of Cain as “a chart of the rejected soul” (see full quote below).

FROM EAST OF EDEN (JOHN STEINBECK):

“I think this [story of Cain and Abel] is the best-known story in the world because it is everybody’s story. I think it is the symbol story of the human soul. I’m feeling my way now – don’t jump on me if I’m not clear. The greatest terror a child can have is that he is not loved, and rejection is the hell he fears. I think everyone in the world to a large or small extent has felt rejection. And with rejection comes anger, and with anger some kind of crime in revenge for the rejection, and with the crime guilt – and there is the story of mankind. I think that if rejection could be amputated, the human would not be what he is. Maybe there would be fewer crazy people. I am sure in myself there would not be many jails. It is all there – the start, the beginning. One child, refused the love he craves, kicks the cat and hides the secret guilt; and another steals so that money will make him loved; and a third conquers the world – and always the guilt and revenge and more guilt. The human is the only guilty animal. Now wait! Therefore I think this old and terrible story is important because it is a chart of the soul – the secret, rejected, guilty soul.”

Desperate Longing

In a 1998 interview for Double Take Magazine by Will Percy, Walker Percy’s cousin, Springsteen looks tenderly at those who feel rejected or ostracized. He recognizes the often desperate longing for love in those people, the longing to find a place to call home, that was also hidden behind his father’s angry outbursts (June Skinner Sawyers. Racing in the Street: The Bruce Springsteen Reader. New York: Penguin Books, 2004; p. 309): “I think that’s been a theme that’s run through much of my writing: the politics of exclusion. My characters aren’t really antiheroes. Maybe that makes them old-fashioned in some way. They’re interested in being included, and they’re trying to figure out what’s in their way.” The darkness of trauma and frustration that sometimes hung over the relationship with his father is not an inevitable fate for Springsteen. In his autobiography, he downplays the caricature he made elsewhere of their relationship, precisely because he has gained insight into the origins of his father’s problems (p. 26): “I haven’t been completely fair to my father in my songs, treating him as an archetype of the neglecting, domineering parent. It was an East of Eden recasting of our relationship, a way of ‘universalizing’ my childhood experience. Our story is much more complicated.”

Vulnerable Love

Nick Cave also discovers love and the longing for it as the undercurrent without which no trauma can exist. Insofar as Cave sees the divine as the dynamic of a vulnerable, nonviolent love, he even considers in the interview book (p. 31): “Perhaps God is the trauma itself.” Vulnerable love does not allow itself to be determined by the sorrow and suffering that is a possible consequence of its self-giving. Love gives itself, despite possible pain. Love is the openness to trauma. It does not allow itself to be overpowered by grief, but it becomes all the more palpable in the experience of the absence of loved ones, with whom it does not give up the bond. Cave finds solace in that painfully palpable, yet indestructible, quality of love (pp. 31-32): “As far as I can see, there is a transformative aspect to this place of suffering. We are essentially altered or remade by it. Now, this process is terrifying, but in time you return to the world with some kind of knowledge that has something to do with our vulnerability as participants in this human drama. […] My love of the world and for people feels stronger, I mean that quite qenuinely, and I don’t think I’m alone in feeling that. I think this is what happens when we experience collective traumas such as this. We become connected by our mutual vulnerability.” Cave also describes what happens to ourselves when we spend time in the place of vulnerability (p. 41): “The more time you spend there, the less worried you become of how you will be perceived or judged, and that is ultimately where the freedom is.” According to Cave, there is a beauty in grief, for it has an ever-connecting love as its true source (pp. 41-42): “If you have been fortunate enough to have been truly loved, in this world, you will also cause extraordinary pain to others when you leave it. That’s the covenant of life and death, and the terrible beauty of grief.”

