From the Dominican Republic to Australia, from the United States of America to countries all over Europe, from Brazil to India and South Korea, from the left to the right in political quarters, from the world of science and the humanities, from believers and atheists alike, from media big (e.g. The New York Times) and small (e.g. Provinciale Zeeuwse Courant): René Girard received numerous accolades at his passing. To cite just a few examples, in honor of this “Darwin of the human sciences”:

René Girard was one of the leading thinkers of our era – a provocative sage who bypassed prevailing orthodoxies and “isms” to offer a bold, sweeping vision of human nature, human history and human destiny.

René Girard was one of the leading thinkers of our era – a provocative sage who bypassed prevailing orthodoxies and “isms” to offer a bold, sweeping vision of human nature, human history and human destiny.

The renowned Stanford French professor, one of the 40 immortels of the prestigious Académie Française, died at his Stanford home on Nov. 4 at the age of 91, after long illness.

Fellow immortel and Stanford Professor Michel Serres once dubbed him “the new Darwin of the human sciences.” The author who began as a literary theorist was fascinated by everything. History, anthropology, sociology, philosophy, religion, psychology and theology all figured in his oeuvre.

International leaders read him, the French media quoted him. Girard influenced such writers as Nobel laureate J.M. Coetzee and Czech writer Milan Kundera – yet he never had the fashionable (and often fleeting) cachet enjoyed by his peers among the structuralists, poststructuralists, deconstructionists and other camps. His concerns were not trendy, but they were always timeless.

READ MORE: Stanford Report, November 4, 2015

Many scholars have claimed that René Girard’s mimetic theory is one of the most important insights of the 20th century. This morning brought the news that René has passed away at age 91. “Girardians,” as we are called, have been on social media sharing our sorrow at his passing, but also our profound sense of gratitude for this giant among human beings. We stand on his shoulders. And our vision is all the clearer for it.

READ MORE: Patheos, November 4, 2015

Dans un communiqué, le président de la République, François Hollande, a salué la mémoire du philosophe et académicien français René Girard: «C’est un intellectuel exigeant et passionné, exégète à la curiosité sans limite, théoricien brillant et à l’esprit fondateur, enseignant et chercheur atypique aimant aller à contre-courant, René Girard était un homme libre et un humaniste dont l’œuvre marquera l’histoire de pensée», affirme le chef de l’Etat.

READ MORE: Le Figaro, November 5, 2015

Fondateur de la « théorie mimétique », ce franc-tireur de la scène intellectuelle avait bâti une œuvre originale, qui conjugue réflexion savante et prédication chrétienne. Ses livres, commentés aux quatre coins du monde, forment les étapes d’une vaste enquête sur le désir humain et sur la violence sacrificielle où toute société, selon Girard, trouve son origine inavouable.

Fondateur de la « théorie mimétique », ce franc-tireur de la scène intellectuelle avait bâti une œuvre originale, qui conjugue réflexion savante et prédication chrétienne. Ses livres, commentés aux quatre coins du monde, forment les étapes d’une vaste enquête sur le désir humain et sur la violence sacrificielle où toute société, selon Girard, trouve son origine inavouable.

READ MORE: Le Monde, November 5, 2015

Dès demain, vendredi 6 novembre, France Culture bouleverse ses programmes et rend hommage dans Les Matins au philosophe et académicien français, René Girard, « éminent théoricien surnommé « le nouveau Darwin des sciences humaines ».

Entretiens inédits, rediffusions d’interviews à partir du vendredi 6 novembre et tout au long de la semaine prochaine.

Réécoutez La Grande Table du 5 novembre : hommage à René Girard

Dossier spécial sur franceculture.fr :«Mort de l’anthropologue et philosophe René Girard»

READ MORE & LISTEN TO: France Culture, November 5, 2015

Quand, à 18 ans, Jean-Marc Bastière entre dans une librairie et tombe sur un livre de René Girard “des choses cachées depuis la fondation du monde”, après quelques pages, c’est comme si la foudre lui était tombé dessus. “Une révélation sur la nature humaine” nous dit-il, “une révélation sur l’humanité parce que je trouvais que ce qu’il disait, était limpide”. Chez Jean-Claude Guillebaud, ami de longue date de l’académicien, c’est un retour dans la religion qui l’a marqué: “je lui dois d’être revenu à la foi chrétienne. Je faisais partie de la génération des soixante-huitards , plus ou moins sécularisé comme beaucoup de jeunes de mon âge”. Progressivement en lisant ces livres, Jean-Claude Guillebaud prend conscience de la pertinence du message évangélique et “redevient chrétien”. D’ailleurs Jean-Marc Bastière retient la même chose, un accomplissement de la pensée, qu’il a pu approfondir et qui, aujourd’hui, est arrivé à maturité.

A écouter : René Girard dans notre émission Face aux chrétiens.

READ MORE & LISTEN TO: RADIO NOTRE DAME, November 5, 2015

In de Verenigde Staten is de Franse antropoloog en literatuurwetenschapper René Girard overleden. De Frans-Amerikaanse intellectueel wordt gezien als een van de grootste denkers van de voorbije 100 jaar. Hij schreef over de menselijke begeerte en was de ontdekker van het zondebokmechanisme als het verborgen fundament van religie en maatschappij. Cultuur, godsdienst en geweld staan centraal in zijn werk.

READ MORE: VRT Nieuws, deredactie.be, November 5, 2015

René Girard geldt als een van de belangrijkste denkers over de menselijke cultuur en godsdienstgeschiedenis van zijn generatie. Zijn reputatie vestigde hij met zijn even bejubelde als omstreden studie God en geweld. Elke cultuur gaat uiteindelijk terug op een gewelddaad, zo betoogde hij, en wordt juist cultuur doordat ze dat geweld weet te beteugelen. Het was een klap in het gezicht van ieder die meende dat de (moderne) beschaving juist tegenover het geweld en de religie staat, in plaats van eruit te zijn ontstaan.

READ MORE: NRC Handelsblad, November 5, 2015

La obra de Girard parte del campo de la historia, pero se mueve siempre de forma transversal entre la antropología, la filosofía y la literatura. Parte de una noción central: la de “mímesis” o imitación, que él toma directamente de Platón y Aristóteles para reconducirla en la elaboración de una concepción del hombre que encuentra refrendada tanto en la literatura como en la historia (la pasada y la presente).

READ MORE: El País, November, 5, 2015

Nascido no dia de Natal de 1923, em Avignon, René Girard escreveu bastante sobre a diversidade e unidade das religiões.

René Girard viva nos Estados Unidos desde 1947. Ensinou em várias universidades, como Duke, Johns Hopkins e, sobretudo, Stanford, onde dirigiu durante muito tempo o departamento de língua, literatura e civilização francesa.

Terminou a sua carreira académica em Stanford em 1995.

READ MORE: RTP, November 5, 2015

O acadêmico francês René Girard, eminente teórico conhecido como “o novo Darwin das ciências humanas”, morreu nesta quarta-feira (4), aos 91 anos, nos Estados Unidos, anunciou a universidade de Stanford, onde lecionou durante muitos anos.

