We all know the story:

- The Christian faith is, by its very nature, an enemy of science.

- The Catholic Church has, during its history, vehemently and violently suppressed scientists who came up with new scientific ideas.

- Scientists from the past who believed in God did so because of their upbringing, or they faked it because they feared prosecution by religious authorities.

- For proof of all of the above, one just has to look at what happened to Galileo Galilei or Giordano Bruno.

- Historians who criticize these views are biased Catholic apologists.

Today we should know that this story is itself biased and apologetic of the view that the Catholic Church (or even religion in general) is one of the main sources of superstitious darkness and evil in the world. One of the books that dismantles the myth of the Catholic Church as sworn enemy to science, is Galileo Goes to Jail and Other Myths about Science and Religion (pdf). It was edited by Prof. Ronald L. Numbers and published by Harvard University Press in 2009. The word myth in the title means what it means in everyday conversation and thus refers to a claim that is false.

Today we should know that this story is itself biased and apologetic of the view that the Catholic Church (or even religion in general) is one of the main sources of superstitious darkness and evil in the world. One of the books that dismantles the myth of the Catholic Church as sworn enemy to science, is Galileo Goes to Jail and Other Myths about Science and Religion (pdf). It was edited by Prof. Ronald L. Numbers and published by Harvard University Press in 2009. The word myth in the title means what it means in everyday conversation and thus refers to a claim that is false.

In his introduction, Numbers briefly mentions the ideological background of the 25 authors who each debunk a myth on the relation between science and religion. Perhaps because he is aware that some people don’t necessarily have a scientific mindset (although they might claim the opposite). A scientist normally reads what is written, critically weighing the rational and scientific arguments that are brought up. If someone asks who wrote something to judge whether a text is truthful, he or she is not really judging from scientific criteria. Anti-theists (from the so-called “new atheist” corner) often think that the religious views of an author automatically get in the way of scientific research, and then close themselves off from further reading. This close-mindedness is, of course, not a sole preserve of new atheists. Theists also might not be free enough to hear what atheists have to say, thinking that atheists are automatically anti-theists, who push an often emotionally driven campaign against religion. Seemingly to reassure the lesser scientific minds on both sides, Numbers gives his overview: nearly half of the book’s contributors (twelve out of twenty-five) are unbelievers (agnostic or atheist), five are mainstream Protestants, two are evangelical Protestants, one is a Roman Catholic, one a Jew, another a Muslim, one a Buddhist, and the beliefs of yet two others fit no conventional category. This already makes clear that not everyone who criticizes the above mentioned myth is a biased Catholic, since there is only one Roman Catholic among the 25 authors of Galileo Goes to Jail.

Among many other interesting facts, the book provides and proves some important points regarding the Galileo Galilei and Giordano Bruno case. Both Galileo and Bruno defended heliocentrism, a view that was at the time developed most prominently by Nicolaus Copernicus. Both men received their education within the Catholic Church. However, while Galileo remained a genuinely pious Roman Catholic (a fact that is overlooked sometimes), Bruno converted to the so-called Hermetic Tradition (Hermeticism). The reason why Bruno was an adherent of heliocentrism, was because of his religious views (and not because of a scientific insight independent of religion!). As is also the case for his contemporary scientific colleagues, Bruno did not separate matters of science (“natural philosophy” at the time) from religious matters. (Natural) philosophy and theology were, eventually, one and the same. From Galileo Goes to Jail, pp 66-67:

In Bruno’s day, indeed in his own writings, theology and philosophy were of one piece, inseparable. He stated this succinctly in the prefatory letter dedicating The Cabala of Pegasus (1585) to the fictional Bishop of Casamarciano: “I don’t know if you are a theologian, philosopher, or cabalist – but I know for sure that you are all of these… And therefore, here you have it – cabala, theology and philosophy; I mean, a cabala of theological philosophy, a philosophy of kabbalistic theology, a theology of philosophical cabala.” Clearly Bruno thought of his work as all three and incomplete if construed as any one of them alone; he wrote as a philosopher but reckoned himself a Professor of Sacred Theology.

Also, Ibid., p 98:

Seventeenth-century natural philosophers were not modern scientists. Their exploration of the natural world was not cut off from their religious views and theological assumptions. That separation came later. Reading the past from the standpoint of later developments has led to serious misunderstandings of the Scientific Revolution. For many of the natural philosophers of the seventeenth century, science and religion – or, better, natural philosophy and theology – were inseparable, part and parcel of the endeavor to understand our world.

Giordano Bruno was eventually burned at the stake in 1600. Although this is of course an appalling punishment, Bruno was not burned because of an anachronistic modern scientific worldview, but because of a number of so-called religious heresies (which he didn’t fake, by the way; apparently he was even prepared to die for them). His “Pythagorean” convictions (the way the heliocentric hypothesis was sometimes referred to at the time) included, for instance, the belief in the transmigration of souls. As is known, the Catholic Church had just gone through a period of a stricter attention to orthodoxy, because of the turmoil created by the Reformation and Counter-reformation. Therefore the Church, as all human endeavors tend to do in circumstances questioning the cornerstones of their sense of identity, could barely stand what it experienced as new attacks on its identity. It may remind some people of the difficulty certain anti-theists experience to accept criticism on their views about religion. Of course anti-theists don’t burn people at the stake, unless, of course, their hatred of religion comes from some “neo-Stalinist” worldview. In that case, theists should run for their lives.

