OUR WORLD, A WORLD OF CHILD NEGLECT?

Basically, there are three types of child neglect:

- Indifference (rarely if ever paying attention to a child)

- Denigration (paying attention in an all too negative way)

- Adoration (paying attention in an all too positive way)

A child who grew up in an indifferent environment is prone to seek attention from people just for the sake of getting attention. Needless to say, they can easily fall into the hands of malicious manipulators (from gurus to pedophiles) who meet the child’s need “to feel special” and “to be saved and taken care of”.

A child who is denigrated time and again if he does not live up to the expectations of his educators will develop a sense of unworthiness. He will feel ashamed of himself or will even learn to hate himself. Later on in life, he will do anything in his power not to fail in the eyes of others. He might even develop a perverted sense of pride, hiding his sense of unworthiness behind a supposedly socially acceptable self-image. Fear of failure (atychiphobia) then reveals itself as a built-in desire for perfection.

A child who is constantly adored will develop a false sense of superiority. If he fails, he will sometimes feel ashamed of himself or hate himself, but most of the time he will blame others for his failure. In other words, he will create scapegoats because he is not able to take responsibility for his own mistakes. His educators made him believe that he is perfect, and of course he tries to satisfy this built-in desire for perfection.

Indifference, denigration and/or adoration: in all three cases the difference between the wishes of the child’s environment and the child himself are eradicated. The child is forced to adapt to the unrealistic wishes of his environment and therefore is not able to accept himself as he actually is. In other words, because the child has learned to be guided by his desire for recognition, he is not able to love himself (he subjects himself to an unrealistic but supposedly socially acceptable self-image) and he is not able to love others (he only approaches others to satisfy his need for recognition, and not as ends in themselves). The child will fear saying “sorry” because he has learned that the world does not allow for failure…

Ever met those parents who said to their child “You can be a doctor” or “You can be a sports champion” when in fact their child had other talents? Ever met those parents who convinced themselves, their child and part of their environment that “The teacher” or “The coach” was to blame for whatever went wrong when the child did not live up to the parents’ expectations?

OUR ATHEIST WORLD, A WORLD OF GODS AND FAIRY TALES?

Yep, it seems the more atheist we become, the more we lose touch with reality, beginning with the reality of ourselves. We bow to the idols we have made from ourselves, the false “monstrous” or “divine” images about ourselves we have learned to love, instead of accepting ourselves and our limits as human beings. If religion is defined as “opium of the masses” (Karl Marx, 1818-1883), then our atheist world is full of it. We have replaced a perverted version of Christianity, one that made us believe we could enter “paradise” if we were willing to make sacrifices, with “secular” dreams of paradise and perfection.

Yep, it seems the more atheist we become, the more we lose touch with reality, beginning with the reality of ourselves. We bow to the idols we have made from ourselves, the false “monstrous” or “divine” images about ourselves we have learned to love, instead of accepting ourselves and our limits as human beings. If religion is defined as “opium of the masses” (Karl Marx, 1818-1883), then our atheist world is full of it. We have replaced a perverted version of Christianity, one that made us believe we could enter “paradise” if we were willing to make sacrifices, with “secular” dreams of paradise and perfection.

However, the so-called “Christian” attitude to merely confess our sins to God and pay for them by denigrating ourselves (physically and/or mentally) as a “sacrifice to God” in order to become “perfect” and to get God’s recognition, is really a betrayal of the Gospel and of Christianity. Jesus makes it clear: “No one is good – except God alone.” (Mark 10:18). In other words, we should not want to be someone we are not. Indeed, we are not perfect. Jesus also makes clear that prayers and sacrifices should not be used to escape moral responsibilities. If you go to confession and use God’s forgiveness to recreate a so-called acceptable self-image, without actually doing something about the evil you’ve committed, you’re perverting the nature of confession. Confession should serve love for one’s neighbor, and not one’s need for recognition. That’s why Jesus says (Matthew 5:23-24): “If you are offering your gift at the altar and there remember that your brother or sister has something against you, leave your gift there in front of the altar. First go and be reconciled to them; then come and offer your gift.” In other words, sacrifice not as a “do ut des” or “quid pro quo”, but as a free gift of gratitude for what’s already established. Jesus transforms laws and legislations, bringing them back to their true goal against possible perversions (That’s why he says, “Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them.” – Matthew 5:17). The law should serve man and enable love for one’s neighbor, it should not be used against man and love (see Matthew 22:34-40 and Matthew 12:1-14).