READ MORE: Globo, November 5, 2015

Zum Tod des Kulturanthropologen René Girard – Wolfgang Palaver im Gespräch

LISTEN TO: ARD Mediathek, Deutschlandfunk, November 5, 2015

Vielfach ausgezeichnet, war Girard nach seiner Aufnahme in die Académie Française „unsterblich“. Seine Bücher werden bleiben – als Deutungsschema und Zündstoff im Zwillingskonflikt der Religionen, zwischen denen er keine Gleichheit ausmachen konnte.

READ MORE: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, November 5, 2015

READ MORE: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, November 5, 2015

Dank Figuren wie ihm hatten die Gegenstimmen zur “French Theory” das letzte Wort. Es waren Stimmen, die sich als die des “Realen” verstanden, gegen jene der Generationsgenossen Lévi-Strauss, Foucault, Derrida, welche die Mythen, Religionen, literarischen Texte, philosophischen Systeme vor allem für struktural zerlegbare Produkte der Fantasie hielten. Der Philosoph, Anthropologe und Religionsforscher René Girard weigerte sich jedoch, den Trieb, den Mythos oder das Kunstwerk einfach als Strukturelement eines immanenten Bedeutungssystems aufzufassen. Er suchte die gesellschaftliche und psychologische Wirklichkeit dahinter.

READ MORE: Süddeutsche Zeitung, November 5, 2015

Der 1923 in Avignon geborene Girard war zu seinen Lebzeiten ein singulärer kulturgeschichtlicher Denker. Aus seinem umfangreichen Werk sticht vor allem seine “Mimetische Theorie” und der “Sündenbockmechanismus” hervor.

Girard erklärt damit den Zusammenhang zwischen menschlichem Zusammenleben, der Entstehung von Gewalt und ihrer Eindämmung durch Religion, Tabus und Verbote. René Girard analysiert die menschliche Kultur und Geschichte aus der Perspektive der Gewaltentstehung und ihrer Opfer.

READ MORE & LISTEN TO: Österreichischer Rundfunk, November 5, 2015

Denn so subtil seine Beschreibung sozialer Phänomene ausfiel, so obsessiv versuchte er, sie für seine Zwecke, die Apologie der Religion, zu instrumentalisieren. Deshalb wirken seine Befunde manchmal überraschend und überzeugend, manchmal aber auch erzwungen.

Girards ganzes Werk ist eine Polemik gegen den Wunschtraum von der «rationalistischen Unschuld» der Moderne. Dass dieser Wunschtraum heutzutage tatsächlich ausgeträumt ist, ist nicht wirklich Girards Verdienst, aber Grund genug, sein Werk als Wegzehrung auf die Reise der Menschheit nach dem Ende der Unschuld mitzunehmen.

READ MORE: Neue Zürcher Zeitung, November 5, 2015

Academicianul francez Rene Girard, un eminent teoretician supranumit “noul Darwin al stiintelor umaniste”, a incetat din viata miercuri, la varsta de 91 de ani, in Statele Unite, a anuntat universitatea Stanford unde acesta a predat pentru o lunga perioada de timp, transmite AFP.

“Renumitul profesor francez de la Stanford, unul dintre cei 40 de nemuritori ai prestigioase Academii Franceze, a decedat in casa sa de la Stanford miercuri, dupa o indelungata boala”, a declarat universitatea californiana intr-un comunicat de presa.

Rene Girard si-a inceput cariera ca teoretician literar, fascinat de toate stiintele sociale: istorie, antropologie, sociologie, filosofie, religie, psihologie si teologie.

READ MORE: HotNews.ro, November 5, 2015

Rođen 1923. u Avignonu , kršćanin Girard mnogo je pisao o raznolikosti, ali i univerzalnosti religija, a svoju je misao crpio iz vjerskih tekstova i velikih književnih klasika.

READ MORE: SEEbiz, November 5, 2015

Girard’s extensive oeuvre has generated a wide range of responses across many disciplines, not least within Christian theology.

In 2005, on his election to L’Académie française, Girard was acclaimed by Michel Serres as the “Charles Darwin of the human sciences.” The post-modern intelligentsia – deeply wedded to the dogma of culture’s irreducible plurality – remains sceptical, also despising any attempted rehabilitation for the Queen of the Sciences.

Girard, with a dash of Gallic insouciance, referred to his critics’ small intellectual ambitions as “the comprehensive unionization of failure” – and of course his theory gives a good account of such academic rivalry, as well as the individualist’s refusal of personal conversion that acceptance of his theory demands.

Unsatisfied with uncovering the origin of culture and explicating the emergence of secular modernity, however, Girard came eventually to predict the apocalyptic acceleration of history towards a tragic denouement.

As for Rene Girard himself, he was an observant Catholic layman for 55 years and he knew that God’s Kingdom was not of this world. He looked forward to union with God, and there in faith and hope we leave him, where all the victims of history are vindicated and every tear is wiped away.

READ MORE: ABC, Australia, November 5, 2015

René Girard visited the UK on three occasions and was grateful to the Jesuits in Britain for the welcome he received here. His first visit was to Oxford, where stayed at Campion Hall and where he delivered the D’Arcy Lecture to 200 people in the university. This was followed by two visits to Heythrop, the second of which was to receive an honorary doctorate, as he was on his way to Paris to be received into the Académie française as one of their 40 immortels.

At times he was like an evangelical about his insights, but he was also capable of being playful, even offhand: ‘People are against my theory, because it is at the same time an avant-garde and a Christian theory … Theories are expendable. They should be criticized. When people tell me my work is too systematic, I say, I make it as systematic as possible for you to be able to prove it wrong.’

READ MORE: Jesuits in Britain, November 5, 2015

The following tribute is adapted in part from the forthcoming book Raising the Ante: God’s Gamble by Gil Bailie, a long-time friend and student of René Girard.

READ MORE: Catholic World Report, November 5, 2015

A társadalomtudományok új Darwinjaként méltatták, amikor a múlt század ’70-es éveiben kifejtette civilizációelméletét.

Életének 92. évében elhunyt René Girard francia tudós, aki a mimetikus vágyelmélet, a bűnbakképzés és a bibliamagyarázat terén megfogalmazott elméleteivel újfajta antropológiát alapozott meg. Kora egyik legjelentősebb gondolkodójaként, a társadalomtudományok új Darwinjaként emlegették. A Francia Akadémia tagja hosszan tartó betegség után szerdán hunyt el az Egyesült Államokban, halálhírét a Stanford Egyetem közölte. A francia gondolkodó hosszú ideig tanított a neves intézményben.

„Látám a sátánt, mint a villámlást lehullani az égből.” E könyvében a kereszténység kritikai apológiáját nem teológiai alapokon, hanem racionális bizonyítások útján írja meg. Valójában a zsidó-keresztény vallási tradíció rendkívül eredeti antropológiáját tárja az olvasó elé, magáévá téve Simone Weil egyik gondolatát, miszerint az Evangéliumok mindenekelőtt egy „emberelméletet”, egy antropológiát tartalmaznak, és csak ez után tekintendők „Istenelméletnek”, teológiának.

