- FEMME DE LA RUE

Sofie Peeters made quite an impression when she launched her student film Femme de la Rue. Not only in her native country Belgium, but also across the borders. Her autobiographical, short documentary film addresses a certain kind of sexism in the streets of Brussels. Peeters is seen walking around the neighborhood that used to be her home while attending film-school. Soon she is yelled at and approached by men of different ages, mainly from North African origin. One moment some guy brutally asks her if she wants to accompany him to his apartment, the next she’s called a “bitch” or a “slut”.

CLICK TO WATCH THE TRAILER:

Allegedly, this isn’t just a problem in Brussels. French feminist groups seized on the film to trigger debates on similar problems in France. And a May 2012 poll found that four in ten young women had been sexually harassed in London over the past year (according to The Guardian, August 3, 2012).

- “I WANT TO CHASE WOMEN, BUT I WANT MY WOMAN TO BE CHASTE…”

Of course sexism isn’t tied to any one culture. It should be clear that Sofie Peeters is not targeting Islam, for instance, or African men. Her film aims at unraveling the logic of male sexism, which can be found across cultures and in different types. My pupils, for instance, nod affirmatively when I present them with the names a flirty guy often gets on the one hand, and a flirty girl on the other: the former is sometimes rather positively called “playa”, while the latter is more easily referred to in degrading terms as “slut” or “whore”. Most of my pupils are not Muslim or African. Most of them are native, privileged Belgians, and they readily acknowledge that this kind of double-standard sexist speech exists in their social environment as well. It seems that more difficult social and economic circumstances only enhance this ever lurking presence of the male machismo. Michael Eric Dyson very clearly shows this while explaining the roots of men’s ambiguous treatment of women in hip-hop culture. Another book addressing the same issue, and well worth mentioning, is Tracy Denean Sharpley-Whiting’s Pimps Up, Ho’s Down – Hip Hop’s Hold on Young Black Women (New York University Press, 2007). Here are some thought-provoking quotes on the subject from Dyson’s book Holler If You Hear Me – Searching For Tupac Shakur (Plexus Publishing, London, 2001) – which balance a more positive assessment of hip-hop’s liberating potentials in this previous post.

Of course sexism isn’t tied to any one culture. It should be clear that Sofie Peeters is not targeting Islam, for instance, or African men. Her film aims at unraveling the logic of male sexism, which can be found across cultures and in different types. My pupils, for instance, nod affirmatively when I present them with the names a flirty guy often gets on the one hand, and a flirty girl on the other: the former is sometimes rather positively called “playa”, while the latter is more easily referred to in degrading terms as “slut” or “whore”. Most of my pupils are not Muslim or African. Most of them are native, privileged Belgians, and they readily acknowledge that this kind of double-standard sexist speech exists in their social environment as well. It seems that more difficult social and economic circumstances only enhance this ever lurking presence of the male machismo. Michael Eric Dyson very clearly shows this while explaining the roots of men’s ambiguous treatment of women in hip-hop culture. Another book addressing the same issue, and well worth mentioning, is Tracy Denean Sharpley-Whiting’s Pimps Up, Ho’s Down – Hip Hop’s Hold on Young Black Women (New York University Press, 2007). Here are some thought-provoking quotes on the subject from Dyson’s book Holler If You Hear Me – Searching For Tupac Shakur (Plexus Publishing, London, 2001) – which balance a more positive assessment of hip-hop’s liberating potentials in this previous post.

p. 184-185: If social empathy for young black males is largely absent in public opinion and public policies, the lack of understanding and compassion for the difficulties faced by poor young black females is even more deplorable. There exists within quarters of black life a range of justifications for black male behavior. Even if they are not wholly accepted by other blacks or by the larger culture, such justifications have a history and possess social resonance. Young black males hustle because they are poor. They become pimps and playas because the only role models they had are pimps and playas. Black males rob because they are hungry. They have babies because they seek to prove their masculinity in desultory paternity. They rap about violence because they came to maturity in enclaves of civic horror where violence is the norm. Black males do poorly in school because they are deprived of opportunity and ambition. Yet there are few comparable justifications for the black female’s beleaguered status.

p. 186: In its punishing hypocrisy, hip-hop at once deplores and craves the exuded, paraded sexuality of the “ho.” As it is with most masculine cultures, many of the males in hip-hop seek promiscuous sex while resenting the women with whom they share it. This variety of femiphobia turns on the stylish dishonesty that is transmuted into masculine wisdom: Never love or partner with the women you sleep with. Such logic imbues the male psyche with a toleration of split affinities that keep it from being fatally (as opposed to usefully) divided – the male can enjoy the very thing he despises, as long as it assumes its “proper” place. In order for “it” – promiscuous sex – to assume its proper place in male lives, women must assume their proper places. They must occupy their assigned roles with an eye to fulfilling their function as determined by men. If they are “hos,” they are to give unlimited, uncontested sex. If they are girlfriends or wives, they are to provide a stable domestic environment where sex is dutiful and proper. The entire arrangement is meant to maximize male sexual autonomy while limiting female sexuality, even if by dividing it into acceptable and unacceptable categories. The thought that a girlfriend or wife might be an ex-ho is a painful thought in such circles. The hip-hop credo can be summed up in this way: I want to chase women, but I want my woman to be chaste.