Giordano Bruno was eventually burned at the stake in 1600. Although this is of course an appalling punishment, Bruno was not burned because of an anachronistic modern scientific worldview, but because of a number of so-called religious heresies (which he didn’t fake, by the way; apparently he was even prepared to die for them). His “Pythagorean” convictions (the way the heliocentric hypothesis was sometimes referred to at the time) included, for instance, the belief in the transmigration of souls. As is known, the Catholic Church had just gone through a period of a stricter attention to orthodoxy, because of the turmoil created by the Reformation and Counter-reformation. Therefore the Church, as all human endeavors tend to do in circumstances questioning the cornerstones of their sense of identity, could barely stand what it experienced as new attacks on its identity. It may remind some people of the difficulty certain anti-theists experience to accept criticism on their views about religion. Of course anti-theists don’t burn people at the stake, unless, of course, their hatred of religion comes from some “neo-Stalinist” worldview. In that case, theists should run for their lives.

All these matters aside, in fact, essentially the debate between Catholics (and others) who were defending the heliocentric hypothesis and Catholics (and others) who weren’t, was a debate between ancient Greek philosophers with slightly different religious convictions. For centuries, the worldview of Aristotle and Ptolemy had dominated intellectual life, as it was adopted by Christian theology. People like Copernicus, Galileo and Kepler challenged this view, at the same time challenging mainstream medieval theology. From Galileo Goes to Jail, p 83:

In the sixteenth century, Nicolaus Copernicus’s (1473–1543) view that the sun is at the center of the universe was often called the “Pythagorean hypothesis,” and Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) and Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) both traced the roots of their innovations back to Plato. These men and their contemporaries all knew what some today have forgotten, that Christian astronomers (and other students of nature) owe a great debt to their Greek forebears.

Observations like these already debunk another myth, namely that Christianity gave birth to modern science. Although the Catholic Church played a significant role (see below) in the birth and development of modern science, it was self-evidently not the sole factor. Again, from Galileo Goes to Jail, p 83:

Christian astronomers (and other students of nature) owe a great debt to their Greek forebears. This was not the only debt outstanding for Christian philosophers of nature. They had also benefited directly and indirectly from Muslim and, to a lesser degree, Jewish philosophers of nature who used Arabic to describe their investigations. It was in Muslim lands that natural philosophy received the most careful and creative attention from the seventh to the twelfth century.

Nevertheless, the discussion about heliocentrism at the dawn of the modern era was also (and perhaps mainly) a discussion within the Church, among Catholics (intellectuals engaged in matters of natural philosophy)! A more extended quote from Galileo Goes to Jail, pp 101-106:

It would of course be absurd to claim that there have been no instances of Catholic laymen or clerics opposing scientific work in some form or other. Without question, such examples can be found, and quite easily. Yet it would be equally absurd to extend these examples of opposition – no matter how ignorant or illconceived – to the Catholic church or to Catholics as a whole. This act would be to commit the historical sin of overgeneralization, that is, the unwarrantable extension of the actions or thought of one member of a collective body to the entire body as a whole. (For example, there are apparently American flatearthers alive today, yet it is not correct then to say that twentyfirst-century Americans in general believe that the earth is flat.)

The Catholic church is not, and has never been (perhaps to the chagrin of some pontiffs), a monolithic or unanimous entity; it is composed of individuals and groups who often hold widely divergent viewpoints. This diversity of opinion was in full evidence even in the celebrated case of Galileo, where clerics and laymen are to be found distributed across the whole spectrum of responses from support to condemnation. The question, then, is what the preponderant attitude was, and in this case it is clear from the historical record that the Catholic church has been probably the largest single and longest-term patron of science in history, that many contributors to the Scientific Revolution were themselves Catholic, and that several Catholic institutions and perspectives were key influences upon the rise of modern science.

In contrast to our starting myth, it is an easy matter to point to important figures of the Scientific Revolution who were themselves Catholics. The man often credited with the first major step of the Scientific Revolution, Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543), was not only Catholic but in Holy Orders as a cathedral canon (a cleric charged with administrative duties). And lest it be said that he was simultaneously persecuted for his astronomical work, it must be pointed out that much of his audience and support came from within the Catholic hierarchy, and especially the Papal Court. His book begins with a dedication to Pope Paul III that contains an account of the various church officials who supported his work and urged its completion and publication. Galileo, too, despite his celebrated and much mythologized face-off with church officials, was and remained Catholic, and there is no reason to question the sincerity of his faith.

A catalog of Catholic contributors to the Scientific Revolution would run to many pages and exhaust the reader’s patience. Thus it will suffice to mention just a very few other representatives from various scientific disciplines. In the medical sciences, there is Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564), the famous anatomist of Brussels; while another Fleming, Joan Baptista Van Helmont (1579–1644), one of the most innovative and influential voices in seventeenth-century medicine and chemistry, was a devout Catholic with strong mystical leanings. In Italy, the microscopist Marcello Malpighi (1628–1694) first observed capillaries, thus proving the circulation of the blood. Niels Stensen (or Nicolaus Steno, 1638–1686), who remains known today for his foundational work on fossils and the geological formation of rock strata, converted to Catholicism during his scientific work and became first a priest, then a bishop, and is currently a beatus (a title preliminary to official sainthood). [Another famous convert to Christianity from the same period is the brilliant French mathematician and physicist Blaise Pascal]. The revival and adaptation of ancient atomic ideas was due in no small part to the work of the Catholic priest Pierre Gassendi (1592–1655). The Minim friar Marin Mersenne (1588–1648), besides his own competence in mathematics, orchestrated a network of correspondence to disseminate scientific and mathematical discoveries, perhaps most notably the ideas of René Descartes (1596–1650), another Catholic.

