[KLIK HIER VOOR NEDERLANDSTALIGE VERSIE]

1.Right and Left united against “evil religion”, the common scapegoat enemy

“The Qur’an is a licence to kill.”

These words come from Filip Dewinter, one of the leading members of far-right political party Vlaams Belang, who spoke during a session of Belgium’s federal parliament (January 22, 2015).

These words come from Filip Dewinter, one of the leading members of far-right political party Vlaams Belang, who spoke during a session of Belgium’s federal parliament (January 22, 2015).

Dewinter sounds a lot like the members of Islamic State (IS) whose conclusion on the issue of beheadings drawn from their reading of the Qur’an goes as follows:

“The Qur’an justifies these killings.”

It seems a bit ironic, but Dewinter and the members of Islamic State actually agree on the so-called “true nature of Islam”. Dewinter literally echoes the words of Hussein bin Mahmoud, a Jihadi cleric, who said (from an article posted August 21, 2014 on the Shumoukh Al-Islam forum):

“Islam is a religion of power, fighting, jihad, beheading and bloodshed.”

“Islam is a religion of power, fighting, jihad, beheading and bloodshed.”

For some it’s a small step to go from this so-called “true, violent nature of Islam” to the so-called “true, violent nature of religion in general”. That’s in fact an even more extreme version of Dewinter’s discourse and, once again ironically, if Dewinter would deliver that statement he would find some allies on the far-left side of the political spectrum (heir to Marx’s idea that “religion is the opium of the people”). As the French would say, eventually “Les extrêmes se touchent”, the extremes meet one another.

In fact, many atheists today believe (hmm, “atheists believe…”), whether from the political “right” or “left”, that “religion must die for mankind to live” (Bill Maher in the mockumentary Religulous). Yet many of them claim to nevertheless have respect for people who believe in God, although some of them make a distinction between “respecting the people” (for instance Muslims) and “disrespecting their belief” (for instance Islam – And then you get things like: “I’m not saying you, as a Muslim, are violent, I’m saying Islam is violent!”). That’s a bit like some Catholics who say that they don’t have any problems with homosexuals, only with homosexuality (“I’m not saying you are perverted, I’m saying your sexuality is!”). For more on this analogy, see below (chapter 4 of this post).

Anyway, as René Girard points out in his mimetic theory, to sacrifice what is considered to bring about violent mayhem – a “scapegoat” – is a mechanism as old as humanity itself. In the words of Karen Armstrong:

Anyway, as René Girard points out in his mimetic theory, to sacrifice what is considered to bring about violent mayhem – a “scapegoat” – is a mechanism as old as humanity itself. In the words of Karen Armstrong:

As one who speaks on religion, I constantly hear how cruel and aggressive it has been, a view that, eerily, is expressed in the same way almost every time: “Religion has been the cause of all the major wars in history.” I have heard this sentence recited like a mantra by American commentators and psychiatrists, London taxi drivers and Oxford academics. It is an odd remark. Obviously the two world wars were not fought on account of religion . . . Experts in political violence or terrorism insist that people commit atrocities for a complex range of reasons. Yet so indelible is the aggressive image of religious faith in our secular consciousness that we routinely load the violent sins of the 20th century on to the back of “religion” and drive it out into the political wilderness.

2. Mimetic doubling of religious fascism by some (“liberal”) humanists

Our ancestors attributed all sorts of violence to the gods or, more generally speaking, “a sacred realm”. In order to prevent “the wrath of the gods” – experienced in violent rivalry tearing a community apart, but also in the violence of a pandemic or a natural disaster – and receive “peace and order from the gods”, ancient cultures held on to different systems of taboos and rituals. The taboos on violence and the things that were considered to bring about violence could only be transgressed in rituals and sacrificial rituals (which included wars and ceremonial battles). The ritualistic violence of sacrifices, ceremonial battles and wars was considered permissible and necessary violence, sanctioned by the gods, and ultimately aimed at the establishment of a new peace and order. In short, sacrifice – “the good of a stabilized violence” – was considered necessary to expel “the evil of destabilizing violent mayhem”.