p. 186: In its punishing hypocrisy, hip-hop at once deplores and craves the exuded, paraded sexuality of the “ho.” As it is with most masculine cultures, many of the males in hip-hop seek promiscuous sex while resenting the women with whom they share it. This variety of femiphobia turns on the stylish dishonesty that is transmuted into masculine wisdom: Never love or partner with the women you sleep with. Such logic imbues the male psyche with a toleration of split affinities that keep it from being fatally (as opposed to usefully) divided – the male can enjoy the very thing he despises, as long as it assumes its “proper” place. In order for “it” – promiscuous sex – to assume its proper place in male lives, women must assume their proper places. They must occupy their assigned roles with an eye to fulfilling their function as determined by men. If they are “hos,” they are to give unlimited, uncontested sex. If they are girlfriends or wives, they are to provide a stable domestic environment where sex is dutiful and proper. The entire arrangement is meant to maximize male sexual autonomy while limiting female sexuality, even if by dividing it into acceptable and unacceptable categories. The thought that a girlfriend or wife might be an ex-ho is a painful thought in such circles. The hip-hop credo can be summed up in this way: I want to chase women, but I want my woman to be chaste.

p. 188-189: Human sexuality is a complex amalgam of competing interests that claim space in our evolving erotic identities. If human beings are to test the integrity and strength of their sexual identity, they must experiment with a variety of partners and circumstances to define their erotic temperament. At different points in life, different identities emerge, different priorities surface. […] If Tupac’s position – and by extension, hip-hop’s views – can be said to be hypocritical, it is because it reserved that prerogative exclusively for the male gender. When women exercise that prerogative, they are scathingly attacked. When men do so, they are seen as normal and healthy. What may be even more hypocritical – since many rappers claim to stand against white dominance – is hip-hop’s broad endorsement of conservative beliefs about female sexuality. When rappers express femiphobic stances, they often recycle stereotypes of poor black women promoted by right-wing hacks [becoming the “double” of their supposed enemies]: All they want is welfare, more babies, no work, and the freedom to party as they destroy the family and drive the men away.

Another feature of femiphobic culture is the simplistic division of women into angels and demons, both of which are problematic. If women are viewed as angels, the moment they depart from prescribed behavior they’re made into whores or bitches. If they are viewed as demons, it denies the complex sexual personae that all human beings express… Tupac’s femiphobia was certainly of this Manichean variety. “He definitely believed there were two kinds of women,” Jada Pinkett Smith says. “Which was a danger for Pac, because he had a way of putting you on a pedestal, and if there was one thing you did wrong, he would swear you were the devil.”

Another feature of femiphobic culture is the simplistic division of women into angels and demons, both of which are problematic. If women are viewed as angels, the moment they depart from prescribed behavior they’re made into whores or bitches. If they are viewed as demons, it denies the complex sexual personae that all human beings express… Tupac’s femiphobia was certainly of this Manichean variety. “He definitely believed there were two kinds of women,” Jada Pinkett Smith says. “Which was a danger for Pac, because he had a way of putting you on a pedestal, and if there was one thing you did wrong, he would swear you were the devil.”

The male psyche indeed often suspects there’s a demonic old witch lurking beneath the surface of angelic princesses and queens...

- SEXIST DEPICTIONS OF WOMEN – WOMEN AS “SCAPEGOATS”

Canadian author Jane Billinghurst assembled a “lusciously illustrated exploration of the temptress”, describing how this male and ambiguously valorized image of women has been ever present in human culture – through myth, historical accounts, film and art in general. Her book is aptly entitled Temptress (Greystone Books, Douglas & McIntyre Publishing Group, Vancouver/Toronto/Berkeley/New York, 2003). It gives a delightful overview of the contradictory meanings the image of the temptress is associated with, especially when adopted by women themselves.

First woman to come to the fore in Billinghurst’s book is Lilith, a female demon, a “monster woman”, mostly known because of the medieval Jewish text The Alphabet of Ben Sira, although her origins can be traced back to far more ancient times.

Here’s Billinghurst’s version of the Lilith story – p. 16-17:

Male painters of Victorian England were fascinated by the independent sexuality of Eve’s predecessor and Adam’s first wife, the mysterious Lilith. Created Adam’s equal, according to medieval Jewish folklore, Lilith was appalled when her husband insisted on the missionary position for sex. She knew she had been made from the same clay that he had, and she wanted an equal say in how their love life unfolded. She wanted to experiment with this new flesh, to explore the range of pleasures it could provide.

Male painters of Victorian England were fascinated by the independent sexuality of Eve’s predecessor and Adam’s first wife, the mysterious Lilith. Created Adam’s equal, according to medieval Jewish folklore, Lilith was appalled when her husband insisted on the missionary position for sex. She knew she had been made from the same clay that he had, and she wanted an equal say in how their love life unfolded. She wanted to experiment with this new flesh, to explore the range of pleasures it could provide.

Adam, in contrast, was rather prude. The idea of creating a sexual dialogue, of reacting to the signs fed back to his body from Lilith’s, of following an impulse not knowing where it might lead, was foreign to him. He did not yet know enough about his own urges to feel comfortable abandoning himself to Lilith’s. He refused to listen to his wife, and Lilith submitted to night after night of missionary sex – her mind, no doubt, on other things, like the wide expanse of the night sky, the rustling of creatures in the bushes… and the possibilities of life without Adam.

Resentment built in Lilith until she could stand it no longer. Undaunted by the fact that she knew nothing about the world outside paradise, according to the text of The Alphabet of Ben Sira, she “uttered the ineffable name of God,” the gates of Eden swung open, and off she went to make her own way in the world, unencumbered by her sexually unimaginative husband.

Lilith’s life from then on has been portrayed as one long party. She went to the Red Sea, where she cavorted with all manner of hideous demons, indulging in whatever sexual positions she wanted and producing hundreds of demon children. When Adam complained to God that his supposed helpmeet had left him, God sent three angels to bring Lilith back to where she belonged. But she refused to return: she had found a place where she could indulge her sexuality, and she had no regrets.