READ MORE: 24.hu, November 5, 2015

Un pensiero potentemente originale, quello dell’antropologo accademico di Francia che ha inventato — nel senso etimologico di “scoprire” — teorie illuminanti come il desiderio mimetico e il rito del capro espiatorio, perché non nato da schemi speculativi astratti, ma dall’osservazione dei meccanismi interiori che muovono quell’animale strutturalmente sociale che è l’uomo. L’essere umano di ogni epoca, non nel migliore dei mondi possibili ma nel mondo reale, dove si soffre e si muore per mano dei propri simili, vittime a loro volta — spesso inconsapevoli — di un automatismo interiore che li trasforma in carnefici certi di essere nel giusto e di obbedire a un dovere morale. Un pensiero letteralmente vicino all’origine, quello del «Darwin dell’antropologia», come lo chiamano in Francia, e quindi capace di illuminare anche i recessi più oscuri di quel mistero che chiamiamo genericamente coscienza, una chiave di lettura semplice e geniale allo stesso tempo scaturita più dalla lettura attenta dei capolavori di Proust, Dostoevskij, Dante e Cervantes che dalle pagine dei manuali di filosofia.

Un pensiero potentemente originale, quello dell’antropologo accademico di Francia che ha inventato — nel senso etimologico di “scoprire” — teorie illuminanti come il desiderio mimetico e il rito del capro espiatorio, perché non nato da schemi speculativi astratti, ma dall’osservazione dei meccanismi interiori che muovono quell’animale strutturalmente sociale che è l’uomo. L’essere umano di ogni epoca, non nel migliore dei mondi possibili ma nel mondo reale, dove si soffre e si muore per mano dei propri simili, vittime a loro volta — spesso inconsapevoli — di un automatismo interiore che li trasforma in carnefici certi di essere nel giusto e di obbedire a un dovere morale. Un pensiero letteralmente vicino all’origine, quello del «Darwin dell’antropologia», come lo chiamano in Francia, e quindi capace di illuminare anche i recessi più oscuri di quel mistero che chiamiamo genericamente coscienza, una chiave di lettura semplice e geniale allo stesso tempo scaturita più dalla lettura attenta dei capolavori di Proust, Dostoevskij, Dante e Cervantes che dalle pagine dei manuali di filosofia.

Un pensiero tanto celebrato quanto contestato, quello dell’antropologo francese che ha continuato a lavorare e a scrivere anche dopo aver superato i novant’anni, capace di anticipare successive scoperte scientifiche.

READ MORE: L’Osservatore Romano, November 5, 2015

L’antropologo, 91 anni, è morto ieri a a Stanford, negli Stati Uniti. Fondatore della “teoria mimetica”, da anticonformista della scena intellettuale aveva costruito un lavoro originale, che unisce riflessione accademica e predicazione cristiana. I suoi libri, commentati in tutto il mondo, sono tappe di una importante indagine sul desiderio umano e sulla violenza sacrificale da cui qualsiasi società, secondo Girard, trova la sua origine vergognosa. In Italia i suoi libri sono pubblicati da Adelphi.

READ MORE: Rai News, November 5, 2015

Pour finir, je voudrais dire un mot des implications pour le lecteur d’une telle théorie. Devenir «girardien», ce n’est pas appartenir à une secte ; ce n’est pas tenir pour vrai tout ce que Girard a écrit; c’est d’abord se laisser aller à une «conversion» qui n’est pas d’ordre religieux, mais qui est un bouleversement du regard sur soi, une critique personnelle de son propre désir.

Pour comprendre à quel point la théorie de Girard est vraie, il faut avoir cheminé à rebours de son désir, non pas pour atteindre un illusoire «moi» authentique, mais au contraire pour aboutir à l’inexistence de ce moi, toujours déjà agi par des «désirs selon l’autre». La théorie mimétique est un dévoilement progressif dont le lecteur n’est jamais absent de ce qui se dévoile à lui. Elle menace l’existence du sujet que je croyais être. Elle s’attaque à ce que je croyais le plus original chez moi.

Il n’est pas un lecteur de Girard, même le plus convaincu, qui ne se soit dit à la lecture de Mensonge romantique et vérité romanesque : «Il a raison, tout ça est vrai. Heureusement que pour ma part j’y échappe en partie.» Il serait suicidaire de ne se lire soi-même qu’avec les lunettes girardiennes ; on a besoin de croire un minimum aux raisons que notre désir se donne ; ces raisons constituent toujours une résistance en nous à la théorie mimétique, plus ou moins grande selon les individus. Il ne s’agit pas de s’en défendre, mais de le savoir. La lecture de Girard nous impose donc un double processus de révélation : on se rend compte d’abord que notre propre désir obéit aux lois décelées par Girard ; et dans un second temps, on se rend compte qu’on a feint l’adhésion totale à ses thèses, et qu’il reste en nous un moi «néo-romantique» qui ne se croit pas concerné par ces lois. Ainsi, la découverte de Girard doit nous interdire, in fine, le surplomb de celui qui aurait compris, contre tous ceux qui seraient encore des croyants naïfs en l’autonomie de leur désir.

READ MORE: Causeur.fr, November 5, 2015

Largement traduite, souvent admirée hors de son pays, comme aux Etats-Unis ou en Italie, l’oeuvre de René Girard reste assez mal connue du grand public en France. «Pour un intellectuel qui a longtemps été considéré comme un auteur à contre-courant et atypique, l’élection à l’Académie est une forme de reconnaissance», déclarait-il au quotidien La Croix le 15 décembre 2005, jour de sa réception à l’Académie française.

«Je peux dire sans exagération que, pendant un demi-siècle, la seule institution française qui m’ait persuadé que je n’étais pas oublié en France, dans mon propre pays, en tant que chercheur et en tant que penseur, c’est l’Académie française.»

READ MORE & WATCH: Le Parisien, November 5, 2015

Je me souviendrai toute ma vie de ce jour où mon ami François et moi, nous nous sommes annoncés chez lui dans le VIIème. Il avait la gentillesse de nous recevoir alors qu’il était au milieu de sa famille. Il nous parlait. O temps suspends ton vol. Le monde familier qui l’entourait n’existait plus pour lui. Cette longue conversation qui n’était pas la première, m’a beaucoup fait réfléchir sur le mal. François, passionné de Thomas d’Aquin, trouvait Girard pessimiste. Quant à moi, j’ai décidé ce jour-là de remonter, avec Girard, de saint Thomas à saint Augustin.

Girard est-il pessimiste? Il le serait, il serait gnostique si l’on découvrait dans son oeuvre un refus quelconque de la chair et de la condition charnelle de l’homme. C’est tout le contraire. Le désir charnel n’intéresse pas Girard comme il intéresse Freud, parce que Girard le méridional sait très bien ce que Freud ne sait pas : le désir n’est pas une production physique de l’animal humain mais une construction psychique.

“For me he completely undid the secular Enlightenment’s undoing of Christianity.” (Sean O’Conaill).

READ MORE: acireland, November 5, 2015

Comprendere «nello stesso momento, perché i credenti dapprima, e sul loro esempio i non credenti poi, sono sempre passati vicino al segreto, peraltro così semplice, di ogni mitologia»: è stata questa l’ambizione e l’esito della ricerca del francese René Girard, che si è spento a Stanford, negli Stati Uniti. Una ricerca che era impossibile (lo dimostra l’intervista autobiografica del 1994 con Michel Treguer) incasellare nei riquadri angusti delle discipline accademiche.