Besides individuals there are also institutions to be mentioned. The first scientific societies were organized in Italy and were financed and populated by Catholics. The earliest of these, the Accademia dei Lincei, was founded in Rome in 1603. Many other societies followed across Italy, including the Accademia del Cimento, founded in Florence in 1657, that brought together many experimentalists and former students of Galileo. Later, the Royal Academy of Sciences in Paris, founded in 1666 and probably the most stable and productive of all early scientific societies, had a majority of Catholic members, such as Gian Domenico Cassini (1625–1712), famed for his observations of Jupiter and Saturn, and Wilhelm Homberg (1653–1715), a convert to Catholicism and one of the most renowned and productive chemists of his day. Four of the early members were in orders, including the abbe Jean Picard (1620–1682), a noted astronomer, and the abbe Edme Mariotte (ca. 1620–1684), an important physicist. Even the Royal Society of London, founded in very Protestant England in 1660, had a few Catholic members, such as Sir Kenelm Digby (1603–1665), and kept up a vigorous correspondence with Catholic natural philosophers in Italy, France, and elsewhere.

Catholic religious orders provided a variety of opportunities for natural-philosophical work. One of Galileo’s closest early students and supporters, and his successor to the chair of mathematics at the University of Pisa, was the Benedictine monk Benedetto Castelli (1578–1643). But on a broader scale, during the Scientific Revolution, Catholic monks, friars, and priests in missions constituted a virtual worldwide web of correspondents and data collectors. Information on local geography, flora, fauna, mineralogy, and other subjects as well as a wealth of astronomical, meteorological, and seismological observations flooded back into Europe from far-flung Catholic missions in the Americas, Africa, and Asia. The data and specimens they sent back were channeled into natural-philosophical treatises and studies by Catholics and Protestants alike. This massive collection of new scientific information was carried out by Franciscans, Dominicans, Benedictines, and, perhaps most of all, Jesuits.

No account of Catholic involvement with science could be complete without mention of the Jesuits (officially called the Society of Jesus). Formally established in 1540, the society placed such special emphasis on education that by 1625 they had founded nearly 450 colleges in Europe and elsewhere. Many Jesuit priests were deeply involved in scientific issues, and many made important contributions. The reformed calendar, enacted under Pope Gregory XIII in 1582 and still in use today, was worked out by the Jesuit mathematician and astronomer Christoph Clavius (1538–1612). Optics and astronomy were topics of special interest for Jesuits. Christoph Scheiner (1573–1650) studied sunspots, Orazio Grassi (1583–1654) comets, and Giambattista Riccioli (1598–1671) provided a star catalog, a detailed lunar map that provided the names still used today for many of its features, and experimentally confirmed Galileo’s laws of falling bodies by measuring their exact rates of acceleration during descent. Jesuit investigators of optics and light include Francesco Maria Grimaldi (1618–1663), who, among other things (such as collaborating with Riccioli on the lunar map), discovered the phenomenon of the diffraction of light and named it. Magnetism as well was studied by several Jesuits, and it was Niccolo Cabeo (1586–1650) who devised the technique of visualizing the magnetic field lines by sprinkling iron filings on a sheet of paper laid on top of a magnet. By 1700, Jesuits held a majority of the chairs of mathematics in European universities.

Undergirding such scientific activities in the early-modern period was the firm conviction that the study of nature is itself an inherently religious activity. The secrets of nature are the secrets of God. By coming to know the natural world we should, if we observe and understand rightly, come to a better understanding of their Creator. This attitude was by no means unique to Catholics, but many of the priests and other religious involved in teaching and studying natural philosophy underscored this connection. For example, the Jesuit polymath Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680) envisioned the study of magnetism not only as teaching about an invisible physical force of nature but also as providing a powerful emblem of the divine love of God that holds all creation together and draws the faithful inexorably to Him. Indeed, if Jesuit work remains today inadequately represented in accounts of scientific discovery, it is in part because science proceeded down a path of literalism and dissection rather than following the Jesuits’ path of comprehensive and emblematic holism.

Finally, historians of science now recognize that the impressive developments of the period called the Scientific Revolution depended in large part on positive contributions and foundations dating from the High Middle Ages, that is to say, before the origins of Protestantism. This fact too must be brought to bear on the role of Catholics and their church in the Scientific Revolution. Medieval observations and theories of optics, kinematics, astronomy, matter, and other fields provided essential information and starting points for developments of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The medieval establishment of universities, the development of a culture of disputation, and the logical rigor of Scholastic theology all helped to provide a climate and culture necessary for the Scientific Revolution.