Despite her new lifestyle, Lilith never completely severed her ties with the uptight male to whom she had once been married. After Adam lost his immortality and begat humankind, Lilith started taking the lives of young children, creeping in at night through open windows and snatching their breath away. When unsuspecting parents tried to wake their offspring, they found that their previously healthy babies had died in the night. The three angels were horrified by such heartless, vindictive behavior. They could not force Lilith to return to Eden, but they did strike a bargain with her. Her window of opportunity for such malicious behavior was restricted to eight days after birth for baby boys and twenty days for baby girls. In addition, if amulets were hung inscribed with the angel’s names – Senoy, Sansenoy, and Semangelof – Lilith agreed to stay away.

Despite her new lifestyle, Lilith never completely severed her ties with the uptight male to whom she had once been married. After Adam lost his immortality and begat humankind, Lilith started taking the lives of young children, creeping in at night through open windows and snatching their breath away. When unsuspecting parents tried to wake their offspring, they found that their previously healthy babies had died in the night. The three angels were horrified by such heartless, vindictive behavior. They could not force Lilith to return to Eden, but they did strike a bargain with her. Her window of opportunity for such malicious behavior was restricted to eight days after birth for baby boys and twenty days for baby girls. In addition, if amulets were hung inscribed with the angel’s names – Senoy, Sansenoy, and Semangelof – Lilith agreed to stay away.

Strangling babies while they slept was not Lilith’s only revenge against the man who had denied her pleasure. She also wafted into the dreams of men who slept alone. A slight rub of skin on skin or skin on sheet, and the men could not help but react physically to the thoughts she conjured up. The wet dream was her gift to the sons of Adam. A slight morning stickiness, proof of the nocturnal emission, was often the only sign of her visit – and a yearning to remember just what pleasure it was that she had promised as she passed by.

Lilith lingers in the thoughts of men as a reminder of sexual opportunities lost or not yet found. Here was a woman who was not afraid to take charge, who could imagine delights of which Adam could not conceive. To abandon oneself to the charms of such a woman – who knows where that might lead? Men have been wondering ever since.

Although this story could be interpreted as a story about an emancipated woman in some contexts – as Billinghurst suggests at the end of her account –, it should first be considered as a typically male and actually sexist depiction of female sexuality. Moreover, the question remains how women can truly emancipate themselves from male imagination if they simply imitate the images they’re presented with, while arguing – in a spirit of rivalry between the sexes – that they have every right to claim those images as their own. For the time being, I let this question to be answered by the pop diva’s of this world, like Madonna. Let’s take a closer look at how female sexuality and the relationship between the sexes is portrayed in the story of Lilith:

- A woman who desires sexual freedom and who wants to have a say in her own destiny transgresses a sacred order of things, disrespecting important taboos that try to avoid chaos in human life. Lilith “uttered the ineffable name of God…”

- A woman who desires sexual freedom and who wants to have a say in her own destiny is responsible for all kinds of evil in the world and the loss of what could be “paradise”. How could such a woman be a good mother to her children? She’s a deadly disruption of family life, as she is unable to provide a sustainable environment for children. Undaunted by the fact that she knew nothing about the world outside paradise, Lilith uttered the ineffable name of God, the gates of Eden swung open, and off she went to make her own way in the world… After Adam lost his immortality and begat humankind, Lilith started taking the lives of young children, creeping in at night through open windows and snatching their breath away. When unsuspecting parents tried to wake their offspring, they found that their previously healthy babies had died in the night…

- Men are merely helpless victims of a woman who desires sexual freedom and who wants to have a say in her own destiny. Unfortunately, men cannot always be on guard against the seductive powers of the demonic woman. The wet dream was Lilith’s gift to the sons of Adam. A slight morning stickiness, proof of the nocturnal emission, was often the only sign of her visit…

A main challenge for humankind has always been how to restore “paradise” in times of crisis. As the story of Lilith and many other myths make clear, sexuality – especially from the female side – has always been experienced as one of the main sources of turmoil. That’s why sexuality is regulated culturally. It’s often considered taboo because of the possible destructive outcomes it’s associated with. On the other hand, however, fertile sexuality is also needed to secure the survival and stability of communities. Ritualistic “arrangements” – from (temple) prostitution to the institution of marriage – try to give sexuality a proper place in society, so it can be experienced in its beneficial aspects.

A main challenge for humankind has always been how to restore “paradise” in times of crisis. As the story of Lilith and many other myths make clear, sexuality – especially from the female side – has always been experienced as one of the main sources of turmoil. That’s why sexuality is regulated culturally. It’s often considered taboo because of the possible destructive outcomes it’s associated with. On the other hand, however, fertile sexuality is also needed to secure the survival and stability of communities. Ritualistic “arrangements” – from (temple) prostitution to the institution of marriage – try to give sexuality a proper place in society, so it can be experienced in its beneficial aspects.

No wonder then that certain individuals, who don’t seem to respect a community’s peculiar cultural arrangement of taboos and rituals, are often perceived as provocative and dangerous. They are easily sacrificed, allegedly in order to protect the community from more or imminent chaos. The social mind (male as well as female) actually always suspects sexually independent women who don’t seem to care about our long and diverse traditions of patriarchal taboos and rituals.

Sexually independent women are fascinating and threatening at the same time, revered and loathed, loved and hated. They are mysterious, seemingly beyond any control, evoking the numinous experience of the sacred – Rudolf Otto (1869-1937) speaks of “the holy”. Other women jealously admire them, while men desire them, resenting the destructive power they seem to posses. As Michael Eric Dyson pointed out, hip-hop culture is one clear example where these dynamics come to the fore. Desired and despised “hos” or “whores” are often the first to fall victim to the hidden fears of men and women whose sense of identity feels threatened.