Da questa ricerca iniziata con Dostoevskij arriva l’opera che ne fa un filosofo e un antropologo della religione: La violenza e il sacro del 1972 (Adelphi, 1980) elabora una teoria della genesi della religione. Nella mitologia e nella sua elaborazione filosofica e letteraria Girard ritrova l’atto iniziale di occultamento che «inganna la violenza»: il «sacro» che assorbe la violenza destinata fatalmente a nascere e la riversa su una entità non vendicabile e insieme in apparente continuità con coloro al posto dei quali viene sacrificato. Così il capro espiatorio placa e fonda la società in questa ombra religiosa che è «il sentimento che la collettività ispira ai suoi membri, ma proiettato fuori dalle coscienze che lo provano, e oggettivato».

READ MORE: Corriere della Sera, November 6, 2015

Jean-Pierre Elkabbach et Europe 1 ont souhaité rendre hommage à l’académicien et philosophe René Girard disparu à l’âge de 91 ans.

WATCH & LISTEN TO: Europe 1, Crif, November 6, 2015

Difficilement «classable» dans une pensée ou l’autre, René Girard a toujours affiché sa foi chrétienne malgré les critiques d’une partie de la communauté scientifique. Il s’est ainsi beaucoup penché sur l’origine et le devenir des religions, jusqu’à leurs formes extrémistes d’aujourd’hui.

Ce sont d’ailleurs ses recherches sur la Bible qui l’ont conduit à la foi chrétienne, comme l’explique à Anne-Sophie Saint-Martin le théologien jésuite Dominique Peccoud.

READ MORE & LISTEN TO: Radio Vatican, November 6, 2015

In his 1950s poem “Vespers,” W. H. Auden recalls a meeting of representatives of two different political standpoints. They come together:

to remind the other (do both, at bottom, desire truth?) of that half

of their secret which he would most like to forget,

forcing us both, for a fraction of a second, to remember our victim

(but for him I could forget the blood, but for me he could forget

the innocence),

on whose immolation (call him Abel, Remus, whom you will, it is

one Sin Offering) arcadias, utopias, our dear old bag of a democracy

are alike founded:

For without a cement of blood (it must be human, it must be

innocent) no secular wall can safely stand

Nobody familiar with René Girard’s mimetic theory can read this poem and not think somehow that Auden “got it.” Girard himself never discussed this poem, but argued convincingly that so many of the greatest literary giants—Proust, Dostoevsky, Freud, Shakespeare, Sophocles, the evangelists, the Psalmist—got it, or very nearly got it. Girard’s doggedness led him on a wild intellectual journey from the great novelists to Greek tragedy, from biblical texts to the writings of Freud and Nietzsche. He devoted his final book to the thought of a Prussian military historian, Carl Clausewitz.

Even in taking full measure of Girard’s impact on the human and social sciences, it seems silly to label Girard a “genius.” Besides being a Romantic descriptive that Girard would have certainly abhorred, such a moniker ignores the fact that Girard’s great insight was not his at all. His primary talent was to notice how others captured the mimetic quality of human desire, and the consequences of this peculiarly human way of desiring.

There is an Ignatian quality to mimetic theory. Mimetic forces operated loudly in the life of St. Ignatius, and his “Exercises” and contemplative practices seem geared to helping us gain awareness of the undercurrents that otherwise manhandle us. This explains to some extent why the first theologian to discover Girard was a Jesuit—Raymund Schwager—and why Henri de Lubac, perhaps the greatest Jesuit theologian of the past century, read Girard and assured him that nothing in his thought could not be reconciled with orthodox Christianity.

READ MORE: America Magazine, November 6, 2015

Girard is a thinker who combined an utter lack of self-importance with the boldest intellectual risk-taking. A Stanford colleague, Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, declares that Girard is:

“a great, towering figure – no ostentatiousness. … Despite the intellectual structures built around him, he’s a solitaire. His work has a steel-like quality– strong, contoured, clear. It’s like a rock. It will be there and it will last.”

READ MORE: Thinking Faith, November 6, 2015

Typiquement, le girardien sans christianisme, cet oxymoron qui prolifère aujourd’hui, s’efforce de découvrir la violence, les boucs émissaires et le ressentiment partout, sauf là où cela ferait vraiment une différence, la seule différence qui tienne, c’est-à-dire en lui-même. C’est ainsi que les bien-pensants passent leur temps à dénoncer le racisme dégoutant du bas-peuple de France sans paraître voir le racisme de classe dont ils font preuve à cette occasion. Ce girardisme sans christianisme est le pire des contresens d’un monde qui pourtant n’en est pas avare: le monde post-moderne est plein de concepts girardiens devenus fous.

READ MORE: Causeur.fr, November 6, 2015

«Existen graves malentendidos en lo que concierne a mi trabajo. A menudo se ve en mí un reaccionario o, al contrario, del lado de los cristianos, una especie de herético utopista.» (René Girard).

«Existen graves malentendidos en lo que concierne a mi trabajo. A menudo se ve en mí un reaccionario o, al contrario, del lado de los cristianos, una especie de herético utopista.» (René Girard).

Podrá estarse de acuerdo o no con muchas de las propuestas de Girard, podrá surgir cierto empalago entre sus lectores (me incluyo entre ellos), mas lo que no puede negarse es su capacidad de provocar pensamiento, de atravesar diferentes campos del saber y comportarse, tras su pista como, un cazador furtivo que penetra en campos inesperados y que en principio parecen acotados para otros acercamientos. Llegados a este punto no queda más que desear al pensador desaparecido, verdadero agitador del campo del pensamiento … que la terre vous soit légère.

READ MORE: Kaosenlared, November 6, 2015

Quelle est la nature du désir humain? Quelle est l’origine de la violence? Comment naissent les religions? Qu’est-ce qu’une culture? Ce ne sont là que quelque unes des questions fondamentales auxquelles les travaux de l’anthropologue français René Girard, décédé le 04 novembre à l’âge de 91 ans, permettent de répondre.

Considéré à juste titre comme l’un des penseurs majeurs de la seconde partie du XXième siècle, il était parfois surnommé depuis le début du troisième millénaire « le Darwin des sciences humaines ». Une reconnaissance tardive pour celui qui publia son premier ouvrage en 1961 – Mensonge romantique et vérité romanesque, devenu un classique – mais qui donne une idée de l’ampleur de l’apport girardien au savoir universel.

Comme le naturaliste anglais, René Girard est un penseur des origines. Sa découverte de la nature mimétique du désir et des mécanismes de désignation et de meurtres de boucs émissaires qui en découlent, partage avec la notion darwinienne d’évolution une simplicité explicative à l’efficacité redoutable, pour ne pas dire incontestable.

Mais il y a une différence entre les deux penseurs. Alors que les découvertes de Charles Darwin l’amenèrent à perdre la foi, c’est en comparant des mythes du monde entier avec la Bible que René Girard renoua avec une foi qu’il avait passablement oubliée.

READ MORE: Atlantico, November 7, 2015

De mens heeft, zoals we weten, de geheimzinnige neiging om te gaan lijken op zijn tegenstander. De religieus geïnspireerde oorlogsretoriek van George Bush was op den duur niet meer van die van Osama bin Laden te onderscheiden. Vijanden bestuderen elkaar zo diepgaand, dat ze elkaar gaan nabootsen. De filosoof en religiewetenschapper die daar veel over heeft geschreven, René Girard, overleed deze week op 91-jarige leeftijd. Zijn werk heeft het denken over begeerte, geweld en rivaliteit veranderd.