Some atheists, dreaming of a “non-religious” world, might pat themselves on the back now and point to the backward nature of the religiously motivated sacrifices by Islamic State:

• Clearly the sacrificial violence of Islamic State (whether suicidal or aimed at others) is primitive and barbaric, rooted in a pre-modern world-view when people could still believe that violence comes from a non-human realm, from a divine or sacred realm.

In short, according to Islamic State, God is violent (although he can grant us peace as well, if we are willing to live according to his rules).

• By using God as a justification for sacrifices the members of Islamic State cowardly try to avoid their own responsibility and accountability for the violent acts they commit. Moreover, the members of Islamic State make themselves dependent on a set of so-called divine rules (sharia), unable to even take responsibility for their own lives as a whole.

In short, the members of Islamic State use God as a scapegoat, blaming God for the violence they commit themselves.

In this regard one would expect that atheists see religion for what it is – at least in this context: religious beliefs and practices are (imaginary) answers to the problem of human violence. Religion is a consequence of the need to deal with our own (tendencies towards) violence. Sure many “islamists” in Europe grew up without religion, or without the religion of their parents (hence the generation gap between some Muslim parents and their radicalized children). The sudden “conversion” of young people in Europe and their violent opinions on Islam can therefore indeed be understood as a consequence of certain frustrations and aggressive tendencies, more than as a cause of those frustrations and aggressive tendencies. The atheist analysis of religiously motivated violence should therefore read as follows:

• In case human beings use violence, this violence comes from a human realm. Violence is not divine or sacred, it is human.

In short, according to atheism, humans are violent (although we can be peaceful as well, of course).

• Atheists claim that God does not exist. A creature that does not exist, cannot be responsible for anything, let alone for the violent acts performed by humans themselves. Humans cannot blame anything other than themselves for violence.

In short, according to atheists, humans carry responsibility for violence.

However, a strange thing occurs in some atheist quarters. The analysis of religiously motivated violence often goes like this:

• In case religious people use violence, it is caused by their religion. Since no man is born with a religion, it is clear that the roots of religiously motivated violence lie outside man [as if religion comes from Mars or something, as if religion is alien to (“the true nature of”) man?!]. Of course, it’s true as well that no man is born with any particular language, but the big difference is that we need languages to communicate and work together in order to survive, while we don’t need religion – on the contrary, religion might prevent the survival of the human race! [Note: to determine the value of something by measuring its supposed “usefulness” is not “neutral”, it’s already dependent on a certain outlook on life or world-view].

• In case religious people use violence, it is caused by their religion. Since no man is born with a religion, it is clear that the roots of religiously motivated violence lie outside man [as if religion comes from Mars or something, as if religion is alien to (“the true nature of”) man?!]. Of course, it’s true as well that no man is born with any particular language, but the big difference is that we need languages to communicate and work together in order to survive, while we don’t need religion – on the contrary, religion might prevent the survival of the human race! [Note: to determine the value of something by measuring its supposed “usefulness” is not “neutral”, it’s already dependent on a certain outlook on life or world-view].

In short, following this type of reasoning, religion is violent.

• According to some atheists, religion is not a consequence of man’s violent tendencies. On the contrary, religion is one of the main causes of man’s violence. Human violence does not cause religion or the need for religious justifications. It’s the other way around: religion causes human violence.

In short, according to some atheists, religion is to blame for violence.

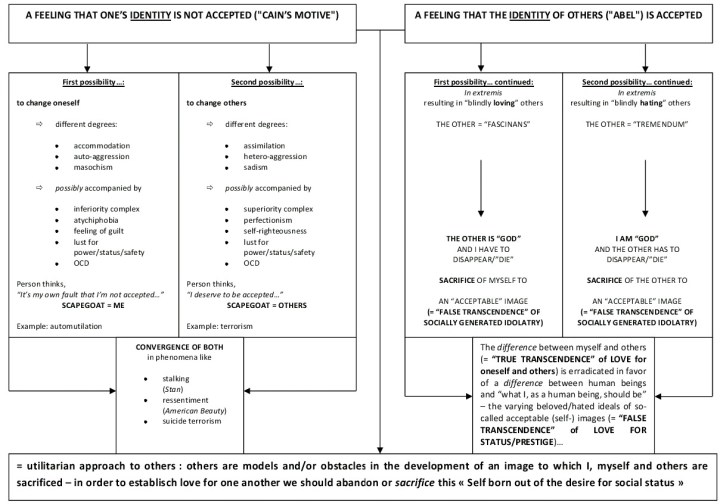

There is a striking resemblance between the way in which some religious fanatics view the reality of religiously motivated violence and the views of some atheists. In the words of René Girard, some atheists are imitative twins or mimetic doubles to their intolerant religious counterparts.