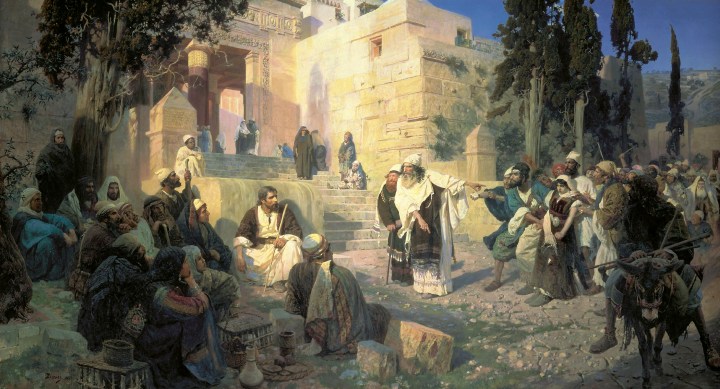

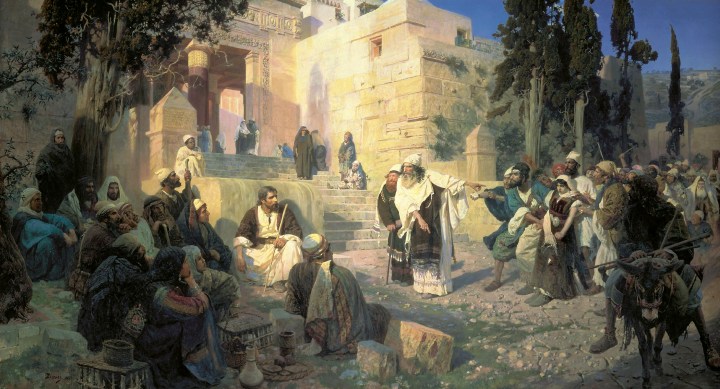

The image of sexually independent, “adulterous” women who are sacrificed – mostly stoned to death – in order to “cleanse” a community, is, however sadly, deeply embedded in our social consciousness. Adulterous men are spared because they are perceived as poor victims of “evil” and “dangerous” temptresses. Men are said not to be responsible for their own words or actions towards sexually independent women. They justify themselves by making these women entirely responsible for what happens to them, saying that these women “provoked” them. The case of Sarah Tobias, who was gang raped, is but one well-known example where this kind of sick reasoning was applied. Her story provided the subject for The Accused, a 1988 Jonathan Kaplan movie with an Oscar winning Jodie Foster portraying Tobias. The men who raped Sarah Tobias tried to defend themselves by insinuating that they fell victim to the seductive and promiscuous attitude of the woman. The reaction of Sharia4Belgium against Sofie Peeters’ Femme de la Rue is analogous. According to this group of Muslims, Peeters was sexually harassed because she “provoked” men by “dressing like a whore”.

The image of sexually independent, “adulterous” women who are sacrificed – mostly stoned to death – in order to “cleanse” a community, is, however sadly, deeply embedded in our social consciousness. Adulterous men are spared because they are perceived as poor victims of “evil” and “dangerous” temptresses. Men are said not to be responsible for their own words or actions towards sexually independent women. They justify themselves by making these women entirely responsible for what happens to them, saying that these women “provoked” them. The case of Sarah Tobias, who was gang raped, is but one well-known example where this kind of sick reasoning was applied. Her story provided the subject for The Accused, a 1988 Jonathan Kaplan movie with an Oscar winning Jodie Foster portraying Tobias. The men who raped Sarah Tobias tried to defend themselves by insinuating that they fell victim to the seductive and promiscuous attitude of the woman. The reaction of Sharia4Belgium against Sofie Peeters’ Femme de la Rue is analogous. According to this group of Muslims, Peeters was sexually harassed because she “provoked” men by “dressing like a whore”.

Poor, helpless men! Whether men abuse the name of God as an addition in the justification of their own (verbal or physical) violence or not, the bottom line remains: the harassed, raped or stoned victim is a scapegoat – held responsible for the violence she has to endure and accused of the turmoil men experience in their desires, while in fact being innocent. Let’s face it: are men really that weak that they cannot master their own desires, words or actions? And let’s face something else: who’s the real victim, the – seemingly – sexually independent and dangerously powerful seductive woman who’s stoned to death, or the men who stone her? Is she able to defend herself against those so-called “weak”, but nevertheless so-called “heroic” men? Being stoned is passive. To stone is active. For once our language doesn’t lie in presenting the natural order of things.

Poor, helpless men! Whether men abuse the name of God as an addition in the justification of their own (verbal or physical) violence or not, the bottom line remains: the harassed, raped or stoned victim is a scapegoat – held responsible for the violence she has to endure and accused of the turmoil men experience in their desires, while in fact being innocent. Let’s face it: are men really that weak that they cannot master their own desires, words or actions? And let’s face something else: who’s the real victim, the – seemingly – sexually independent and dangerously powerful seductive woman who’s stoned to death, or the men who stone her? Is she able to defend herself against those so-called “weak”, but nevertheless so-called “heroic” men? Being stoned is passive. To stone is active. For once our language doesn’t lie in presenting the natural order of things.

- AN EXPLANATION OF SEXISM FROM THE POINT OF VIEW OF MIMETIC THEORY

In order to explain a variety of religious and cultural phenomena and the often contradictory things they’re associated with, René Girard proposes to look for the way these phenomena can be traced back to violent situations and the attempts to cope with this violence. So, to understand the different cultural interpretations of sexuality, and female sexuality in particular – in its demonic as well as in its divine “sacred” aspects –, we should ask ourselves: what could be the basic connection between heterosexuality – since this is what interests us at the moment – and violence? The answer from Girard’s so-called “mimetic theory” is quite obvious: women are often objects of “mimetic desire”, and this desire leads to “mimetic rivalry” or violence.