De mens heeft, zoals we weten, de geheimzinnige neiging om te gaan lijken op zijn tegenstander. De religieus geïnspireerde oorlogsretoriek van George Bush was op den duur niet meer van die van Osama bin Laden te onderscheiden. Vijanden bestuderen elkaar zo diepgaand, dat ze elkaar gaan nabootsen. De filosoof en religiewetenschapper die daar veel over heeft geschreven, René Girard, overleed deze week op 91-jarige leeftijd. Zijn werk heeft het denken over begeerte, geweld en rivaliteit veranderd.

Een variant op deze nabootsing tussen vijanden doet zich voor bij betogers tegen vluchtelingenopvang. Zo beducht zijn de betogers voor verkrachting, geweld en maatschappelijke ontwrichting door vluchtelingen, dat zij andersdenkenden verkrachting toewensen, geweld toepassen en maatschappelijke ontwrichting veroorzaken.

READ MORE: Column Tommy Wieringa, Provinciale Zeeuwse Courant, November 7, 2015

“Die Rivalität spielt eine so gewaltige Rolle, daß man den Versuch, die Nachahmung auszutreiben, vergeblich unternimmt.”

Der Verfasser dieser so rabiat richtigen Sätze ist am vergangen Mittwoch in Stanford knapp 92jährig verstorben. René Girard, der Bibeltreueste aller französischen Denker, erreichte ein biblisches Alter.

READ MORE: artmagazine, November 7, 2015

The publishing world says that the title to be called a “bestselling book” rather than an advertisement gives stronger motivation for Korean readers to purchase the book. When best-selling products sell more, we call it the theory of social evidence in social psychology.

“Following what others do” is particularly evident in Korea. Imitating others’ preference and desire, however, is one of the features of modern society. That’s why TV commercials prod consumers’ desire to buy products by showing a rice cooker that Kim Soo-hyeon uses and beer that Jun Ji-hyun drinks. René Girard (1923-2015), French philosopher who died in the U.S. on Wednesday, formulated the structure of human being’s desire into the theory of “triangular desire.”

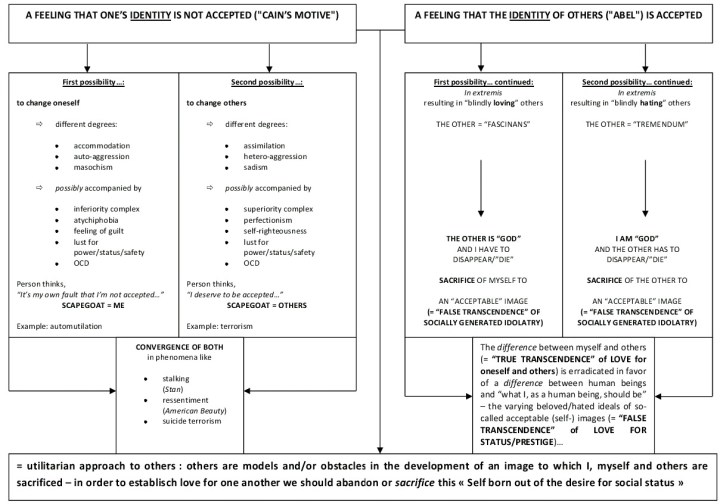

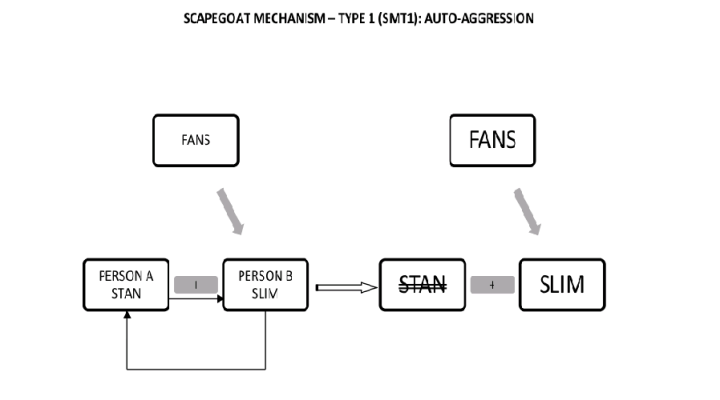

In many cases, the coercion by parents who push their kids to become a doctor or a lawyer regardless of their aptitude derives from “mimetic desire.” The triangular desire can be dreadful in that people are not aware of the fact that they live their lives mimicking others. Girard says that the mankind competes each other to mimic other’s desire and creates collective stress such as jealousy and animosity that is relieved in a wrong manner by using socially marginalized people as scapegoats. Peeping into the desire of others through social network service has become a daily routine. Now, we need to practice not to be swayed by the desire that “seems to be mine, but is not mine, still looks like mine” just like a line of a popular song.

출판시장에선 잊을만하면 사재기 베스트셀러 순위 조작 논란이 불거진다. 편법을 써서라도 베스트셀러 순위에 오르면 판매실적이 올라간다는 믿음 때문이다. 출판계에 따르면 국내 독자의 구매 욕구를 자극하는 건 광고보다 베스트셀러 타이틀이다. 가장 많이 팔린 상품이 더 많이 팔리는 현상을 사회심리학에서는 사회적 증거의 법칙이라고 부른다.

한국사회에서 유독 남들 따라하기와 쏠림현상이 심하기는 하지만 타인의 취향과 욕망을 모방하는 것은 현대 사회의 특징이다. TV 광고에서 김수현이 쓰는 밥솥과 전지현이 마시는 맥주를 보여주며 대중의 소비 욕망을 자극하는 것도 그 때문이다. 이 같은 인간 욕망의 구조를 욕망의 삼각형 이론으로 체계화한 프랑스 사상가가 4일 미국서 별세한 르네 지라르(19232015)였다.

문학평론가에서 출발한 지라르는 철학 역사학 인류학 종교학 등을 두루 통섭하는 업적을 남겨 인문학의 새로운 다윈으로 평가받는다. 미국에서 반세기 넘게 살았음에도 2005년 불멸의 40인으로 불리며 국민의 존경을 받는 프랑스 아카데미 프랑세즈의 정회원이 됐다. 그는 소설 분석을 통해 우리가 원하는 것이 실은 남의 욕망을 베낀 것에 지나지 않는다는 결론을 내렸다. 예컨대 보바리 부인에서 상류사회를 동경하는 엠마의 욕망은 자연발생적인 것이 아니다. 단지, 사춘기 때 읽은 삼류 소설 주인공의 욕망을 본뜬 것이다.

부모가 자녀 적성에 관계없이 의시나 변호사가 되라고 강요하는 것도 모방욕망에서 비롯된 경우가 많다. 욕망의 삼각형이 무서운 이유는 자신이 남의 욕망을 모방하며 살고 있다는 사실 자체를 자각하지 못하는 것이다. 지라르에 따르면 인류는 경쟁적으로 남의 욕망을 모방하다 쌓여가는 질투 적개심 같은 집단적 스트레스를 사회의 소외된 사람을 엉뚱한 희생양으로 삼아 해소한다. 소셜네트워크서비스(SNS)를 통해 남의 욕망을 엿보는 게 일상이 돼버렸다. 유행가 가사에 나오듯 내 것인 듯 내 것 아닌 내 것 같은 욕망에 휘둘리지 않는 연습이 필요한 시대다.