There is a striking resemblance between the way in which some religious fanatics view the reality of religiously motivated violence and the views of some atheists. In the words of René Girard, some atheists are imitative twins or mimetic doubles to their intolerant religious counterparts.

Both groups believe that the roots of violence lie in a realm which somewhat transcends humans (a supernatural or perverted realm respectively). “God orders violence.” Or, “religion causes violence”.

Both groups also share a common view on how to achieve a peaceful world: humans should live according to their “true” nature.

The members of Islamic State believe that humans who live without belief in God (or, more extreme even, without belief in the “true” God) invoke the “violent wrath of God”. Thus peace is only possible if the “infidels” are willing to sacrifice their pagan or secular opinions and lifestyle, and convert to God. If they are unwilling to sacrifice their sinful way of life, they should be sacrificed in order to prevent more “violent wrath of God”.

Some atheists believe that humans who live with belief in God are sustaining some of the major conditions that invoke violence. In the words of Bill Maher (again from his mockumentary Religulous):

Religion is dangerous… This is why rational people, anti-religionists, must end their timidity and come out of the closet and assert themselves. And those who consider themselves only moderately religious really need to look in the mirror and realize that the solace and comfort that religion brings you actually comes at a terrible price.

Thus peace is only possible if “theists” are willing to sacrifice their barbaric and primitive opinions and lifestyle, and convert to atheism. After all, according to these atheists, no human being is born with a religion, hence the truly “natural” state of man is non-religious. Note: the zealous advocates of an “Enlightened Reason” that is supposedly very different from “all those fear-rooted religions” constantly refer to “the dangers of religion”. Quite ironic. Ah, well…

3. The Fascism of Anti-religious Utopians – Joël De Ceulaer joins Filip Dewinter

The atheist camp might point to a difference that still seems to exist between “theists” and “atheists”. Although some atheists ask theists to consider abandoning their beliefs, they don’t use any violence against people. At best they use “verbal violence” against “weird ideas” or “weird behaviors” – you know, again, this is analogous to some Catholics who tolerate gay people while condemning homosexuality. They don’t sacrifice people, unlike some theists. Some regard this as a confirmation of their claim that it is really religion that drives people to violence. Moreover, most atheists are able to tolerate religious people, even if their religion is the cause of so much violence! Surely, atheism leads to a better, more tolerant world, no?

The so-called “humanist” atheist tolerance towards “theists” often comes across a bit strange. The atheist who stresses that the belief of his fellow man “is not a problem” to him actually implies that “this could be an issue in normal circumstances”. As if it’s not self-evident. As if the atheist is in the superior position from which he grants the theist the right to be who he is or wants to be. What if people who claim tolerance towards gay people would stress that they don’t have any problems with gay people every time they meet someone who is gay? A bit odd…

But, oh, I forgot to mention other signs of tolerance among atheists. Many of them have no problem whatsoever to attend Turkish restaurants run by Muslims. Also, many atheists already paid a visit to a mosque. Of course none of them would consider conversion to Islam a reasonable option, but look, even if they know that they are in the superior, more progressed and enlightened position, they still take the time to get to know a little bit more about a “less advanced” culture.