Mimetic or imitative desire emerges when two or more individuals more or less unwittingly take each other as a model for their own desire. Imitating someone else in desiring a certain object always complicates my relationship with the other. Taking the other as a model for my desire also means that he becomes an obstacle in the pursuit for the object we simultaneously desire. In this way the other appears as someone I admire (whereby I take him as a model), while at the same time he appears as someone I envy (as he becomes an obstacle who tries to posses what I consider rightfully mine). The other, in short, becomes my partner in a mutual love/hate relationship. Since he possesses a similar capacity for imitation, the other will in turn take me as a model, thereby reinforcing his own desire. This process makes me, again, an obstacle for him – his “double” – and this dynamic indeed all too often ends up in an inextricable “mimetic rivalry” (a rivalry based on imitation). And indeed: a classic, archetypal example of this kind of competition is the rivalry between two (or more) men desiring the same woman.

Mimetic or imitative desire emerges when two or more individuals more or less unwittingly take each other as a model for their own desire. Imitating someone else in desiring a certain object always complicates my relationship with the other. Taking the other as a model for my desire also means that he becomes an obstacle in the pursuit for the object we simultaneously desire. In this way the other appears as someone I admire (whereby I take him as a model), while at the same time he appears as someone I envy (as he becomes an obstacle who tries to posses what I consider rightfully mine). The other, in short, becomes my partner in a mutual love/hate relationship. Since he possesses a similar capacity for imitation, the other will in turn take me as a model, thereby reinforcing his own desire. This process makes me, again, an obstacle for him – his “double” – and this dynamic indeed all too often ends up in an inextricable “mimetic rivalry” (a rivalry based on imitation). And indeed: a classic, archetypal example of this kind of competition is the rivalry between two (or more) men desiring the same woman.

Mimetic rivals remain blind for their interdependency. They are both convinced of the “originality” of their own desire and perceive the other as wrongfully laying claim to something that’s not his or hers. In the end it’s not about obtaining certain objects anymore, but about obtaining a kind of prestige, image or status. More specifically, both rivals desire the other to acknowledge them as autonomously desiring individuals. However, the more they desire to convince themselves and the other of their own glamorous autonomy, the more this desire is mutually imitated and the more this autonomy remains an object(ive) that is not obtained – and so remains desired. Mimesis or imitation stays the hidden source of a tragic competition wherein rivals more and more become each other’s equals as they try to distinguish themselves from each other. Mimesis stays the hidden source of an ever increasing desire for “uniqueness” and “independency”, and an ever increasing failure of reaching these goals.

So what did ancient men do, men who had to fear the competition and violence of fellow men – a violence which could destroy the stability and eventual survival of their community? What did they do to enforce and secure their own status and prestige? Well, apparently they set up different systems of taboos, rituals, plays and games to prevent mimetic competitive tendencies from becoming destructive to community life. But in coping with violence associated with heterosexuality, men failed to take into account their own share and responsibility in that violence, unable to fully acknowledge the mimetic nature of their desires. Instead, women had to take responsibility for the behavior of men: in one culture they had to wear a veil in public “to protect the honor of their husband”, while in another they had to act as mesmerizing and beautiful temptresses – trophies to show off a man’s success and status. Female sexuality was regulated to fulfill men’s expectations and to keep them from fighting each other: prostitutes were considered no one man and every man’s possession – often hailed, in the case of temple prostitution, as allowing the potentially violent nature of “sacred” sexuality in a beneficiary way, while in other cultural contexts also despised as a kind of “necessary evil”.

So what did ancient men do, men who had to fear the competition and violence of fellow men – a violence which could destroy the stability and eventual survival of their community? What did they do to enforce and secure their own status and prestige? Well, apparently they set up different systems of taboos, rituals, plays and games to prevent mimetic competitive tendencies from becoming destructive to community life. But in coping with violence associated with heterosexuality, men failed to take into account their own share and responsibility in that violence, unable to fully acknowledge the mimetic nature of their desires. Instead, women had to take responsibility for the behavior of men: in one culture they had to wear a veil in public “to protect the honor of their husband”, while in another they had to act as mesmerizing and beautiful temptresses – trophies to show off a man’s success and status. Female sexuality was regulated to fulfill men’s expectations and to keep them from fighting each other: prostitutes were considered no one man and every man’s possession – often hailed, in the case of temple prostitution, as allowing the potentially violent nature of “sacred” sexuality in a beneficiary way, while in other cultural contexts also despised as a kind of “necessary evil”.

But enough with this past tense! If one thing becomes clear from the above mentioned examples of certain tendencies in today’s hip-hop culture, Sofie Peeters’ Femme de la Rue, the “gang rape” case of Sarah Tobias, and Sharia4Belgium’s reaction against Peeters, it’s this: we, men, still very often fail to realize how we turn women into scapegoats – victims accused of things they’re not (or certainly not fully – where’s the adulterous husband while adulterous women are stoned to death?) responsible for.

Girard’s mimetic theory explains how sexist tendencies originate in men’s inability to locate the real source of instability and violence in the context of heterosexuality. Instead of acknowledging that anger and rivalry emerge because of the mimetic nature of their desire, men mistakenly locate the source of their anger and rivalry in the object of their desire: the woman. She thus has to pay the price to fulfill men’s lust for status, honor, power and prestige. From the sexist point of view, women are to be respected if they “honor” men’s status, and only then! A sexist man’s love for status is worth more to him than the love for the well-being and happiness of his closest “other” and neighbor – his wife. That’s why a sexist man can be called idolatrous: kneeling to the “divine” image he has created of himself, while failing to love the “other” who does not necessarily answer his needs (which precisely makes the other “other”).