READ MORE: The Dong-A Ilbo, November 7, 2015

In 2001, my spiritual mentor Bob Holum gave me a book that completely changed everything for me: Rene Girard’s Things Hidden Since the Foundation of This World. I learned the sad news that Girard died this past week, so I wanted to reflect on how his ideas helped Jesus’ cross and the Christian gospel make a lot more sense to me.

READ MORE: Patheos, November 7, 2015

Many Christians have not yet caught up with his scholarship on these themes, disclosing not so much new ideas but original themes often hidden. The life, teaching and death of Jesus are shown to continue the work of unraveling human violence and scapegoating and to reveal the divine as the source of creative love unfolding through history and culture. His work is not an easy read but many other scholars, authors and teachers are making his work accessible. Thank you René!

READ MORE: Modern Church, November 7, 2015

For Girard, one summary view might have it, at the very beginning it is not religion that leads to violence, but violence which leads to—which indeed creates a need for—religion, as a way of channeling and constraining the use of force. But once the process starts, religion can of course fuel violence, as Girard could see. You don’t have to be one of his devotees to observe that scapegoating as a form of team-building has taken many different forms, from the Salem witch-trials to the anti-communist hysteria of 1950s America to ritual denunciations of erstwhile comrades by the Soviet Politburo. But there is something particularly vicious and destructive about a religiously inspired lynch mob whose blood is up, and has somehow been convinced that its own salvation (and internal cohesion) lies in annihilating the heretic or the infidel. At the very minimum, Girard’s work is a help in understanding how religions (Christianity in particular, but perhaps also Buddhism) can be pacifist in content but often violent and bullying in historical practice. Think of the mobs that rampaged through Jewish quarters in European cities during the Middle Ages, especially in Holy Week. At a time when Christians were supposed to be identifying with a victim of scapegoating, they perpetrated that very thing.

READ MORE: The Economist, November 7, 2015

Mercredi 4 novembre, René Girard a rejoint le ciel de la vérité romanesque en compagnie des grands romanciers qui lui ont donné à penser sa théorie du désir mimétique. L’occasion de revenir sur les essais et les concepts qui ont jalonné sa carrière intellectuelle iconoclaste.

Avec son premier essai paru en 1961, Mensonge romantique et vérité romanesque, Girard approfondit les grands textes de Don Quichotte à L’Éternel mari, au point d’élaborer une clef de lecture qui dépasse le strict cadre de la littérature. Grâce à une analyse comparée des classiques, il remarque que Dostoïevski, Flaubert, Stendhal ou Proust, surmontent tous un passage romantique pour embrasser une vérité romanesque. L’épreuve romanesque d’un Julien Sorel, celle d’une Emma Bovary, rappellent combien nous ne sommes jamais seuls avec nos désirs les plus intimes.

Scandale pour les structuralistes de l’époque qui ne lui pardonneront pas une lecture thématique ouverte à la psychanalyse, l’essai accouche d’une théorie décisive pour les sciences humaines. Un tiers est toujours là, qu’il soit rival ou modèle souverain, à l’origine de toutes nos actions. Avec son mythe individualiste qui nous veut maîtres de nos propres désirs, la littérature romantique participe à cacher cette vérité dérangeante. Pourtant, si Madame Bovary trompe son médiocre mari et noie son ennui dans des romans à l’eau de rose, elle imite, fascinée, ses lectures qui l’invitent à l’évasion sentimentale. Tous les grands romanciers ont conscience de ces modèles qui hantent leurs personnages en situation de crise, souvent dans le sang et les larmes.

READ MORE: Philitt, November 7, 2015

Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung, November 8, 2015:

Acaba de fallecer (4.XI.2015) en Estados Unidos, donde vivía y enseñaba desde hace unos decenios, el mayor de los antropólogos y quizá de los pensadores cristianos de la segunda mitad del siglo XX.

R. Girard ha repensado y ha querido superar la visión del hombre que ofrecen Marx y Freud, con una teoría abarcadora (universal) que permite integrar (interpretar y recrear) los temas radicales de la conciencia individual y social, con la mímesis, la lucha mutua y violencia.

Su investigación crítica (hipotética en algunos puntos) resulta necesaria para entender algunos de los temas más significativos de nuestra cultura, como son la violencia y el victimismo o, mejor dicho, la existencia de las víctimas, primero asesinadas y después manipuladas por los mismos asesinos.

Todos los políticos que yo conozco hablan de la importancia de las víctimas, quizá sin saber que ese lenguaje se lo deben a Girard, aunque no hayan entendido lo que él quiere decir…, aunque no aceptarían muchas de sus propuestas.

A los ojos de Girard, la crítica de Nietzche en contra de la religión resulta más aguda que la de Marx, pues él ha puesto de relieve unos mecanismos de proyección reactiva de los oprimidos que tienden a satanizar a los triunfadores, haciendo de la religión un principio de venganza. Pero tampoco Nietzsche ha llegado hasta el fondo del problema, pues su filosofía sigue presa en los esquemas o mecanismos del chivo expiatorio.

READ MORE: Salamanca RTV, November 8, 2015

Larga vida a las obras magistrales de René Girard.

READ MORE: Milenio, November 8, 2015

A veces digo que Girard me salvó la vida. Yo andaba por esa época obsesionadísimo con las aristas fascinantes y suicidas del hombre del subsuelo de Dostoievski: Raskolnikov y su forma demente de ver el mundo, trastornado por una rabia insondable. Si no llego a leer esa primavera su análisis crítico y clarividente de las pulsiones subsuelíticas, difícilmente habría llegado a la treintena. Todavía hay gente que hoy me considera un exaltado, pero lo de ahora no es nada comparado con esa época.

READ MORE: El Mundo, November 9, 2015

Sous les couronnes, on tend à passer sous silence qu’on l’a fortement critiqué, car il dérangeait les philosophes marxistes et qu’il portait un éclairage différent sur l’anthropologie structuraliste. De plus, son analyse du phénomène religieux était considérée comme superflue à une époque où l’on prétendait que “Dieu était mort”.

Les intellectuels français, plutôt que de débattre, ont préféré exclure. C’est ainsi qu’un des penseurs les plus reconnus mondialement est décédé à Los Angeles.

READ MORE: Les Echos, November 10, 2015

‘जमाव कधीच निरपराध नसतो. सामूहिक हिंसाचार हा खोटारडेपणाच्या आड दडलेला असतो’, हे विधान फ्रेंच विचारवंत आणि मानव्यसंशोधक रेने गिरार्ड यांनी येशूच्या सुळी जाण्यासंदर्भात केले होते खरे, पण ते कोणत्याही देशातील/ काळातील सामूहिक हिंसाचाराला लागू पडावे. गिरार्ड यांचे निधन गेल्या आठवडय़ात, वयाच्या ९२ व्या वर्षी झाले आणि जगाने तत्त्वचिंतक- अभ्यासक गमावला. युद्ध, हिंसाचार आणि ‘संस्कृती’ यांच्या संबंधांचा अभ्यास करताना वाङ्मय, तत्त्वज्ञान, मानसशास्त्र, इतिहास यांचा आंतरशाखीय विचार करून त्यांनी ‘बळीचा सिद्धान्त’ मांडला होता. या अनुषंगाने, ‘आपल्या इच्छा आपल्या नसतात’ (मानवी अनुकरणाचा सिद्धान्त) आणि अनुकरण करता येत नाही म्हणून- किंवा दुसऱ्याकडे आहे ते आपल्याकडे नाही म्हणून संघर्ष/ हिंसाचार, कारणाचे सुलभीकरण करून निरपराधांना नाडण्याची प्रवृत्ती.. अशी सत्ये त्यांनी साधार मांडली. चार्ल्स डार्विनचा नैसर्गिक निवडीचा सिद्धान्त हा मानवी संस्कृतीत टिकून राहिलेल्या बहुविधतेलाही लागू आहे असे सांगणारे गिरार्ड ‘मानव्यविद्यांमधील डार्विन’ म्हणून ओळखले जात.