Darker

Three weeks before his death, Leonard Cohen (1934-2016) released You Want It Darker. The album’s title song is a mystical reflection on the bond between love and death, reminiscent of what Bruce Springsteen and Nick Cave say about it. The song You Want It Darker not only evokes Biblical imagery, but also literally quotes from the Jewish Kaddish, the prayer for the dead:

“Magnified and sanctified

Be Thy Holy Name”

In addition, the song refers to a pericope in Genesis in which the phrase “Hineni” – “Here I am” – occurs at three key moments, namely the story of Abraham who feels called to sacrifice his eldest son Isaac. The famous English rabbi and philosopher Jonathan Sacks (1948-2020) pointed this out in an extensive commentary on You Want It Darker. When Abraham is about to sacrifice Isaac, something strange happens. God lets Abraham know that He does not want a human sacrifice at all. He asks Abraham to let the boy live and to sacrifice a ram in his place. This is significant, because the ram is a symbol of male leadership and violence. The story thus shows a God who encourages people to sacrifice their lust for power and their possibly violent rivalry, so that they do not kill each other. Once again, the divine is recognized in the dynamic of a nonviolent love. Abraham becomes a father who gives his son the space to live. Not coincidentally, this text contains the first mention of the word ‘love’ in the Hebrew Bible. In his song, Cohen criticizes “the human frame” that “vilifies, crucifies” God’s Holy Name whenever people assume that they must kill in God’s name. But, Cohen suggests, truly divine love takes no part in the violence, and retreats into an ever darker darkness – hence: “You want it darker.” This is not to abandon the world to its fate, but to give people the chance to shine the light of peaceful love, even though all too often “we kill the flame.”

“WE ARE GHOSTS OR WE ARE ANCESTORS IN OUR CHILDREN’S LIVES”

Like Nick Cave’s traumatic experiences, the wounds in the relationship between Bruce Springsteen and his father gradually make themselves felt as the unfulfilled desire of love. This is evident on July 17 and 18, 2018, when Springsteen on Broadway is recorded live for Netflix. On December 14 of that year, the audio album of that recording is also released.

During his performance, Springsteen not only highlights the conflicts with his father, but also their reconciliation process. In the song My Father’s House he tells about a dream that expresses the longing for his father. The fourth verse speaks volumes:

“I awoke and I imagined the hard things that pulled us apart

Will never again, sir, tear us from each other’s hearts

I got dressed, and to that house I did ride from out on the road,

I could see its windows shining in light”

In his commentary on the song, Springsteen talks about the love-hate relationship with his father, but also how he imitated him to feel his closeness, and how he explains to his father in a dream that he is proud of the man Springsteen himself has become because of it – a man like he imagines his father to be. Later in the set, Springsteen performs Long Time Comin’, in which he wants to make a new beginning, in which he wants to be born again:

“I’m riding hard carryin’ a catch of roses

And a fresh map that I made

Tonight I’m gonna get birth naked and bury my old soul

And dance on its grave”

The death of an evil past, with the experience of rejection that his soul suffered, is linked for Springsteen to the birth of his children and the love they arouse in him:

“Now down below and pullin’ on my shirt

I got some kids of my own

Well if I had one wish in this godforsaken world, kids

It’d be that your mistakes would be your own

Yeah your sins would be your own”

Springsteen does not want to burden his children with the legacy of the violence he himself experienced. There has been an undeniable process of forgiveness between him and his father. As a result, they are no longer defined by the traumas and frustrations they have suffered, and Springsteen can give his children breathing space, including the space to make their own mistakes. In his autobiography, Springsteen points out the miraculous effect that the vulnerability of a newborn can have on tumultuous relationships. A fragile child has the paradoxical power to unleash a caring love that pushes conflicts into the background. Springsteen sees this happen at the birth of his youngest sister Pam (p. 30): “The whole house was caught up in the excitement of Pam’s birth and our family came together. With my mom in the hospital, my dad stepped up and took care of us, burning breakfast, helping us get dressed for school (sending me there in my mother’s blouse, to Virginia’s roaring laughter). The house lit up. Children bring with them grace, patience, transcendence, second chances, rebirth and a reawakening of the love that’s in your heart and present in your home. They are God giving you another shot. My teenage years with my father were still not great but there was always the light of my little sister Pam, living proof of the love in our family. I was enchanted with her. I was thankful for her. I changed her diapers, rocked her to sleep, ran to her side if she cried, held her in my arms and forged a bond that exists to this day.”