- WOMEN, JESUS AND ROCK ‘N’ ROLL

In my book Vrouwen, Jezus en rock-‘n-roll (Altiora Averbode, 2009) – “Women, Jesus and rock ‘n’ roll” –, I suggested a feminist reading of the story of the Fall in Genesis. Like Pandora in Greek mythology, Eve is portrayed as being mainly responsible for the evils humankind has to suffer. So the sexist element is clearly present in the Hebrew Bible as well. No doubt about that. It’s no wonder that Michelangelo (1475-1564) even depicted the seductive and “dangerous” serpent as a woman in his paintings at the Sistine Chappell. Eve is an “Eve of destruction”.

A more contextual reading, however, delivers different results. In short, Eve is not condemned because she is a woman, but because she is unable to resist a destructive kind of envy (or, more generally, “mimetic desire”). Consider this analogy with a story a few chapters further on in the book of Genesis: Cain is not condemned because he is the oldest of two sons, but because he is unable to resist a destructive kind of jealousy – he kills his brother Abel.

So amidst sexist tendencies there are also texts in the Bible which criticize the mechanisms that turn women into scapegoats. I tried to make this clear in a further contextual reading of the Song of Songs, taking the story of Jesus’ forgiveness of an adulterous woman in John 8:1-11 and his consideration of prostitutes in Matthew 21:28-32 as interpretive keys. But it would go too far to explain this here. Suffice to say that some important biblical texts are surprisingly subversive – “rock ‘n’ roll” indeed – towards the mechanisms that turn women into scapegoats.

This is in line with Girard’s claim that the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament gradually attack the core of scapegoat mechanisms as the cornerstones of human relationships. Christ, in entering that core by offering to become the forgiving substitute victim of all scapegoats, transforms human relationships from within in a way that no other human being seems to have done. But to grasp this more fully I advise the reader to delve into the work of James Alison.

Anyway, Christ – as others have done – challenges us to build our relationships on “love for our neighbor” instead of on “love for our status or our prestige”. So if a woman wears a veil, the question should not be whether and on what grounds she is obligated to wear a veil. The question should be what motivates her to wear a veil: is it fear of losing her status in the eyes of her husband and other men if she doesn’t, or is it a freely chosen way of expressing the unique type of love she feels for her husband? In the latter case, she won’t be offended or feel threatened if other women don’t follow her example. Because she has freely chosen to wear a veil, she will not be jealous or resentful towards women without a veil. If, on the other hand, she chooses to wear a veil out of fear, she might develop resentment towards women who seem to “get away” with not wearing a veil. The only thing she can do then is to convince herself that her masochistic and “heroic” self-sacrifice is a way to attain a “sacred” (or “holy”) status – which is a way of self-glorification by submitting to a supposedly admirable (self-) image or idol. This kind of perverse, masochistic and often violent martyrdom is all too familiar. Which brings me to the heart of modern fundamentalism and its continuation of sexist tendencies.

Anyway, Christ – as others have done – challenges us to build our relationships on “love for our neighbor” instead of on “love for our status or our prestige”. So if a woman wears a veil, the question should not be whether and on what grounds she is obligated to wear a veil. The question should be what motivates her to wear a veil: is it fear of losing her status in the eyes of her husband and other men if she doesn’t, or is it a freely chosen way of expressing the unique type of love she feels for her husband? In the latter case, she won’t be offended or feel threatened if other women don’t follow her example. Because she has freely chosen to wear a veil, she will not be jealous or resentful towards women without a veil. If, on the other hand, she chooses to wear a veil out of fear, she might develop resentment towards women who seem to “get away” with not wearing a veil. The only thing she can do then is to convince herself that her masochistic and “heroic” self-sacrifice is a way to attain a “sacred” (or “holy”) status – which is a way of self-glorification by submitting to a supposedly admirable (self-) image or idol. This kind of perverse, masochistic and often violent martyrdom is all too familiar. Which brings me to the heart of modern fundamentalism and its continuation of sexist tendencies.

- “CHECK FOR TREACHEROUS WOMEN” WITHIN AND OUTSIDE FUNDAMENTALISM

In his book, Religion Explained – The Evolutionary Origins of Religious Thought (Basic Books, New York, 2001), French anthropologist Pascal Boyer explains how fundamentalist religious communities have the tendency to “check for cheaters or defectors” as a means to (re)structure themselves and strengthen their coalitions. The public and “spectacular” punishment of defectors – i.e. individuals who are perceived as being not loyal or a threat to a community’s traditionally informed identity –, is a powerful signal to discourage further infidelity, especially in times of crisis.

In his book, Religion Explained – The Evolutionary Origins of Religious Thought (Basic Books, New York, 2001), French anthropologist Pascal Boyer explains how fundamentalist religious communities have the tendency to “check for cheaters or defectors” as a means to (re)structure themselves and strengthen their coalitions. The public and “spectacular” punishment of defectors – i.e. individuals who are perceived as being not loyal or a threat to a community’s traditionally informed identity –, is a powerful signal to discourage further infidelity, especially in times of crisis.

Guomundur Ingi Markusson pointed out some very interesting connections between Boyer’s evolutionary psychology and René Girard’s mimetic theory in an article for Contagion (number 11; Violent Memes and Suspicious Minds: Girard’s Scapegoat Mechanism in the Light of Evolution and Memetics). Markusson rightly quotes the following passage from Boyer’s Religion Explained, wherein Boyer explains how fundamentalism originated as a modern religious phenomenon (more specifically as an attempt to “restructure traditional coalitions” in the face of secular society’s indifference towards religious demands that are considered necessary) – p. 294:

The message from the modern world is not just that other ways of living are possible, that some people may not believe, or believe differently, or feel unconstrained by religious morality, or (in the case of women) make their own decisions without male supervision. The message is also that people can do that without paying a heavy price. Nonbelievers or believers in another faith are not ostracized; those who break free of religious morality, as long as they abide by the laws, still have a normal social position; and women who dispense with male chaperons do not visibly suffer as a consequence. This “message” may seem so obvious to us that we fail to realize how seriously it threatens social interaction that is based on coalitional thinking. Seen from the point of view of a religious coalition, the fact that many choices can be made in modern conditions without paying a heavy price means that defection is not costly and is therefore very likely.