JESUS CHRIST, BACK TO LIFE, BACK TO REALITY?

The realization that you’re not perfect (and that you don’t have to be) will help you to deal with the imperfections of others as well. That’s why Jesus constantly asks people to realize their own shortcomings. “He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her”, he says to the crowd that wants to stone a woman accused of adultery (John 8:7). And in the Lord’s prayer he asks us to think of our own trespasses, in order to be able to forgive others (Matthew 6:12): “Forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us.” The sooner you are able to admit some minor mistakes, the better you will avoid scapegoat mechanisms. On the other hand, if you want to protect an unrealistic yet so-called admirable self-image, you will use one lie after the other and blame others for what’s bad and for what goes wrong, instead of taking responsibility yourself.

The realization that you’re not perfect (and that you don’t have to be) will help you to deal with the imperfections of others as well. That’s why Jesus constantly asks people to realize their own shortcomings. “He that is without sin among you, let him first cast a stone at her”, he says to the crowd that wants to stone a woman accused of adultery (John 8:7). And in the Lord’s prayer he asks us to think of our own trespasses, in order to be able to forgive others (Matthew 6:12): “Forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us.” The sooner you are able to admit some minor mistakes, the better you will avoid scapegoat mechanisms. On the other hand, if you want to protect an unrealistic yet so-called admirable self-image, you will use one lie after the other and blame others for what’s bad and for what goes wrong, instead of taking responsibility yourself.

People hurt each other. We’re not perfect in our love. We even hurt those we love the most. Every week we say stuff we probably mean less offensive because we’re too easily irritated by each other. Jesus thus is more realist than ever when Peter asks him a question about forgiveness (Matthew 18:21-22): “Lord, how many times shall I forgive my brother or sister who sins against me? Up to seven times?” Jesus answered, “I tell you, not seven times, but seventy times seven.”

People hurt each other. We’re not perfect in our love. We even hurt those we love the most. Every week we say stuff we probably mean less offensive because we’re too easily irritated by each other. Jesus thus is more realist than ever when Peter asks him a question about forgiveness (Matthew 18:21-22): “Lord, how many times shall I forgive my brother or sister who sins against me? Up to seven times?” Jesus answered, “I tell you, not seven times, but seventy times seven.”

Of course, truth hurts. So more often than not, we flee from the truth about ourselves. We rather think about ourselves in a heroic fashion. We identify with “good” characters in Hollywood movies. The apostle Peter also thinks of himself as a hero during the last supper before Jesus is arrested, while Jesus – that hyper-realistic “Christ” man – tries to bring him down to earth (Matthew 26:33-35): Peter said, “Even if all fall away on account of you, I never will.” “Truly I tell you,” Jesus answered, “this very night, before the rooster crows, you will disown me three times.” But Peter declared, “Even if I have to die with you, I will never disown you.” And all the other disciples said the same.

The Gospel eventually shows man as he is, and not as he romantically dreams himself to be. It is easy to be morally indignant about reports of child abuse in the newspaper. It turns out to be much more difficult to handle such delicate matters when we’re directly confronted with them. Maybe then we’re not as heroic as we thought we’d be. The apostle Peter discovers the not so heroic truth about himself after Jesus is arrested (Matthew 26:69-75): Now Peter was sitting out in the courtyard, and a servant girl came to him. “You also were with Jesus of Galilee,” she said. But he denied it before them all. “I don’t know what you’re talking about,” he said. Then he went out to the gateway, where another servant girl saw him and said to the people there, “This fellow was with Jesus of Nazareth.”He denied it again, with an oath: “I don’t know the man!”After a little while, those standing there went up to Peter and said, “Surely you are one of them; your accent gives you away.” Then he began to call down curses, and he swore to them, “I don’t know the man!” Immediately a rooster crowed. Then Peter remembered the word Jesus had spoken: “Before the rooster crows, you will disown me three times.” And he went outside and wept bitterly.

