“It seems profoundly damaging to the dignity of the human being, and for this reason morally illicit, to support a prevention of AIDS that is based on a recourse to means and remedies that violate an authentically human sense of sexuality, and which are a palliative to the deeper suffering which involve the responsibility of individuals and of society.” (John Paul II, November 15, 1989 – addressing the 4th International Conference of the Pontifical Council for the Pastoral Care of Health Care Workers).

1. WORLD AIDS DAY

The United Nations’ (UN) World AIDS Day is held on December 1 each year to honor the victims of the AIDS pandemic and focus attention on the prevention and treatment of HIV and AIDS related conditions. The Catholic Church is often depicted as an obstacle in the struggle against this terrifying disease. In reality, however, the Church’s assessment of the pandemic makes more sense than we might expect. The Christian season of Advent seems a suitable time to reflect on these issues a little more, especially one week after World Aids Day. Those familiar with mimetic theory will once again notice how the insights of René Girard shine through, and how MT once again proves to be a poignant framework for analysing our ongoing ‘human affairs’.

2. MORE COMPLEX SOCIAL TRUTHS COVERED UP BY MEDIATIZED SCAPEGOAT MECHANISMS

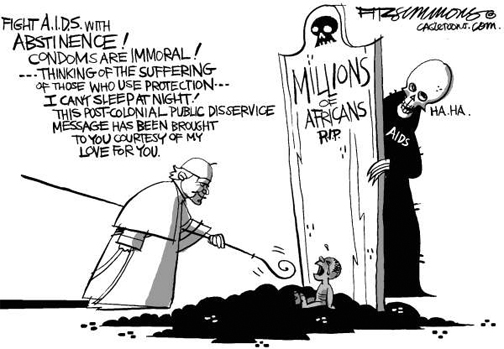

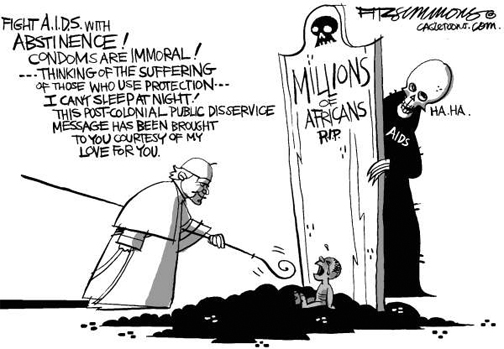

Edward C. Green (senior research scientist at the Harvard School of Public Health) and Michael Cook (editor of BioEdge and MercatorNet) both wrote interesting articles on the massive problem of HIV and AIDS in Africa, questioning the assumption of some media that the Catholic Church and John Paul II in particular are responsible for millions of African AIDS victims. Cook’s article is aptly entitled In search of a scapegoat. He asks whether John Paul II was indeed the greatest mass murderer of the 20th century. To answer this question, he presents some data which ought to make us westerners reflect on the way we usually construct our perception of different African problems.

Recent empirical evidence seems to support the Church’s claim that the problem of AIDS in Africa won’t be solved by a one-sided promotion of condom-use. Edward C. Green’s contribution in the Washington Post (March 29, 2009), Condoms, HIV-AIDS and Africa – The Pope Was Right, points to a very paternalistic, even patronizing tendency in the way we present solutions to the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Africa. We all too often seem to project the social context wherein we make use of condoms, onto radically different African situations. In the words of Green: “The condom has become a symbol of freedom and – along with contraception – female emancipation, so those who question condom orthodoxy are accused of being against these causes.” The reality, of course, is that the use of condoms in Africa – and the Third World in general – is often promoted to protect more or less suppressed young women and sex workers against imprudent and excessive sexual demands. This reality itself often remains ‘untouched’ by the promotion of condom-use. Green again, from the same article: “… liberals and conservatives agree that condoms cannot address challenges that remain critical in Africa such as cross-generational sex, gender inequality and an end to domestic violence, rape and sexual coercion.”