Despite the seeming tolerance, intolerance towards religious people is never far in some atheist quarters. In the wake of the terrorist attacks on Charlie Hebdo, Belgian journalist Joël De Ceulaer expands the Islamophobia of Filip Dewinter to religiophobia. Unlike Dewinter, who still somewhat tried to make a distinction between the Qur’an and Muslims, De Ceulaer immediately becomes personal. The journalist and his ideological friends want to “get rid of all merchants of religion and other world-views” in Belgian schools and replace their respective curricula by one, supposedly “neutral” curriculum on “world-views, ethics and philosophy” (Dutch: “LEF – Levensbeschouwingen, Ethiek, Filosofie”), taught by “neutral” teachers. It’s still not clear what a “neutral” use of rationality and science to study different world-views actually looks like, but De Ceulaer (interviewed on Belgian television program Reyers Laat, January 19, 2015) is convinced that:

Despite the seeming tolerance, intolerance towards religious people is never far in some atheist quarters. In the wake of the terrorist attacks on Charlie Hebdo, Belgian journalist Joël De Ceulaer expands the Islamophobia of Filip Dewinter to religiophobia. Unlike Dewinter, who still somewhat tried to make a distinction between the Qur’an and Muslims, De Ceulaer immediately becomes personal. The journalist and his ideological friends want to “get rid of all merchants of religion and other world-views” in Belgian schools and replace their respective curricula by one, supposedly “neutral” curriculum on “world-views, ethics and philosophy” (Dutch: “LEF – Levensbeschouwingen, Ethiek, Filosofie”), taught by “neutral” teachers. It’s still not clear what a “neutral” use of rationality and science to study different world-views actually looks like, but De Ceulaer (interviewed on Belgian television program Reyers Laat, January 19, 2015) is convinced that:

“It is a train that cannot be stopped.”

Wow. A neutral curriculum as an antidote to the violence of religious fanatics. It seems De Ceulaer is one of those utopistic atheists John Gray writes about in an article for The New Statesman (October 1, 2014):

The idea that religion is fading away has been replaced in conventional wisdom by the notion that religion lies behind most of the world’s conflicts. Many among the present crop of atheists hold both ideas at the same time. They will fulminate against religion, declaring that it is responsible for much of the violence of the present time, then a moment later tell you with equally dogmatic fervour that religion is in rapid decline. Of course it’s a mistake to expect logic from rationalists. More than anything else, the evangelical atheism of recent years is a symptom of moral panic. Worldwide secularisation, which was believed to be an integral part of the process of becoming modern, shows no signs of happening. Quite the contrary: in much of the world, religion is in the ascendant. For many people the result is a condition of acute cognitive dissonance.

As I already mentioned, both religious and anti-religious fanatics claim that religiously motivated violence is ultimately rooted in a realm that transcends human nature (a supernatural or alienating/perverted realm respectively). Both camps also claim to have access to “The Truth”. The members of Islamic State claim to possess the source of full knowledge (that is, within the limits of human possibilities) of “what’s true” and “what’s right”, revealed to them in the Qur’an. De Ceulaer and his lobbyists also claim to possess the source of full knowledge (again, within the limits of human possibilities) of “what’s true” and “what’s right”, namely reason and science.

In short, both religious and anti-religious fanatics are convinced that they can occupy a viewpoint which transcends “all particular viewpoints”. Call it Divine, call it Neutral – I call it Totalitarian and Idolatrous, implying the self-divinization of Man and the disappearance of any true belief in a transcendent realm. One can expect OBJECTIVITY from teachers of religion and world-views, NOT NEUTRALITY. Atheist, Buddhist, Christian or Islamic teachers who present Christianity from the viewpoints of, say, Karl Rahner, George Coyne or James Alison (all Catholic theologians) will tell similar things to their students if they’re objective. They will be able to confront those views with the views of fundamentalists like Jerry Falwell and Pat Robertson. With the views of past Catholics like Benedict of Nursia, Francis of Assisi or Ignatius of Loyola. They will be able to point to similarities and differences. They will also create the possibility of a dialogue with the perspectives and cultural background of their students. A so-called “DIVINE” or “NEUTRAL” viewpoint does not call for dialogue. It demands to be accepted without any discussion, and is a form of mind control or brainwashing.