So, also in the case of modern fundamentalism, independent women not only pose a challenge to male dominance, authority and self-esteem, but also to the very basis of community life and cultural identity. That’s why the fundamentalist reflex consists in treating sexually independent women as “whores”. They are allowed to carry out a relative independency only if they are willing to pay the price of being “public property” – belonging to no one man and to all men. Because of their outspoken indifference towards cultural taboos and ritualistic arrangements (such as marriage), these women are “defectors”. They are perceived as suspicious threats to “the normal state of affairs”, and shouldn’t go totally “unpunished”. They could receive some form of respect if they played along with male expectations, but, as I mentioned earlier, they are easily victimized in times of crisis. Even if they have nothing to do with the crisis itself. In this sense we could compare these women with ancient Greek pharmakoi – scapegoat victims that were sacrificed in times of social turmoil or ecological disasters.

A famous example of a (seemingly) sexually independent and seductive woman who was sacrificed in uncertain times is Dutch-born beauty Mata Hari (1876-1917), an exotic dancer. I’d like to end this post by citing the story of her untimely death, as Jane Billinghurst describes it in the aforementioned book Temptress. Mata Hari wanted to work as a spy for the French during the First World War. Unfortunately for her, things got out of hand. It should be clear, from these and other already mentioned cases, that sexism is not a unique characteristic of a certain type of Islam, or of certain passages in the Bible, or of certain tendencies in African (American) culture, or of white male conservatives. It’s a cross-cultural, all too present reality with a long history in many (often contradictory) guises. Here’s the quote from Billinghurst’s book – p. 88-91:

Mata Hari [eager to earn her reward from the French, working as a spy] set her sights on the conquest of the German envoy in Madrid, Major Arnold von Kalle. The investigative work that led her to him was simple: she looked up his name in the phone book, requested an appointment, and set to work. She coyly described her technique: “I did what a woman does in such circumstances where she wants to make a conquest of a gentleman, and I soon realized that von Kalle was mine.”

Mata Hari [eager to earn her reward from the French, working as a spy] set her sights on the conquest of the German envoy in Madrid, Major Arnold von Kalle. The investigative work that led her to him was simple: she looked up his name in the phone book, requested an appointment, and set to work. She coyly described her technique: “I did what a woman does in such circumstances where she wants to make a conquest of a gentleman, and I soon realized that von Kalle was mine.”

Unfortunately for Mata Hari, von Kalle suspected her motives and decided to send messages to Germany about her in a code he knew the Allies had broken. If she was working for the French, these messages would make them believe she was working for him as well. The ploy worked. The French, anxious to crack down on spies to boost morale in their ravaged country, hauled Mata Hari in. The dancer-cum-courtesan-cum-amateur spy could not believe it. She protested vehemently that the only spying she had done had been for France. The French authorities needed a scapegoat, however, and Mata Hari fit the bill perfectly.

Sexy and unnervingly independent, she was definitely the kind of woman it was dangerous to have around. The stage had proved to be a place of liberation for many women in the early twentieth century, but when the war came, actresses and dancers, who often supplemented their incomes as mistresses and courtesans, were looked down on as subversive forces likely to upset the order of the world. Women feted for their performances when all was right with the world were now highly suspect. They not only ignored the rules but were privy to the most intimate thoughts and most unguarded moments of powerful men. If they slept with men for money, these self-centered, subversive creatures were also likely to sleep with them for secrets. The more erotic the woman, the more havoc she could wreak. And Mata Hari, a woman to whom borders meant nothing, was eroticism personified. She had to be stopped.

On 13 February 1917, Mata Hari was arrested on charges of espionage and taken to the Saint-Lazare prison for women. When Mata Hari had choreographed her dance performances, she had skillfully woven into her persona hints of temptresses past, such as the forbidden Oriental delights of Cleopatra. When times were good, such associations had served to heighten her appeal, but in the atmosphere of suspicion and intrigue of the war, associations with the exotic “other” now conjured up images of treachery rather than pleasure. Mata Hari’s dark complexion, which previously had intrigued, now disgusted. Given the kind of woman she was, Lieutenant André Mornet, the prosecuting attorney for the Third Council of War in France, explained why she had to be guilty:

“The Zelle lady appeared to us as one of those international women – the word is her own – who have become so dangerous since the hostilities. The ease with which she expresses herself in several languages, especially French, her numerous relations, her subtle ways, her aplomb, her remarkable intelligence, her immortality, congenital or acquired, all contributed to make her a suspect.”

The media quickly made the connection between Mata Hari and the images of evil women that had been hanging in galleries and fleshed out in literature over the past fifty years just waiting for a moment such as this. She was described as “a sinister Salome, who played with the heads of our soldiers in front of the German Herod.” She was compared to Delilah, another expert in getting men to spill deadly secrets. Her frank sexuality was cited as proof of her capacity for betrayal.

The media quickly made the connection between Mata Hari and the images of evil women that had been hanging in galleries and fleshed out in literature over the past fifty years just waiting for a moment such as this. She was described as “a sinister Salome, who played with the heads of our soldiers in front of the German Herod.” She was compared to Delilah, another expert in getting men to spill deadly secrets. Her frank sexuality was cited as proof of her capacity for betrayal.