So, instead of becoming a symbol of emancipation and freedom, the condom in the Third World seems well on its way to transform into a fig leaf behind which systems of social inequality are hidden. In some instances, the success of condom-use suggests a relapse in the urgency to fundamentally tackle social issues. The promotion of condom-use to fight the HIV/AIDS epidemic did work in some Asian countries. However, perhaps not surprisingly, this happened in the context of an exploitative sex-industry, which is supported in large by western sex tourists and (therefore?) remains insufficiently criticized. Green, once more: “Let me quickly add that condom promotion has worked in countries such as Thailand and Cambodia, where most HIV is transmitted through commercial sex and where it has been possible to enforce a 100 percent condom use policy in brothels (but not outside of them).”

So, instead of becoming a symbol of emancipation and freedom, the condom in the Third World seems well on its way to transform into a fig leaf behind which systems of social inequality are hidden. In some instances, the success of condom-use suggests a relapse in the urgency to fundamentally tackle social issues. The promotion of condom-use to fight the HIV/AIDS epidemic did work in some Asian countries. However, perhaps not surprisingly, this happened in the context of an exploitative sex-industry, which is supported in large by western sex tourists and (therefore?) remains insufficiently criticized. Green, once more: “Let me quickly add that condom promotion has worked in countries such as Thailand and Cambodia, where most HIV is transmitted through commercial sex and where it has been possible to enforce a 100 percent condom use policy in brothels (but not outside of them).”

Should this kind of ‘success’ become the example of how to fight the spread of HIV/AIDS in Africa? Apart from revealing some sort of perverse cynicism towards the abilities of developing countries to really take matters into their own hands and change the ways of their ‘corrupted worlds’ (and the West’s share in that corruption), this idea of ‘choosing the lesser evil’ is doomed to fail in African countries, as is shown by recent history. Edward C. Green points out two important reasons for this failure: “One reason is ‘risk compensation.’ That is, when people think they’re made safe by using condoms at least some of the time, they actually engage in riskier sex. Another factor is that people seldom use condoms in steady relationships because doing so would imply a lack of trust. (And if condom use rates go up, it’s possible we are seeing an increase of casual or commercial sex.) However, it’s those ongoing relationships that drive Africa’s worst epidemics. In these, most HIV infections are found in general populations, not in high-risk groups such as sex workers, gay men or persons who inject drugs. And in significant proportions of African populations, people have two or more regular sex partners who overlap in time. In Botswana, which has one of the world’s highest HIV rates, 43 percent of men and 17 percent of women surveyed had two or more regular sex partners in the previous year. These ongoing multiple concurrent sex partnerships resemble a giant, invisible web of relationships through which HIV/AIDS spreads. A study in Malawi showed that even though the average number of sexual partners was only slightly over two, fully two-thirds of this population was interconnected through such networks of overlapping, ongoing relationships.”

To put it more bluntly, in developing countries condoms seem consistently used by professional (often exploited) sex workers, but fail to have any lasting impact on people’s promiscuous behavior outside the context of commercial sex. It is noteworthy that in both instances the use of condoms doesn’t affect the way in which people, especially women, are treated. Michael Cook remains ‘grounded’ as he refers to the seemingly far more fundamental social causes of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Africa: “The… assumption is that condoms are essential for preventing AIDS in Africa. In the words of researchers at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, ‘The condom is a life-saving device: it is highly effective in preventing HIV transmission if used correctly and consistently, and is the best current method of HIV prevention for those who are sexually active and at risk’. However, notice that this dogma is limited by two significant qualifications: ‘if used correctly and consistently’. How often can we expect this to happen in southern Africa? If the experts haven’t been able to end AIDS in San Francisco and Sydney by promoting condoms, what makes them think that they will succeed in Africa? […] In the chaotic social environment of many African countries, where poverty is endemic, women are regularly abused and polygamy is widespread, men are unlikely to use condoms consistently. As President Museveni of Uganda has observed, ‘In countries like ours, where a mother often has to walk 20 miles to get an aspirin for her sick child or five miles to get any water at all, the question of getting a constant supply of condoms may never be resolved’. A recent study of condom use in the developing world in the journal Studies in Family Planning summed up the situation with these damning words: ‘no clear examples have emerged yet of a country that has turned back a generalised epidemic primarily by means of condom promotion’. This is most clearly seen in southern Africa. High HIV transmission rates have continued despite high rates of condom use. In Botswana, says Professor Norman Hearst, of the University of California at San Francisco, condom sales rose from one million in 1993 to 3 million in 2001 while HIV prevalence amongst urban pregnant women rose from 27 per cent to 45 percent. In Cameroon condom sales rose from 6 million to 15 million while HIV prevalence rose from 3 per cent to 9 per cent.”