Neither interest and activity in science nor criticism and suppression of its tenets align with the confessional boundary between Catholics and Protestants. Modern science is not a product of Protestantism and certainly not of atheism or agnosticism. Catholics and Protestants alike made essential and fundamental contributions to the developments of the period we have called the Scientific Revolution.

Indeed, as the above quoted text mentions, within the Catholic Church the order of the Jesuits holds a special place regarding the origins and further development of modern science. As the astronomer George Coyne points out, himself a Jesuit priest, Galileo’s observations caused tensions within the Jesuit order at the time, and eventually Jesuits at the Roman College confirmed the earth-shaking ideas of their fellow Catholic. It is truly worth reading Coyne’s paper on the relationship between Galileo and his Jesuit colleagues, The Jesuits and Galileo: Fidelity to Tradition and the Adventure of Discovery (pdf).

Some people, especially so-called anti-theistic new atheists, claim that all those great Catholic or other Christian scientists and mathematicians from the past believed in God simply because they were raised that way, or because they feared prosecution. Maybe some anti-theists have special powers, able to read the minds of people who died a long time back. In any case, what those scientists wrote about their own faith suggests otherwise. Some got in conflict with religious authorities, claiming that those authorities betrayed the Christian faith. Alright, maybe they all participated in a conspiracy to raise the impression that they had a strong spiritual mind, thinking profoundly, honestly and individually about the Christian tradition. However, so long as we don’t have any proof of such a conspiracy, and as long as we don’t have any proof of anti-theistic paranormal powers, we should perhaps abandon the paternalistic claim that those great, innovative minds were not able to think about their faith in a mature way. Once again, from Galileo Goes to Jail, p 81:

René Descartes (1596–1650) boasted of his physics that “my new philosophy is in much better agreement with all the truths of faith than that of Aristotle.” Isaac Newton (1642–1727) believed that his system restored the original divine wisdom God had provided to Moses and had no doubt that his Christianity bolstered his physics – and that his physics bolstered his Christianity.

Or take Galileo, Ibid., p 96:

Another theme common to early-modern discussions about the possibility of human knowledge of the creation was that expressed by the metaphor of God’s two books: the book of God’s word (the Bible) and the book of God’s work (the created world). Natural philosophers regarded both books as legitimate sources of knowledge. Early in the seventeenth century, Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) appealed to this metaphor in the context of a discussion of the relative importance of studying the Bible and observing natural phenomena: “the holy Bible and the phenomena of nature proceed alike from the divine Word, the former as the dictate of the Holy Ghost and the latter as the observant executrix of God’s commands.”

As for the further relationship between what became modern science and the Christian Bible, it should be clear how it eventually developed. Georges Lemaître‘s ideas may serve as an example. This Belgian Catholic priest and famous physicist (founder of the “Big Bang” hypothesis among others) clearly distinguishes the questions of modern science from the questions the New Testament authors deal with. In fact, according to Lemaître, questions of modern science have nothing to do with theology, and vice versa. The Christian scientist thus cannot let his faith be of any importance for his scientific work. Some quotes from Lemaître, taken from an article by Joseph R. Laracy (click to read) clarify his position regarding the relationship between theology and modern science:

Should a priest reject relativity because it contains no authoritative exposition on the doctrine of the Trinity? Once you realize that the Bible does not purport to be a textbook of science, the old controversy between religion and science vanishes… The doctrine of the Trinity is much more abstruse than anything in relativity or quantum mechanics; but, being necessary for salvation, the doctrine is stated in the Bible. If the theory of relativity had also been necessary for salvation, it would have been revealed to Saint Paul or to Moses… As a matter of fact neither Saint Paul nor Moses had the slightest idea of relativity.

The Christian researcher has to master and apply with sagacity the technique appropriate to his problem. His investigative means are the same as those of his non-believer colleague… In a sense, the researcher makes an abstraction of his faith in his researches. He does this not because his faith could involve him in difficulties, but because it has directly nothing in common with his scientific activity. After all, a Christian does not act differently from any non-believer as far as walking, or running, or swimming is concerned.

The writers of the Bible were illuminated more or less – some more than others – on the question of salvation. On other questions they were as wise or ignorant as their generation. Hence it is utterly unimportant that errors in historic and scientific fact should be found in the Bible, especially if the errors related to events that were not directly observed by those who wrote about them… The idea that because they were right in their doctrine of immortality and salvation they must also be right on all other subjects, is simply the fallacy of people who have an incomplete understanding of why the Bible was given to us at all.

The question about the meaning of “salvation” in the light of the New Testament indeed is different from, for instance, the question how and why objects fall down. That’s how plain and simple an insight can be in order to stop battling windmills like some heroic but mad and narcissistic Don Quixote.

For more on Lemaître, click the following (pdf): The Faith and Reason of Father Georges Lemaître & Priestly Contributions to Modern Science.

The already mentioned astronomer and Jesuit George Coyne also points to the false conflict between modern science and the Bible, for instance in the “mockumentary” Religulous (click here for more):

The Christian Scriptures were written between about 2,000 years before Christ to about 200 years after Christ. That’s it. Modern science came to be with Galileo up through Newton, up through Einstein. What we know as modern science, okay, is in that period. How in the world could there be any science in Scripture? There cannot be. Just the two historical periods are separated by so much. The Scriptures are not teaching science. It’s very hard for me to accept, not just a literal interpretation of scripture, but a fundamentalist approach to religious belief. It’s kind of a plague. It presents itself as science and it’s not.