READ MORE: Loksatta, November 10, 2015

Girard’s first book, Deceit, Desire and the Novel (1961 in French; 1965 in English), used Cervantes, Stendhal, Proust and Dostoevsky as case studies to develop his theory of mimesis. The Guardian recently compared the book to “putting on a pair of glasses and seeing the world come into focus. At its heart is an idea so simple, and yet so fundamental, that it seems incredible that no one had articulated it before.”

READ MORE: The Wire, November 10, 2015

Too few people know about René Girard, who passed away on Nov. 4 at 91. He was undoubtedly one of the most important men of the 20th century.

In the end, his country recognized him, giving him perhaps its highest honor for intellectuals of the humanities, a seat at the Académie Française.

Girard’s work, summed up under the heading “mimetic theory,” is like a flash of lightning on a dark summer night, suddenly illuminating everything in a strange new light. Girard’s thought has had an influence in fields as diverse as literary criticism, history, anthropology, philosophy, theology, psychology, economics, and even Silicon Valley entrepreneurship.

READ MORE: The Week, November 10, 2015

En Colombia vivimos un tanto crispados por la polarización entre posiciones extremas, que siempre tienden a descalificar al adversario. Así, el principal reto para la construcción de la paz es el cambio cultural. Algunos proponen aplicar técnicas de diverso orden, para aprender a gestionar los conflictos sin recurrir a la violencia; otros, incrementar el estado liberal de derecho y fortalecer el mercado, restringiendo el poder de la religión, considerada como causa del fanatismo que nos impide vivir en paz.

Con Girard, podríamos aprender cómo salirnos de los enredos que nos conducen a la violencia, tanto la cotidiana como la que enfrenta a diversos grupos y afecta dramáticamente a la sociedad. Y también podríamos aprender a ganar una distancia crítica frente a las posiciones que consideran que la paz significa más mercado y más Estado de derecho. Y lo haríamos al reconocer que estos son también sistemas constituidos sobre exclusiones y centrados en elementos incuestionables, que ocupan el lugar de lo sagrado primitivo; dicho brevemente, son sistemas religiosos.

Así, gracias a Girard podríamos volver a apreciar el valor de ese viejo libro, la Biblia, que nos expone los mecanismos religiosos, o sea, de violencia, que constituyen a las sociedades, al tiempo que nos invita a tomar distancia y a reflexionar en silencio.

READ MORE: El Tiempo, November 10, 2015

Mr. Thiel, of PayPal, said that he was a student at Stanford when he first encountered Professor Girard’s work, and that it later inspired him to quit an unfulfilling law career in New York and go to Silicon Valley.

Mr. Thiel, of PayPal, said that he was a student at Stanford when he first encountered Professor Girard’s work, and that it later inspired him to quit an unfulfilling law career in New York and go to Silicon Valley.

He gave Facebook its first $100,000 investment, he said, because he saw Professor Girard’s theories being validated in the concept of social media.

“Facebook first spread by word of mouth, and it’s about word of mouth, so it’s doubly mimetic,” he said. “Social media proved to be more important than it looked, because it’s about our natures.”

The investment made Mr. Thiel a billionaire.

A nonpracticing Roman Catholic, Professor Girard underwent a religious awakening after a cancer scare in 1959, while working on the conclusion of his first book.

“I was thrown for a loop, because I was proud of being a skeptic,” he later said. “It was very hard for me to imagine myself going to church, praying and so on. I was all puffed up, full of what the old catechisms used to call ‘human respect.’ ”

The Christian influence on his work was most apparent in “Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World,” written in 1978 and published in English in 1987. In that book he said Christianity was the only religion that had examined scapegoating and sacrifice from the victim’s point of view.

His final work, published in 2007, posited that the mimetic competition among nations would lead to an apocalyptic confrontation unless nations could learn to renounce retaliation.

That forthright religious stance may have cost him status in university circles, said Robert Pogue Harrison, a professor of literature at Stanford. “No doubt it was an obstacle,” he said. “He believed in Christian truth, which isn’t going to find ready acceptance in contemporary academia.”

Much recognition came to Professor Girard late in life. He was elected to the Académie Française in 2005 and received a lifetime achievement award from the Modern Language Association in 2009. In 2013 he received the Order of Isabella the Catholic from the king of Spain for his work in philosophy and anthropology.

READ MORE: The New York Times, November 10, 2015

Exclusif: un entretien inédit avec René Girard (1923-2015) réalisé en 2008 à l’université de Stanford.

READ MORE: Contrepoints, November 11, 2015

Han blev inte en tänkare på modet, men René Girards analyser av litteraturen lämnade ovärderliga bidrag till förståelsen av människan, skriver Anders Olsson.

Men med hjälp av de nycklar han haft till hands har han gett oss ovärderliga bidrag till förståelsen av människans fatala – eller underbara – bundenhet vid sin nästa. Med stort mod och stor envishet har han fått oss att se dolda mekanismer som formar och bryter ner kulturer och samhällen, men som vi har ytterst klena resurser att bemöta. Av sådant skapas uppenbarligen inga trender. Behovet ligger djupare, i den vilja till insikt som mödosamt och föga gloriöst söker upp det vi inte vill veta av.

READ MORE: Sydsvenskan, November 11, 2015

There are some thinkers that offer intriguing ideas and proposals, and there is a tiny handful of thinkers that manage to shake your world. Girard was in this second camp. In a series of books and articles, written across several decades, he proposed a social theory of extraordinary explanatory power.

In the second half of the twentieth century, academics tended to characterize Christianity – if they took it seriously at all – as one more iteration of the mythic story that can be found in practically every culture. From the Epic of Gilgamesh to Star Wars, the “mono-myth,” to use Joseph Campbell’s formula, is told over and again. What Girard saw was that this tired theorizing has it precisely wrong. In point of fact, Christianity is the revelation (the unveiling) of what the myths want to veil; it is the deconstruction of the mono-myth, not a reiteration of it-which is exactly why so many within academe want to domesticate and de-fang it.

The recovery of Christianity as revelation, as an unmasking of what all the other religions are saying, is René Girard’s permanent and unsettling contribution.

READ MORE: The Boston Pilot, November 11, 2015

Looking at patterns across historical cultures, Girard had noticed a the prevalence of “scapegoating” or ceremonially placing communal indiscretions onto one person. This is so prevalent today that our ears are likely deaf and eyes blind to it when it happens. A celebrity who kisses the nanny and divorces their spouse is, in some sense, hated all the more not because of what they did but because their behavior embodies “everything wrong with the world,” even our own longing for adventure. Girard’s unique perspective, focused through years of studying literature, mythology, and religious texts, saw scapegoating behavior as imitative or “mimetic.” That is, once the needs of survival are met, humans begin to develop wants that are shaped communally, in emulation of one another. This always leads to competition – indeed, competitive desire is the primary assumption of Western economics.