I’m one of those so-called “merchants” De Ceulaer refers to. What am I selling, according to him? Lies – maybe even deliberately? Violence? When will I be replaced by a colleague who teaches from the “neutral”, state-imposed viewpoint? Clearly, this has to be done – and I will give De Ceulaer one more reason to demonize the “merchants” – because I will never ever claim or agree to speak from a so-called “neutral” perspective. That would be the biggest lie! I’m trying to teach what Christianity is all about from a Catholic perspective (“a”, not “the”). This should enable my students to form their own opinions on Catholicism, but also on other types of Christianity, and other religions and world-views, because I’m able to point to differences and similarities from my particular perspective. Rest assured, it is not my task to try to convert people to Catholicism, it is my task to enable them to form their own opinions on things they very often know nothing about.

I’m one of those so-called “merchants” De Ceulaer refers to. What am I selling, according to him? Lies – maybe even deliberately? Violence? When will I be replaced by a colleague who teaches from the “neutral”, state-imposed viewpoint? Clearly, this has to be done – and I will give De Ceulaer one more reason to demonize the “merchants” – because I will never ever claim or agree to speak from a so-called “neutral” perspective. That would be the biggest lie! I’m trying to teach what Christianity is all about from a Catholic perspective (“a”, not “the”). This should enable my students to form their own opinions on Catholicism, but also on other types of Christianity, and other religions and world-views, because I’m able to point to differences and similarities from my particular perspective. Rest assured, it is not my task to try to convert people to Catholicism, it is my task to enable them to form their own opinions on things they very often know nothing about.

While I wait for De Ceulaer’s unstoppable train of “a state-imposed neutral viewpoint” (I thought we were passed the violence – indeed! – of totalitarian atheist regimes in Europe), there’s another train coming as well. De Ceulaer’s words inadvertently made me think of a statement by Islamist preacher Anjem Choudary, who was interviewed by CNN-host Brian Stelter (on the August 31, 2014 edition of the program Reliable Sources):

“I believe that the Sharia is the best way of life. I believe that one day it will come to America and the rest of the world.”

Apparently we are living in “end times”.

The apocalyptic battle is on. Which train will win?

4. Some more words on the religion/homosexuality analogy

Some atheists say:

“No man is born religiously, religion is a perversion of human nature.”

Note: some argue that the inclination to believe in God can be situated in the brain – since when are brains “unnatural”? Of course, it is not because something is “natural” that it is “good” – maybe pedophilia is also a natural inclination, that doesn’t mean it’s good. It is quite funny, though, how some atheists argue that homosexuality should be allowed because of a “gay gene”, while at the same time they argue that theists should no longer allow their faith because of a “God gene”.

Some religious people (but there are atheists as well who think like this) say:

“No man is born gay, homosexuality is a perversion of human nature.”

Well, of course no one is born with a particular gay partner and a particular way to experience his homosexuality, but the homosexual inclination is there. And no, lovingly or passionately talking about a partner is not synonymous with an attempt to convince other people that they should also start an intense relationship with that partner. They’re still free to choose their own partners, but at least they get a testimony on what it means to be in a relationship with someone.

Are there homosexuals with a distorted, disrespectful sexual life (disrespectful towards other gays)? Sure, like there are heterosexuals with a distorted sexuality; this doesn’t mean that homosexuality as such is a perversion.

Well, of course no one is born with a particular religion and a particular way to experience his sense of awe for what transcends human life (atheists have this spiritual experience as well as theists), but we could argue that a “religious inclination” is there. And no, lovingly or passionately talking about a religion is not synonymous with an attempt to convince other people that they should also start an intense relationship with that religion. They’re still free to choose their own religions, but at least they get a testimony on what it means to be religious.

Most sexual relationships don’t involve rape. The same reasoning goes for religion: most religious beliefs and conducts don’t involve violence. Of course, certain media and polarizing populists often don’t like “the ordinary” – they go for “the sensational”.

Are there religious people with a distorted, disrespectful religious life (disrespectful towards other people)? Sure, like there are atheists with a world-view that encourages disrespectful attitudes towards other people; this doesn’t mean that every religion or world-view is a perversion.

Anyway, some fundamentalist Christians blame homosexuals for some of the main evils in the world (click here for my previous post on this), like some atheists blame religious people (“people with gods kill people”) for some of the main evils in the world. That’s why De Ceulaer says: “Get rid of the merchants of religion in our schools!” As if we’re perverting the youth. This mirrors the reasoning of some religious fundamentalists who ask to “Get rid of the merchants of sexual perversion – homosexuality – in our schools!” As if gays are perverting the youth.