The Gospel eventually shows man as he is, and not as he romantically dreams himself to be. It is easy to be morally indignant about reports of child abuse in the newspaper. It turns out to be much more difficult to handle such delicate matters when we’re directly confronted with them. Maybe then we’re not as heroic as we thought we’d be. The apostle Peter discovers the not so heroic truth about himself after Jesus is arrested (Matthew 26:69-75): Now Peter was sitting out in the courtyard, and a servant girl came to him. “You also were with Jesus of Galilee,” she said. But he denied it before them all. “I don’t know what you’re talking about,” he said. Then he went out to the gateway, where another servant girl saw him and said to the people there, “This fellow was with Jesus of Nazareth.”He denied it again, with an oath: “I don’t know the man!”After a little while, those standing there went up to Peter and said, “Surely you are one of them; your accent gives you away.” Then he began to call down curses, and he swore to them, “I don’t know the man!” Immediately a rooster crowed. Then Peter remembered the word Jesus had spoken: “Before the rooster crows, you will disown me three times.” And he went outside and wept bitterly.

Ah, the things we do for our reputation, for power, for survival… Jesus warns us not to enslave ourselves to so-called socially acceptable self-images (“idols”) in order to gain recognition. When you force yourself to be someone you are not because certain people made you believe that this is your “ticket to paradise”, your life will become a living hell of frustration, jealousy and hypocrisy. Indeed Jesus is right when he says, “whoever wants to save their life will lose it” (Matthew 16:25). And when he says (Matthew 6:1-2): “Be careful not to practice your righteousness in front of others to be seen by them. If you do, you will have no reward from your Father in heaven. So when you give to the needy, do not announce it with trumpets, as the hypocrites do in the synagogues and on the streets, to be honored by others. Truly I tell you, they have received their reward in full.”

If you want success because of success itself, you will never find love and joy for what you’re doing. If a student wants good grades and academic recognition more than an understanding of his courses, he will never find joy in what he’s actually studying (for more on this, click here or click here). The scientist whose goal it is to win the Nobel Prize won’t get it. It’s the scientist who has learned to be passionate [yep, we have to learn to love – because love is relating to what’s other than ourselves, and therefore goes beyond our needs] about his topic who might eventually get the Nobel Prize as a consequence of his actions – and not as an ultimate goal. So we should not force ourselves to be someone we are not in order to get into heaven. We shouldn’t be like the workaholic who becomes a slave of a “high society lifestyle”. We shouldn’t be like the drug addict who believes that he should flee from himself in a frenzy to be in paradise. We shouldn’t believe that “doing what we please” is the highest form of freedom – the drug dealer wants nothing more than to become the false messiah who satisfies the supposedly very own needs he has inflicted upon his clients.

We should try to find ourselves. We should try to respect ourselves and accept our limitations in this atheist world full of unrealistic idols. We should try to discover our calling. Jesus teaches that we find ourselves if we dare associate ourselves with the social outcasts. Indeed, if Peter would have defended Jesus after the latter’s arrest, Peter wouldn’t have lost himself to a so-called socially acceptable image. Jesus rightly says, “whoever loses their life for me [meaning the Victim of people who look for social recognition and who tend to blame others for their own failures] will find it” (Matthew 16:25). If Peter would have imitated Jesus (who constantly took sides with social outcasts and scapegoats), he wouldn’t have participated in the death of Jesus. Then Peter would have discovered that he’s not merely a child of his social environment and a slave to a socially acceptable self-image (or idol), but also a child of God.