Redemption

When Springsteen himself becomes a father for the first time, at the end of his wife Patti’s pregnancy, he experiences his old father again, as he did in the days after the birth of his youngest sister Pam, but more intensely. In his commentary on Long Time Comin’ during the Broadway set, he talks about it: “My dad, never a talkative man, blurted out, ‘You’ve been very good to us.’ And I nodded, and he says, ‘And I wasn’t very good to you.’ And the room just stood still. As to my shock, the acknowledgeable was being acknowledged, and if I didn’t know better I would’ve sworn an apology of some sort was being made, and it was. Here in the last days before I was to become a father, my own father was visiting me to warn me of the mistakes that he had made, and to warn me not to make them with my own children. To release them from the chain of our sins, my father’s and mine and our fathers before, that they may be free, to make their own choices and to live their own lives.”

“We are ghosts or we are ancestors in our children’s lives. We either lay our mistakes, our burdens upon them, and we haunt them, or we assist them in laying those old burdens down, and we free them from the chain of our own flawed behavior. And as ancestors, we walk alongside of them, and we assist them in finding their own way, and some transcendence. My father, on that day, was petitioning me, for an ancestral role in my life after being a ghost for a long time. He wanted me to write a new end to our relationship, and he wanted me to be ready for the new beginning that I was about to experience. It was the greatest moment in my life with my dad, and it was all that I needed.”

Dearly Departed

Before singing Born to Run as the finale of his Broadway concert, Springsteen reflects on how his deceased loved ones remain present in who he has become. He gratefully testifies to his unbreakable bond of love with the dearly departed, which did not die even with death, and which, through him, leaves traces for others. Springsteen describes visiting his old neighborhood just before he began writing his autobiography, and ends his concert with an age-old prayer. “My dead father’s still with me every day and I miss him,” Springsteen says. “I visit him every night, a little bit, that’s a grace-filled thing. … I get to see him be with Clarence a little bit every night. And Danny, Walter, and Bart, my own family, so many of them gone from these houses that are now filled by strangers but the soul is a stubborn thing. Doesn’t dissipate so quickly. Souls remain. They remain here in the air, in empty space, in dusty roots, in sidewalks that I knew every single inch of like I knew my own body, as a child, and in the songs that we sing, you know. That is why we sing.” Nick Cave sounds like Springsteen when he experiences the presence of his late son Arthur in his songs on Ghosteen (p. 14): “I think Ghosteen, the music and the lyrics, is an invented place where the spirit of Arthur can find some kind of haven or rest. … And I don’t even mean that in a metaphorical way, I mean that quite literally. This isn’t an idea I have articulated before, but I feel him roaming around in the songs.”

Our Father

Springsteen continues to muse in his introduction to Born to Run on Broadway: “I just want to commune with the old spirits, stand in their presence, feel their hands on me. One more time. Anyway, once again I stood in the shadow of my old church, you know what they say about Catholics – yeah, there’s no getting out. They gotcha, the bastards got you when the getting was good. They did their work hard and they did it well, because the words of a very strange but all too familiar benediction came back to me that evening. And I want to tell you these were words that as a kid, I mumbled these things, I sing-songed them, I chanted them, bored out of my mind, in an endless drone before class every day… Every day the green blazer, the green tie, the green trousers, the green socks of all of Saint Rose’s unwilling disciples, you know. But for some damn reason, as I sat there on my street that night, mourning my old tree, and once again surrounded by God, those were the words that came back to me and they flowed differently. ‘Our Father who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name. Thy kingdom come, thy will be done, on this earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day, just give us this day and forgive us our sins, our trespasses, as we may forgive those who trespass against us, lead us not into temptation but deliver us from evil, all of us, forever and ever, Amen.’ And may God bless you, your family, and all those that you love. And thanks for coming out tonight.”

Resurrection

With those words Springsteen responds to the call, expressed in the first letter of John, not to be like Cain, whose actions were motivated by pride, but to pass “from death to life” by the nonviolent and forgiving love embodied in the person of Christ: “For this is the message which you have heard from the beginning, that we should love one another, and not be like Cain who was of the evil one and murdered his brother. And why did he murder him? Because his own deeds were evil. We know that we have passed out of death into life, because we love the brethren. He who does not love remains in death” (1 John 3:11-12a.14).

[A Dutch version of this article first appeared in Tertio Magazine; click here for pdf.]