Not insignificant note: the Roman Catholic Church accepts all kinds of interpretive approaches to the Bible, but it decisively rejects one approach, namely a fundamentalist reading of the Bible (click here for more).

Maybe Coyne says it more beautifully in this TED-talk (click to watch):

Hopefully, together with both Lemaître and Coyne, and with countless other researchers from different ideological backgrounds, it’s a bit more clear now that the story this post started with is indeed a biased myth, even plain propaganda. In the words of Prof. Ronald L. Numbers, from the introduction to Galileo Goes to Jail, pp 1-6:

The greatest myth in the history of science and religion holds that they have been in a state of constant conflict. No one bears more responsibility for promoting this notion than two nineteenth-century American polemicists: Andrew Dickson White (1832–1918) and John William Draper (1811–1882).

[…]

Historians of science have known for years that White’s and Draper’s accounts are more propaganda than history. Yet the message has rarely escaped the ivory tower. The secular public, if it thinks about such issues at all, knows that organized religion has always opposed scientific progress (witness the attacks on Galileo, Darwin, and Scopes). The religious public knows that science has taken the leading role in corroding faith (through naturalism and antibiblicism). As a first step toward correcting these misperceptions we must dispel the hoary myths that continue to pass as historical truths. No scientist, to our knowledge, ever lost his life because of his scientific views, though, the Italian Inquisition did incinerate the sixteenth-century Copernican Giordano Bruno for his heretical theological notions.

Unlike the master mythmakers White and Draper, the contributors to this volume have no obvious scientific or theological axes to grind.

Perhaps the reason why some atheists stubbornly still swallow and believe the propaganda that began with people like White and Draper, is that they need an outside “enemy” to build their identity. If religion in general, and the Catholic Church in particular, can be depicted as a bulwark of stupidity and evil, some atheists can more easily see themselves as belonging to the intelligent and moral part of humanity. Of course, as we know from the Gospels and other spiritual resources: to see the stupidity and immorality of someone else does not automatically make oneself intelligent and moral. Apparently, creating an “us vs them” to get a sense of superiority is a universally human temptation. The French-American anthropologist and literary critic, René Girard (1923-2015), had a profound insight in this matter and its implications.

The way certain atheists build part of their identity by their emotionally driven aversion to religion, also explains why they consider religion as one of the main sources of violence in the world. A claim that can be highly debated, especially from an atheist point of view! Before being religious or secular (communist or nationalistic or whatever), violence is always human violence. Religious ideas originated in humans, they did not come from divine revelation (at least from an atheist perspective). Thus – this can be reasonably expected, as is also clear from a human history of violence – human characteristics that gave birth to certain religious ideas legitimating violence will continue to generate ideas to legitimate violence, whether of a religious or secular nature. The disappearance of one religious or secular ideology legitimating violence does not take away the universally human characteristics that gave birth to the violence in the first place.

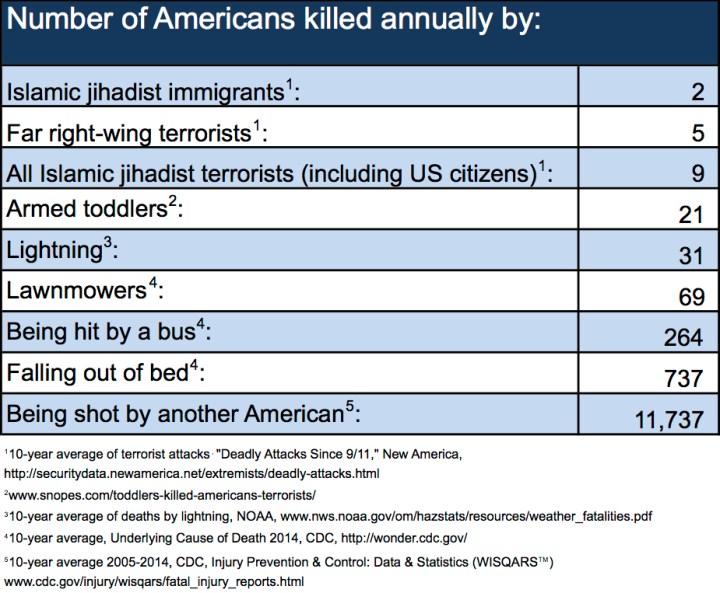

These considerations on the origin of violence might lead to a better assessment of the basic sources of any type of violence. For instance while interpreting recent 10 year average data of annually killed Americans. According to these data, 9 Americans are killed annually by Islamic jihadist terrorists (including jihadists who are US citizens), while 11,737 (almost twelve thousand!) Americans are killed annually by other Americans. Is it really far-fetched to think that those 9 jihadist terrorists would have found other outlets for their psychologically developed frustrations, anger and aggressive tendencies anyway? In the case a violent Islamist ideology was not available? The focus on so-called religious violence (9 killed) gets in the way of attacking the real problem, namely human violence (11,737 + 9).