3. THE POPE WAS/IS RIGHT?

The Church, and John Paul II in particular, has always – consistently and stubbornly – focused on the social realities behind the problem of HIV/AIDS in Africa. That’s why, besides also sometimes distributing condoms as a ‘last resort’, Catholic field workers keep on engaging in educational programs to empower women and to humanize sexual relationships. Michael Cook: “About 27 per cent of health care for HIV/AIDS victims is provided by Church organisations and Catholic NGOs… They form a vast network of clinics which reach the poorest, most remote and most neglected people in Africa.” More and more, and contrary to popular opinion in the so-called First World, the assumptions and strategies of these Church organizations are – though somewhat stealthily – adopted by experts, especially following some recent studies concerning the effectiveness of condom-use promotion. Edward C. Green: “In 2003, Norman Hearst and Sanny Chen of the University of California conducted a condom effectiveness study for the United Nations’ AIDS program and found no evidence of condoms working as a primary HIV-prevention measure in Africa. UNAIDS quietly disowned the study. (The authors eventually managed to publish their findings in the quarterly Studies in Family Planning.) Since then, major articles in other peer-reviewed journals such as the Lancet, Science and BMJ have confirmed that condoms have not worked as a primary intervention in the population-wide epidemics of Africa. In a 2008 article in Science called ‘Reassessing HIV Prevention’ 10 AIDS experts concluded that ‘consistent condom use has not reached a sufficiently high level, even after many years of widespread and often aggressive promotion, to produce a measurable slowing of new infections in the generalized epidemics of Sub-Saharan Africa.'”

We should carefully pay attention to what’s actually being said here. Condom-use is not condemned, it’s just presented – in accordance to ‘the facts on the ground’ – as not being the real and morally desirable solution to the problem of HIV/AIDS in Africa. At the end of his article, Green once again stresses what experts nowadays perceive as ‘the first priority’ to assess the epidemic – and indeed seems to show that ‘The Pope Was Right’: “Don’t misunderstand me; I am not anti-condom. All people should have full access to condoms, and condoms should always be a backup strategy for those who will not or cannot remain in a mutually faithful relationship. This was a key point in a 2004 ‘consensus statement’ published and endorsed by some 150 global AIDS experts, including representatives of the United Nations, World Health Organization and World Bank. These experts also affirmed that for sexually active adults, the first priority should be to promote mutual fidelity.”

In a 2010 interview with German journalist Peter Seewald, pope Benedict XVI responded to the statement that “It is madness to forbid a high-risk population to use condoms” by the following reflection (which is very much in line with the recent conclusions of experts in the field): “There may be a basis in the case of some individuals, as perhaps when a male prostitute uses a condom, where this can be a first step in the direction of a moralization, a first assumption of responsibility, on the way toward recovering an awareness that not everything is allowed and that one cannot do whatever one wants. But it is not really the way to deal with the evil of HIV infection. That can really lie only in a humanization of sexuality. [The Church] of course does not regard [the use of condoms] as a real or moral solution, but, in this or that case, there can be nonetheless, in the intention of reducing the risk of infection, a first step in a movement toward a different way, a more human way, of living sexuality.”

population to use condoms” by the following reflection (which is very much in line with the recent conclusions of experts in the field): “There may be a basis in the case of some individuals, as perhaps when a male prostitute uses a condom, where this can be a first step in the direction of a moralization, a first assumption of responsibility, on the way toward recovering an awareness that not everything is allowed and that one cannot do whatever one wants. But it is not really the way to deal with the evil of HIV infection. That can really lie only in a humanization of sexuality. [The Church] of course does not regard [the use of condoms] as a real or moral solution, but, in this or that case, there can be nonetheless, in the intention of reducing the risk of infection, a first step in a movement toward a different way, a more human way, of living sexuality.”