The paradox is that so-called “anti-religionists” create a new religious structure according to a scapegoat mechanism. However, there are enough spiritual minds (whether theist or atheist) who can free us from our scapegoating impulses (whether theist or atheist).

Conclusion:

Every ideological, non-spiritual religion its scapegoat, whether atheist or theist?

The noise of which spread everywhere around;

The noise of which spread everywhere around;

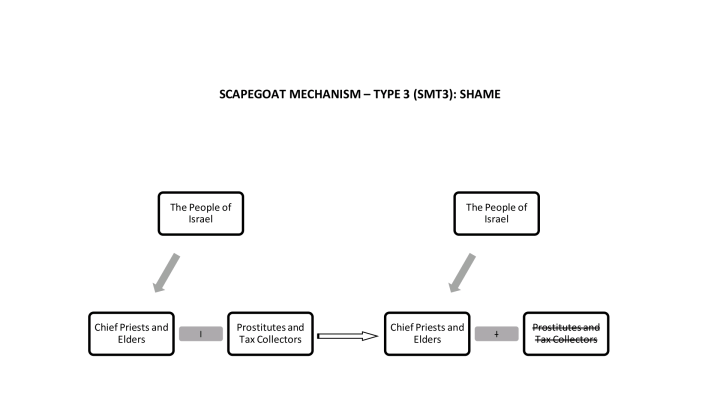

Jesus said to them, “Truly I tell you, the tax collectors and the prostitutes are entering the kingdom of God ahead of you. For John came to you to show you the way of righteousness, and you did not believe him, but the tax collectors and the prostitutes did. And even after you saw this, you did not repent and believe him.”

Jesus said to them, “Truly I tell you, the tax collectors and the prostitutes are entering the kingdom of God ahead of you. For John came to you to show you the way of righteousness, and you did not believe him, but the tax collectors and the prostitutes did. And even after you saw this, you did not repent and believe him.”

Eventually, because Christianity gradually destroyed the authority of the God(s) of traditional religion, the hierarchical nature of society was no longer accepted. The French revolutionists cried égalité! and the idea of a principally egalitarian society was born – all human beings (should) have equal rights. This meant that mimetic desire became less suppressed, and this led to the emancipation of different groups in western society. First, factory workers started to compare themselves to the wealthy factory owners. Why shouldn’t the workers enjoy the same rights as their employers? In other words, the workers started to desire what their employers possessed and this mimetic desire could no longer be suppressed. Second came the emancipation of women. They started to desire the rights owned by their male counterparts. Third came the full revolt of blacks (heir to black slaves) in the US. Then came the emancipation of gay people who compared themselves to heterosexuals and desired and demanded equal rights… Finally, together with the aforementioned emancipatory movements, the emancipation of children and youngsters (and the phenomenon of a so-called youth culture) poses new challenges to our personal and social self-understanding. There’s a strange interaction going on, with a rivalry between young and old to become each other’s model or example. [

Eventually, because Christianity gradually destroyed the authority of the God(s) of traditional religion, the hierarchical nature of society was no longer accepted. The French revolutionists cried égalité! and the idea of a principally egalitarian society was born – all human beings (should) have equal rights. This meant that mimetic desire became less suppressed, and this led to the emancipation of different groups in western society. First, factory workers started to compare themselves to the wealthy factory owners. Why shouldn’t the workers enjoy the same rights as their employers? In other words, the workers started to desire what their employers possessed and this mimetic desire could no longer be suppressed. Second came the emancipation of women. They started to desire the rights owned by their male counterparts. Third came the full revolt of blacks (heir to black slaves) in the US. Then came the emancipation of gay people who compared themselves to heterosexuals and desired and demanded equal rights… Finally, together with the aforementioned emancipatory movements, the emancipation of children and youngsters (and the phenomenon of a so-called youth culture) poses new challenges to our personal and social self-understanding. There’s a strange interaction going on, with a rivalry between young and old to become each other’s model or example. [