For instance, the man who killed 84 people in Nice, France, by driving a lorry through a crowd (click here for more), 31 year old Tunisian delivery man Mohamed Lahouaiej-Bouhlel, clearly had identity and social issues. It should be stressed that this “Nice killer” not only searched the web for “jihadist” terror attacks, but that he also looked at shootings like the one in Dallas, where a black army veteran shot five police officers. He was apparently interested in violent acts that would put him in the spotlight and give him a sense of significance, no matter under what flag. The Nice killer thus showed signs of the “copycat effect” (a mimetic phenomenon, indeed): sensational media exposure about violent suicides and murders results in more of the same through imitation. Moreover, this terrorist showed no interest in religion until only a few weeks before his violent act. In short, violent Islamist ideology seemed to be one of the coincidental guises he could use to perform his act. If it were not available, it is very likely that he would have used something else.

Of course it is easy to prove that something is bad or evil. If I would list all the rapes and other acts of sexual violence that happen daily around the world, I could maybe make the claim that “sex is evil”. But that would, luckily, not be the whole story.

In short, if you still believe the story of the Catholic Church as the age-old sworn enemy of science, your historical views belong, metaphorically speaking, to the Middle Ages.

Some content on this page was disabled on August 9, 2019 as a result of a DMCA takedown notice from Harvard University Press. You can learn more about the DMCA here:

The annual and 26th conference of the

The annual and 26th conference of the

at it,

at it,

Well, one thing became clear on the first evening of the conference. The organizers not only provided the participants with a great reception and dinner, they indeed also promised copious food for thought.

Well, one thing became clear on the first evening of the conference. The organizers not only provided the participants with a great reception and dinner, they indeed also promised copious food for thought. From the lectures of Prof. Dupuy and Dr. Bachelard I became more aware of the difference between the terror of today’s violent extremism on the one hand, and the terror of “the fear of MAD (Mutually Assured Destruction)” by a nuclear war during the Cold War on the other. During the Cold War, the threat of total annihilation served as a third party, a non-human entity (an exteriorization of violence) to which both the US and the USSR bowed. A “cold war” thus resulted in a “hot peace” (a nuclear peace). Today’s suicidal terrorists, however, don’t fear annihilation in any way. So the threat of annihilation as a means to establish an ever precarious peace doesn’t work. This means that we are challenged to look for other attempts to create peace which don’t alienate us from “the best of ourselves”.

From the lectures of Prof. Dupuy and Dr. Bachelard I became more aware of the difference between the terror of today’s violent extremism on the one hand, and the terror of “the fear of MAD (Mutually Assured Destruction)” by a nuclear war during the Cold War on the other. During the Cold War, the threat of total annihilation served as a third party, a non-human entity (an exteriorization of violence) to which both the US and the USSR bowed. A “cold war” thus resulted in a “hot peace” (a nuclear peace). Today’s suicidal terrorists, however, don’t fear annihilation in any way. So the threat of annihilation as a means to establish an ever precarious peace doesn’t work. This means that we are challenged to look for other attempts to create peace which don’t alienate us from “the best of ourselves”. As is also clear from the research conducted by Prof. Barton, many of the recent terrorists have a history of violence and petty crime.

As is also clear from the research conducted by Prof. Barton, many of the recent terrorists have a history of violence and petty crime. . Wolfgang Palaver’s contribution for this plenary session was all the more challenging as it highlighted the inspiration Islamic tradition itself could provide to create a more peaceful world.

. Wolfgang Palaver’s contribution for this plenary session was all the more challenging as it highlighted the inspiration Islamic tradition itself could provide to create a more peaceful world.  ACU (Australian Catholic University)

ACU (Australian Catholic University)

I’d like to thank the lecturers of the concurrent sessions I went to (they were all delightful): Jonathan Cole (The Jihadist Current and the West: The Clash of Conceptuality), Susan Wright (Rekindling a Sacrificial Crisis in the Eucharist: John’s Midrashic Reversal of the ‘Manna’ Metaphors), Chloé Collier (American Presidents and Apocalyptic Discourse: Justifying Violent Foreign Policies in Times of Crisis), Suzanne Ross (Acquisitive Desire in Early Childhood: Rethinking Rivalry in the Playroom), Mathias Moosbrugger (Ignatius of Loyola and Mimetic Theory: Is it a Thing?), Wojtek Kaftanski (Mimesis as the Problem and the Cure: Kierkegaard and Girard on Human Autonomy and Authenticity), Scott Cowdell (A Five-Act Girardian Theo-Drama), David Gore (The Call to Follow Jesus), Thomas Ryba (The Sham Incarnation of the Antichrist: Some Girardian Dimensions), Jeremiah Alberg (Forbidding What We Desire; Desiring What We Are Forbidden – Krzysztof Kieslowski’s The Decalogue *), Diego Bubbio (The Self in Crisis: A Mimetic Theory of Mad Men), Paul Dumouchel (About Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing).