The promotion of relationships based on mutual respect and, if possible, mutual fidelity, indeed has proven to be more effective than a one-sided promotion of condoms without addressing social issues. This is shown by the example of Uganda. Edward C. Green: “So what has worked in Africa? Strategies that break up… multiple and concurrent sexual networks – or, in plain language, faithful mutual monogamy or at least reduction in numbers of partners, especially concurrent ones. ‘Closed’ or faithful polygamy can work as well. In Uganda’s early, largely home-grown AIDS program, which began in 1986, the focus was on ‘Sticking to One Partner’ or ‘Zero Grazing’ (which meant remaining faithful within a polygamous marriage) and ‘Loving Faithfully.’ These simple messages worked. More recently, the two countries with the highest HIV infection rates, Swaziland and Botswana, have both launched campaigns that discourage people from having multiple and concurrent sexual partners.” Michael Cook, on the same example of Uganda, which deserves to be imitated and improved upon: “In fact, the history of AIDS in Uganda supports the Church’s belief that abstinence and fidelity within marriage are actually the best ways to fight AIDS. In 1991, the infection rate in Uganda was 21 per cent. Now, after years of a simple, low-cost program called ABC, it has dropped to about 6 per cent. ABC stands for Abstain, Be faithful, or use Condoms if A and B are not practiced. Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni preaches the ABC of AIDS with the fervour of an evangelist. ‘I am not in favour of condoms in primary and even secondary schools… Let condoms be a last resort,’ he said recently at an international AIDS conference in his capital, Kampala. ‘I have grown-up children and my policy was to frighten them out of undisciplined sex. I started talking to them from the age of 13, telling them to concentrate on their studies, that the time would come for sex’. Ms Toynbee contended in [a] diatribe in the Guardian that ‘abstinence and celibacy are not the human condition’. But Museveni – no innocent about the human condition – thinks that they are. ‘We made it our highest priority to convince our people to return to their traditional values of chastity and faithfulness or, failing that, to use condoms,’ he told American pharmaceutical executives a couple of years ago. ‘The alternative was decimation’.”

4. MASS MEDIA: THE HOWLING CROWD

Considering all these facts, I cannot escape the impression that the outrage of our western mass media over the millions of AIDS victims in Africa, is often but a pretext to scorn the Catholic Church. It has become one more outlet for the hollow and howling crowds of ‘Pharisees’ in the West who vainly try to boast of some moral superiority. In other words, some media exploit the way in which the Church addresses the HIV/AIDS epidemic (especially in Africa) to serve their own ends, adding absolutely nothing to the solution of this scourge (as John Paul II called it). Moreover, these media actually keep on perceiving African people in a patronizing way. Africans are – at least implicitly – said to be incapable of educating themselves and to be highly dependent of our western ways of life as models we present them to live by. In a sense, popular opinion in the West concerning Africa only mimics a spirit of earlier ‘Catholic’ colonialism it desperately seeks to differ itself from.

We often fail to raise the question whether our ways of life are actually worth imitating, and at the same time we exaggerate our (and, for that matter, the pope’s) influence on the minds and the behavior of ‘the African people’. Michael Cook reveals the underlying paternalism, simplistic reasoning and contradictions in the way some of our media abuse the spread of HIV/AIDS in Africa to demonize the late John Paul II and the Catholic Church in general: “… there is something absurdly medieval about making the Pope a scapegoat, as if the clouds would break and the sun shine if we thrust enough pins through a JP2 voodoo doll. Pinning the blame for the tragedy of African AIDS on one man is one of those ideas that are, in the words of George Orwell, ‘so stupid that only intellectuals could believe them.’ Two such ideas run  through all these criticisms. The first is basically this: African Catholics are so devout that if they have sex outside of marriage, dally with prostitutes or take a third wife, they will piously refrain from using condoms because the Great White Father told them not to. Ms Toynbee [in an already mentioned article in the Guardian] darkly invokes ‘the Vatican’s deeper power… its personal authority over 1.3 billion worshippers, which is strongest over the poorest, most helpless devotees.’ But she can’t have it both ways: these benighted dark-skinned Catholics can’t be both too goody-two-shoes to use condoms and too wicked to resist temptation. Journalist Brendan O’Neill – who describes himself as an ex-Catholic who has jettisoned Catholic teaching on sexual morality – sums up this patronising argument in the on-line journal Spiked: ‘The only reason you could believe the fantastically simplistic idea that Vatican edict = AIDS in Africa is if you consider Africans to be little more than automatons… who do as they are told’. Superimposing maps of prevalence of AIDS on prevalence of Catholicism is enough to sink the link between the Catholic Church and AIDS. In the hospice which is Swaziland nowadays, only about 5 per cent of the population is Catholic. In Botswana, where 37 per cent of the adult population is HIV infected, only 4 per cent of the population is Catholic. In South Africa, 22 per cent of the population is HIV infected, and only 6 per cent is Catholic. But in Uganda, with 43 per cent of the population Catholic, the proportion of HIV infected adults is 4 per cent.”