As intrinsically relational beings, our identities are given to us in relationships to others. Since no human being is able to love us completely for who we are, only a creature that is “also other than human” is able to truly give us to ourselves. If we believe that this man-made world is the only possible world, we will do everything to gain recognition in this world, force ourselves to be who we are not, and be dead before we have lived – unable to truly love the social outcast. To discover God is to discover Love (see 1 John 4: “God is Love”). It is to discover ourselves as well as our neighbors. 1 John 3,14: “We know that we have passed from death to life, because we love each other. Anyone who does not love remains in death.” The choice is ours: whether we believe we’re merely children of man-made idols, guided by our desire for recognition, or we believe we’re also children of Love… Max Scheler (1874-1928), once again:

Man believes either in a God or in an idol…

If we learn to love ourselves and be genuinely interested in the things we do, we will be rewarded eventually – the joy of doing those things will be a reward in itself. Success or “heaven” will be the consequence of love for ourselves and others and not an end in itself. In the words of Jesus, we should find God’s kingdom and righteousness first, and everything else will come…

“So do not worry, saying, ‘What shall we eat?’ or ‘What shall we drink?’ or ‘What shall we wear?’ For the pagans run after all these things, and your heavenly Father knows that you need them. But seek first his kingdom and his righteousness, and all these things will be given to you as well. Therefore do not worry about tomorrow, for tomorrow will worry about itself. Each day has enough trouble of its own.” (Matthew 6:31-34)

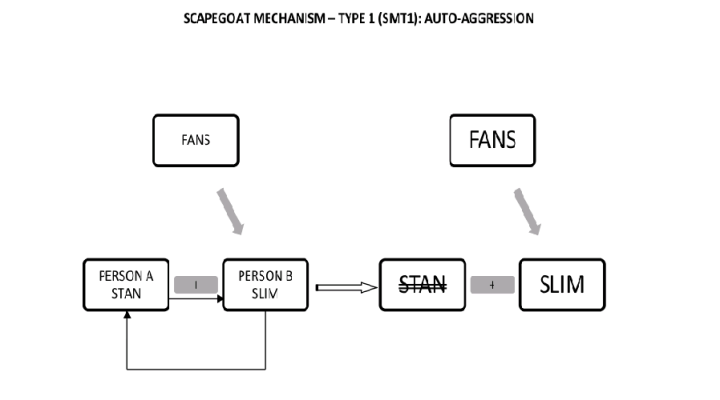

The story of Cain and Abel (in the book of Genesis) is compared to the story of Stan (by Eminem) to illustrate what I’ve called types 1 and 2 of the scapegoat mechanism. Cain and Abel is an example of the second type of scapegoat mechanism, namely hetero-aggression. Stan is an example of the first type of scapegoat mechanism, namely auto-aggression. By the way, the comparison between Cain and Stan is a translation of a text that first appeared in Dutch in my book Vrouwen, Jezus en rock-‘n-roll (Averbode, 2009).

The story of Cain and Abel (in the book of Genesis) is compared to the story of Stan (by Eminem) to illustrate what I’ve called types 1 and 2 of the scapegoat mechanism. Cain and Abel is an example of the second type of scapegoat mechanism, namely hetero-aggression. Stan is an example of the first type of scapegoat mechanism, namely auto-aggression. By the way, the comparison between Cain and Stan is a translation of a text that first appeared in Dutch in my book Vrouwen, Jezus en rock-‘n-roll (Averbode, 2009). “… but you must rule over it…”

“… but you must rule over it…”

During that time Kaiser Wilhelm II had the biggest land army in the world and he invested some of his private money to buy and develop cannons. Growing up he had seen the richness of the British Empire and he tried to emulate this for his own country. Therefore he supported Germany’s naval expansion and eventually did obtain an empire in Africa and the western Pacific, although not as large as he wanted (on the right, Wilhelm II visiting the African Colonies). The so-called Great Naval Race of the early 1900’s was an extension of his need to do better than his relatives by trying to build more battleships than the British Royal Navy had.

During that time Kaiser Wilhelm II had the biggest land army in the world and he invested some of his private money to buy and develop cannons. Growing up he had seen the richness of the British Empire and he tried to emulate this for his own country. Therefore he supported Germany’s naval expansion and eventually did obtain an empire in Africa and the western Pacific, although not as large as he wanted (on the right, Wilhelm II visiting the African Colonies). The so-called Great Naval Race of the early 1900’s was an extension of his need to do better than his relatives by trying to build more battleships than the British Royal Navy had.