I’d like to thank the lecturers of the concurrent sessions I went to (they were all delightful): Jonathan Cole (The Jihadist Current and the West: The Clash of Conceptuality), Susan Wright (Rekindling a Sacrificial Crisis in the Eucharist: John’s Midrashic Reversal of the ‘Manna’ Metaphors), Chloé Collier (American Presidents and Apocalyptic Discourse: Justifying Violent Foreign Policies in Times of Crisis), Suzanne Ross (Acquisitive Desire in Early Childhood: Rethinking Rivalry in the Playroom), Mathias Moosbrugger (Ignatius of Loyola and Mimetic Theory: Is it a Thing?), Wojtek Kaftanski (Mimesis as the Problem and the Cure: Kierkegaard and Girard on Human Autonomy and Authenticity), Scott Cowdell (A Five-Act Girardian Theo-Drama), David Gore (The Call to Follow Jesus), Thomas Ryba (The Sham Incarnation of the Antichrist: Some Girardian Dimensions), Jeremiah Alberg (Forbidding What We Desire; Desiring What We Are Forbidden – Krzysztof Kieslowski’s The Decalogue *), Diego Bubbio (The Self in Crisis: A Mimetic Theory of Mad Men), Paul Dumouchel (About Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing).

I really believe that the pagans, and the abortionists, and the feminists, and the gays and the lesbians who are actively trying to make that an alternative lifestyle, the ACLU, People For the American Way – all of them who have tried to secularize America – I point the finger in their face and say “you helped this happen.”

I really believe that the pagans, and the abortionists, and the feminists, and the gays and the lesbians who are actively trying to make that an alternative lifestyle, the ACLU, People For the American Way – all of them who have tried to secularize America – I point the finger in their face and say “you helped this happen.” This is why rational people, anti-religionists, must end their timidity and come out of the closet and assert themselves. And those who consider themselves only moderately religious really need to look in the mirror and realize that the solace and comfort that religion brings you actually comes at a terrible price. […] If you belonged to a political party or a social club that was tied to as much bigotry, misogyny, homophobia, violence and sheer ignorance as religion is, you’d resign in protest. To do otherwise is to be an enabler, a Mafia wife, with the true devils of extremism that draw their legitimacy from the billions of their fellow travelers. If the world does come to an end here or wherever, or if it limps into the future, decimated by the effects of a religion-inspired nuclear terrorism, let’s remember what the real problem was: That we learned how to precipitate mass death before we got past the neurological disorder of wishing for it. That’s it. Grow up or die.

This is why rational people, anti-religionists, must end their timidity and come out of the closet and assert themselves. And those who consider themselves only moderately religious really need to look in the mirror and realize that the solace and comfort that religion brings you actually comes at a terrible price. […] If you belonged to a political party or a social club that was tied to as much bigotry, misogyny, homophobia, violence and sheer ignorance as religion is, you’d resign in protest. To do otherwise is to be an enabler, a Mafia wife, with the true devils of extremism that draw their legitimacy from the billions of their fellow travelers. If the world does come to an end here or wherever, or if it limps into the future, decimated by the effects of a religion-inspired nuclear terrorism, let’s remember what the real problem was: That we learned how to precipitate mass death before we got past the neurological disorder of wishing for it. That’s it. Grow up or die.

Florilegius/SSPL/Getty Images

Florilegius/SSPL/Getty Images

In 1973, cultural anthropologist

In 1973, cultural anthropologist  The question is whether we can be saved from our sacrificial tendencies. Since we are relational beings [or since our being is essentially relational], we can only be saved from these tendencies if we receive an identity from a being that is not at all interested in “being loved” (a being that comes from outside the human game of mutually established social expectations). This can only be a being that is not mortal, since it is mortality that leads human beings to the desire “to be loved”. If we experience the love of such a being, we can distance ourselves more and more from the desire to adjust ourselves to a self-image that seeks the approval of others. Moreover, since we diminish our auto-aggressive tendencies we will also diminish our hetero-aggressive tendencies. We will no longer defend a so-called socially acceptable self-image at the expense of others.

The question is whether we can be saved from our sacrificial tendencies. Since we are relational beings [or since our being is essentially relational], we can only be saved from these tendencies if we receive an identity from a being that is not at all interested in “being loved” (a being that comes from outside the human game of mutually established social expectations). This can only be a being that is not mortal, since it is mortality that leads human beings to the desire “to be loved”. If we experience the love of such a being, we can distance ourselves more and more from the desire to adjust ourselves to a self-image that seeks the approval of others. Moreover, since we diminish our auto-aggressive tendencies we will also diminish our hetero-aggressive tendencies. We will no longer defend a so-called socially acceptable self-image at the expense of others.  Dirk Draulans, biologist and science journalist for Belgian Knack magazine, wrote an interesting article on the question of violence in human life (Violence is deeply rooted in us – The biology of terror;

Dirk Draulans, biologist and science journalist for Belgian Knack magazine, wrote an interesting article on the question of violence in human life (Violence is deeply rooted in us – The biology of terror;  In this context Draulans refers to a thought experiment conducted by scientists who specialize in the emergence of culture. More specifically, he refers to an article in

In this context Draulans refers to a thought experiment conducted by scientists who specialize in the emergence of culture. More specifically, he refers to an article in  Quite a few scientists who participated in the thought experiment assumed that there soon would be tensions within the group, especially when food is scarce. Indeed, biologically speaking, violence is deeply rooted in us. Chimpanzees, who are models for the ape-men who were our ancestors, are ‘naturally’ violent. The world of chimpanzees is organized around the members of their own group, and neighboring groups are by definition enemies to be fought. Last year,