through all these criticisms. The first is basically this: African Catholics are so devout that if they have sex outside of marriage, dally with prostitutes or take a third wife, they will piously refrain from using condoms because the Great White Father told them not to. Ms Toynbee [in an already mentioned article in the Guardian] darkly invokes ‘the Vatican’s deeper power… its personal authority over 1.3 billion worshippers, which is strongest over the poorest, most helpless devotees.’ But she can’t have it both ways: these benighted dark-skinned Catholics can’t be both too goody-two-shoes to use condoms and too wicked to resist temptation. Journalist Brendan O’Neill – who describes himself as an ex-Catholic who has jettisoned Catholic teaching on sexual morality – sums up this patronising argument in the on-line journal Spiked: ‘The only reason you could believe the fantastically simplistic idea that Vatican edict = AIDS in Africa is if you consider Africans to be little more than automatons… who do as they are told’. Superimposing maps of prevalence of AIDS on prevalence of Catholicism is enough to sink the link between the Catholic Church and AIDS. In the hospice which is Swaziland nowadays, only about 5 per cent of the population is Catholic. In Botswana, where 37 per cent of the adult population is HIV infected, only 4 per cent of the population is Catholic. In South Africa, 22 per cent of the population is HIV infected, and only 6 per cent is Catholic. But in Uganda, with 43 per cent of the population Catholic, the proportion of HIV infected adults is 4 per cent.”

5. FOR UNTO US A CHILD IS BORN…

We should learn from what happens in Uganda. We should be aware of the precarious and fragile situation countries like these find themselves in. But we should also be aware of the living hope in the hearts of their inhabitants. What message are we directing to the world if we convince ourselves that we ‘should be realistic’, and that the promotion of condom-use is often but the only thing we can do to ‘educate’ the ‘socially deprived’? Are we, once again, promoting our own ‘freedom’ at the cost of impoverished sex workers – victims we can exploit to answer the demands for a despicable kind of ‘tourism’? Who are we to impose our (self-)destructive ways?

We should learn from what happens in Uganda. We should be aware of the precarious and fragile situation countries like these find themselves in. But we should also be aware of the living hope in the hearts of their inhabitants. What message are we directing to the world if we convince ourselves that we ‘should be realistic’, and that the promotion of condom-use is often but the only thing we can do to ‘educate’ the ‘socially deprived’? Are we, once again, promoting our own ‘freedom’ at the cost of impoverished sex workers – victims we can exploit to answer the demands for a despicable kind of ‘tourism’? Who are we to impose our (self-)destructive ways?

What message are we directing to the world if we convince ourselves – looking at the misery of millions around the globe from our cosy and luxurious homes – that ‘there are lots of worse things than never being born’? Are we actually implying that we ‘need’ the suffering of the world to make death a hero?! A world wherein death is welcomed as a ‘hero’ is a morally perverse world. Throughout history human beings have found the strength to transform the struggle for survival into a token of life and dignity, refusing to slavishly undergo the whims of fate. The Hebrew Bible is one of those testimonies of hope against despair, of dignity in the midst of suffering, of life against death, written by a people of ‘losers’ or ‘victims’. Maybe its message will never be fully understood by the so-called influential and powerful – they might abuse it to suppress others even more – , while it is being lived by the so-called fragile and powerless people…

The ‘First World’ is experiencing a deep crisis, hiding its spiritual wasteland behind an unavoidable economic depression of a materialist, empty and self-consuming culture of death. It’s in this world, our world, that the AIDS orphan is born. This child seems to have ‘no home’, but his coming is the real, often uninvited and unaccepted ‘Advent’ and Promise of Life, despite everything. For God’s sake, who could not notice his splendor, glory and might? His birth is a reminder that our world can be healed, as he blesses our sick cynicism before we even realize we threaten to contaminate the physically sick and dying with our messages of desperation. For, unto us a Child is born… and maybe, in order to receive Him properly, we should alter ‘the world we created…’