READ MORE: Huffington Post, November 11, 2015

MORE INTERESTING ARTICLES AND MORE MEDIA:

Obituary by Maria Clara Lucchetti Bingemer in Journal do Brasil

Radio Feature by Joe Gelonesi on ABC, Australia (with references on the passing of Rene Girard)

Interview with James Alison (Video) in America Media

Hommage for René Girard (Audio) by Raphaël Enthoven in franceculture

Article by Rodrigo Negrete in Nexos (Mexico)

Obituary by Antoine Lagadec in Revue des deux Mondes (France)

Obituary by Thomas Assheuer in Die Zeit (Germany)

Obituary by Józef Niewiadomski in Die Furche (Austria)

Obituary by Nelson Tepedino in Prodavinci (Venezuela)

Article by Roberto Ago in Artribune (Italy)

Obituary by Joseph Bottum in The Weekly Standard (USA)

Obituary by Suzanne Ross in Patheos

Obituary by Social Science Space

Obituary by Antoine Nouis and Jean-Luc Mouton in Réforme (France) – including a long interview with René Girard from 2008

Article by Michael Kirwan in Thinking Faith (UK)

Hommage René Girard (Video), École Normale Supérieure

Obituary SanatAtak (Turkey)

Obituary by Pierre-Yves Gomez in The Conversation (UK)

Obituary by Joanna Tokarska-Bakir in wyborcza.pl (Poland)

Obituary by Pier Giacomo Ghirardini in Tempi (Italy)

Article by Stéphane Ratti in Revue des deux Mondes (France)

Obituary by Alfio Squillaci in gliStatiGenerali (Italy)

Obituary by Roberto Calasso in Re Pubblica (Italy)

Article by Jean-Baptiste NOE in La Synthèse (France)

Article by The Raven Foundation: Many Voices in Celebration – a Tribute to René Girard

Article by Cynthia Haven, remembering today’s funeral (November 14, 2015) of René Girard and paying tribute to the victims of yesterday’s (November 13, 2015) terrorist attacks in Paris

RENÉ GIRARD, “THE EINSTEIN OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES” IN FORBES, NOV 30, 2015

READ ALSO: Killing Idols – Commemorating René Girard’s Spirituality

To conclude, this video interview by Daniel Lance:

The problem, of course, is that competing groups imitate this reasoning for their own particular group and thus reinforce the rivalry between each other (read René Girard’s Battling to the End in this regard, on mimetic rivalry on a planetary scale – highly recommended!).

The problem, of course, is that competing groups imitate this reasoning for their own particular group and thus reinforce the rivalry between each other (read René Girard’s Battling to the End in this regard, on mimetic rivalry on a planetary scale – highly recommended!). Not surprisingly, in light of mimetic theory, disobedience is more likely to occur:

Not surprisingly, in light of mimetic theory, disobedience is more likely to occur: People are motivated to explain their own and others’ behavior by attributing its causes to situation or disposition. Again, not surprisingly in light of mimetic theory, people show the tendency to overestimate personality factors in explaining the behavior of others, while they underestimate situational influence. On the other hand, the concept of self-serving bias points to the fact that people often do the opposite when explaining their own behavior: people try to justify themselves.

People are motivated to explain their own and others’ behavior by attributing its causes to situation or disposition. Again, not surprisingly in light of mimetic theory, people show the tendency to overestimate personality factors in explaining the behavior of others, while they underestimate situational influence. On the other hand, the concept of self-serving bias points to the fact that people often do the opposite when explaining their own behavior: people try to justify themselves. “us vs. them” social identities that are strengthened when groups compete (in-group vs. out-group; see Muzafer Sherif and his Robbers Cave experiment)

“us vs. them” social identities that are strengthened when groups compete (in-group vs. out-group; see Muzafer Sherif and his Robbers Cave experiment)

The mimetic building blocks of our psycho-social fabric are at once responsible for the preservation and disintegration of that very same fabric. One of the well-tried means to restore a social order that is in crisis because of escalating mimetic rivalry, is the so-called scapegoat mechanism. This restoration again rests on mimetic processes. Let’s turn to the example of the soccer team once more. When a team loses time and again, that’s normally no favorable factor for the group atmosphere. Teammates start blaming each other for bad results, maybe even sabotaging each other. There also might be ill-will towards the coach by players who feel they’re not given enough opportunities to play matches. And when the coach becomes part of the rivalry and frustrations within the team, that’s usually the end of his career there. As more players imitate the ill-will of some teammates towards their coach, the latter becomes the one held responsible for all the major problems within the team, and he’ll be fired by the board in the end. Instead of recognizing the mimetic origins of social disorder, people tend to blame one outsider or a group of outsiders. This scenario is well-known.

The mimetic building blocks of our psycho-social fabric are at once responsible for the preservation and disintegration of that very same fabric. One of the well-tried means to restore a social order that is in crisis because of escalating mimetic rivalry, is the so-called scapegoat mechanism. This restoration again rests on mimetic processes. Let’s turn to the example of the soccer team once more. When a team loses time and again, that’s normally no favorable factor for the group atmosphere. Teammates start blaming each other for bad results, maybe even sabotaging each other. There also might be ill-will towards the coach by players who feel they’re not given enough opportunities to play matches. And when the coach becomes part of the rivalry and frustrations within the team, that’s usually the end of his career there. As more players imitate the ill-will of some teammates towards their coach, the latter becomes the one held responsible for all the major problems within the team, and he’ll be fired by the board in the end. Instead of recognizing the mimetic origins of social disorder, people tend to blame one outsider or a group of outsiders. This scenario is well-known.

De mens heeft, zoals we weten, de geheimzinnige neiging om te gaan lijken op zijn tegenstander. De religieus geïnspireerde oorlogsretoriek van George Bush was op den duur niet meer van die van Osama bin Laden te onderscheiden. Vijanden bestuderen elkaar zo diepgaand, dat ze elkaar gaan nabootsen. De filosoof en religiewetenschapper die daar veel over heeft geschreven, René Girard, overleed deze week op 91-jarige leeftijd. Zijn werk heeft het denken over begeerte, geweld en rivaliteit veranderd.

De mens heeft, zoals we weten, de geheimzinnige neiging om te gaan lijken op zijn tegenstander. De religieus geïnspireerde oorlogsretoriek van George Bush was op den duur niet meer van die van Osama bin Laden te onderscheiden. Vijanden bestuderen elkaar zo diepgaand, dat ze elkaar gaan nabootsen. De filosoof en religiewetenschapper die daar veel over heeft geschreven, René Girard, overleed deze week op 91-jarige leeftijd. Zijn werk heeft het denken over begeerte, geweld en rivaliteit veranderd.

Mr. Thiel, of PayPal, said that he was a student at Stanford when he first encountered Professor Girard’s work, and that it later inspired him to quit an unfulfilling law career in New York and go to Silicon Valley.

Mr. Thiel, of PayPal, said that he was a student at Stanford when he first encountered Professor Girard’s work, and that it later inspired him to quit an unfulfilling law career in New York and go to Silicon Valley.