Quite a few scientists who participated in the thought experiment assumed that there soon would be tensions within the group, especially when food is scarce. Indeed, biologically speaking, violence is deeply rooted in us. Chimpanzees, who are models for the ape-men who were our ancestors, are ‘naturally’ violent. The world of chimpanzees is organized around the members of their own group, and neighboring groups are by definition enemies to be fought. Last year,

Scientists are struggling with the difficult balance between our propensity to violence on the one hand and our ability to cooperate on the other. This is shown by two books published last year. In

Scientists are struggling with the difficult balance between our propensity to violence on the one hand and our ability to cooperate on the other. This is shown by two books published last year. In

In a video compilation I made (on the origin of cultures) as

In a video compilation I made (on the origin of cultures) as  of Bolivia descendants of the Inca stage a festival called Tinku to receive a good harvest from ‘the mountain spirits’ (this is also shown in the video compilation, on the origin of cultures –

of Bolivia descendants of the Inca stage a festival called Tinku to receive a good harvest from ‘the mountain spirits’ (this is also shown in the video compilation, on the origin of cultures –  Wealth inequality and wealth visibility can both potentially affect levels of cooperation in a society and overall levels of economic success. Akihiro Nishi et al. use an online game to test how the two factors interact. Surprisingly, wealth inequality by itself did not damage cooperation or overall wealth as long as players do not know about the wealth of others. But when players’ wealth was visible to others, inequality had a detrimental effect.

Wealth inequality and wealth visibility can both potentially affect levels of cooperation in a society and overall levels of economic success. Akihiro Nishi et al. use an online game to test how the two factors interact. Surprisingly, wealth inequality by itself did not damage cooperation or overall wealth as long as players do not know about the wealth of others. But when players’ wealth was visible to others, inequality had a detrimental effect. I guess ‘reason’ alone doesn’t make us human. There are ‘matters of the heart’ too, guiding us to use our brains not to build weapons of mass destruction but to build ‘bridges of solidarity’…

I guess ‘reason’ alone doesn’t make us human. There are ‘matters of the heart’ too, guiding us to use our brains not to build weapons of mass destruction but to build ‘bridges of solidarity’…

It would be very interesting to create an intensified dialogue between

It would be very interesting to create an intensified dialogue between  Among other things, biology and psychology professor Paul Rozin conducted a research with children from 16 months to five years of age. This resulted in a paper first published in Appetite (7: 141-151; June 1986),

Among other things, biology and psychology professor Paul Rozin conducted a research with children from 16 months to five years of age. This resulted in a paper first published in Appetite (7: 141-151; June 1986),  “A major feature of the development of food selection is learning what not to eat.” In other words, disgust is not just a biological thing, a matter of nature. It is a cultural thing too, a matter of nurture. In yet other words, a huge part of our development concerning likes and dislikes of food lies in the imitation of others. If disgust is a matter of nurture it is also a matter of mimesis. Powerful social models have the potential to increase or decrease the disgust for certain foods. For instance, the disgust for organ meat is decreasing since it is increasingly perceived as food served to the beau monde in fancy restaurants. Organ meat thus becomes an object of mimetic desire, while at the beginning of the nineteenth century, it used to be something undesirable for the rich as it was “meat for the poor”.

“A major feature of the development of food selection is learning what not to eat.” In other words, disgust is not just a biological thing, a matter of nature. It is a cultural thing too, a matter of nurture. In yet other words, a huge part of our development concerning likes and dislikes of food lies in the imitation of others. If disgust is a matter of nurture it is also a matter of mimesis. Powerful social models have the potential to increase or decrease the disgust for certain foods. For instance, the disgust for organ meat is decreasing since it is increasingly perceived as food served to the beau monde in fancy restaurants. Organ meat thus becomes an object of mimetic desire, while at the beginning of the nineteenth century, it used to be something undesirable for the rich as it was “meat for the poor”.

The problem, of course, is that competing groups imitate this reasoning for their own particular group and thus reinforce the rivalry between each other (read René Girard’s Battling to the End in this regard, on mimetic rivalry on a planetary scale – highly recommended!).

The problem, of course, is that competing groups imitate this reasoning for their own particular group and thus reinforce the rivalry between each other (read René Girard’s Battling to the End in this regard, on mimetic rivalry on a planetary scale – highly recommended!). Not surprisingly, in light of mimetic theory, disobedience is more likely to occur:

Not surprisingly, in light of mimetic theory, disobedience is more likely to occur: People are motivated to explain their own and others’ behavior by attributing its causes to situation or disposition. Again, not surprisingly in light of mimetic theory, people show the tendency to overestimate personality factors in explaining the behavior of others, while they underestimate situational influence. On the other hand, the concept of self-serving bias points to the fact that people often do the opposite when explaining their own behavior: people try to justify themselves.

People are motivated to explain their own and others’ behavior by attributing its causes to situation or disposition. Again, not surprisingly in light of mimetic theory, people show the tendency to overestimate personality factors in explaining the behavior of others, while they underestimate situational influence. On the other hand, the concept of self-serving bias points to the fact that people often do the opposite when explaining their own behavior: people try to justify themselves. “us vs. them” social identities that are strengthened when groups compete (in-group vs. out-group;

“us vs. them” social identities that are strengthened when groups compete (in-group vs. out-group;

Several lines of evidence indicate some female competition over mating. First, at Mahale,

Several lines of evidence indicate some female competition over mating. First, at Mahale,