Gustave Steinhauer, a German spymaster, wrote that women became spies because of their lust for excitement Whereas the male spy worked for the good of his country, the female spy was focused on self-gratification. And because of their inherently treacherous natures, women who turned to espionage were “far more cunning, far more adroit… than the most accomplished masculine spy.” A novel based on Mata Hari’s story emphasizes the intense personal satisfaction a woman derives from betrayal when the central character exclaims: “How I would fasten my mouth against their hearts! And I would suck them – I would suck them until there wasn’t a drop of blood left, tossing away their empty carcasses.” Appalled, those responsible for keeping order in times of mass destruction closed ranks against the independent international woman and had her shot.

Mata Hari was a sexual adventuress who had the temerity to assert herself in areas of male privilege. She herself had sketched the details that would ensure her destruction. She had portrayed herself as a woman without borders, a woman with an exotic past who reveled in the delights of sex. As long as peace reigned in Europe, such a woman drew crowds anxious to experience a vicarious thrill. When war broke out, however, men knew from all they had read and heard that a woman of Mata Hari’s type was deadly.

The French prosecutors in Mata Hari’s case rushed through the formalities to ensure that justice was done. The jury was swept along on the coattails of their conviction, even though, as the prosecutors later admitted, there was not enough evidence against Mata Hari “to whip a cat.” The temptress mantle she had draped so coquettishly around her shoulders proved to be too effective a costume. The French firing squad believed it was doing its God-given duty when it reduced this vital and proud woman, who had brought so much pleasure to so many men, to nothing more than a “crumpled heap of petticoats,” stripped of all their menacing power.

The storytellers warn that when men are enraptured by women such as Salome and Delilah, they make wild promises and whisper secrets that contain the seeds of their undoing. Subversive temptresses of this ilk are so firmly entrenched in the collective male imagination that the image is easily transferred to real-life women who may – or may not – harbor the destructive, chaotic tendencies men are so quick to ascribe to them. An unfortunate few, like Mata Hari, find that the wave of male desires that sweeps them to success when the future looks bright turns into an undertow of male suspicion that drags them down when the tide turns.

The storytellers warn that when men are enraptured by women such as Salome and Delilah, they make wild promises and whisper secrets that contain the seeds of their undoing. Subversive temptresses of this ilk are so firmly entrenched in the collective male imagination that the image is easily transferred to real-life women who may – or may not – harbor the destructive, chaotic tendencies men are so quick to ascribe to them. An unfortunate few, like Mata Hari, find that the wave of male desires that sweeps them to success when the future looks bright turns into an undertow of male suspicion that drags them down when the tide turns.

Last week, one of my pupils said something what countless others already said before him, and what countless others will repeat after him – it’s a cultural thing foremost, in our so-called secularized Belgian society:

Last week, one of my pupils said something what countless others already said before him, and what countless others will repeat after him – it’s a cultural thing foremost, in our so-called secularized Belgian society: “For whoever wants to save their life will lose it… What good is it for someone to gain the whole world, and yet lose or forfeit their very self?” (Luke 9:24a-25).

“For whoever wants to save their life will lose it… What good is it for someone to gain the whole world, and yet lose or forfeit their very self?” (Luke 9:24a-25). Another example: scientific rationality might explain how the universe came into being, but we need philosophical rationality to deal with the question whether or not there is an ultimate purpose of “all that is”, whether or not there will be some “perfection” of the universe. Scientifically speaking, there is none, but it’s logically very debatable that the scientific answer is the only meaningful or true answer to this question. The belief that only scientific claims are true or meaningful is known as scientism, which is problematic. From The Skeptic’s Dictionary: “Scientism, in the strong sense, is the self-annihilating view that only scientific claims are meaningful, which is not a scientific claim and hence, if true, not meaningful. Thus, scientism is either false or meaningless.”

Another example: scientific rationality might explain how the universe came into being, but we need philosophical rationality to deal with the question whether or not there is an ultimate purpose of “all that is”, whether or not there will be some “perfection” of the universe. Scientifically speaking, there is none, but it’s logically very debatable that the scientific answer is the only meaningful or true answer to this question. The belief that only scientific claims are true or meaningful is known as scientism, which is problematic. From The Skeptic’s Dictionary: “Scientism, in the strong sense, is the self-annihilating view that only scientific claims are meaningful, which is not a scientific claim and hence, if true, not meaningful. Thus, scientism is either false or meaningless.” It is no coincidence that, from a Christian point of view, there are prayers like the one ascribed to Saint Francis of Assisi, containing the words:

It is no coincidence that, from a Christian point of view, there are prayers like the one ascribed to Saint Francis of Assisi, containing the words: In the words of the great and late Christian writer, G.K. Chesterton (1874-1936), the situation of student A can be characterized as follows:

In the words of the great and late Christian writer, G.K. Chesterton (1874-1936), the situation of student A can be characterized as follows: False prophets or false messiahs (in religion, politics, health care, etc.) are people who try to tell us what we need to get to paradise (a nice house, a good career, a healthy body, a safe but entertaining life etc.), and also scare us with the evil dangers that could send us to hell. They are doctors who constantly produce the disease they supposedly liberate us from. But, of course, they never really liberate us, for they are dependent on the disease to be able to manifest themselves as “liberators” or “messiahs”. They produce one self-fulfilling prophecy after the other. For instance, the more a gun lobby convinces us that we should protect ourselves with weapons to keep safe in an “evil, ugly world”, the more people will get killed because of gun fire, the more we will feel unsafe, the more the gun lobby will be able to convince us of “the unsafe world”, the more we buy guns, etc.

False prophets or false messiahs (in religion, politics, health care, etc.) are people who try to tell us what we need to get to paradise (a nice house, a good career, a healthy body, a safe but entertaining life etc.), and also scare us with the evil dangers that could send us to hell. They are doctors who constantly produce the disease they supposedly liberate us from. But, of course, they never really liberate us, for they are dependent on the disease to be able to manifest themselves as “liberators” or “messiahs”. They produce one self-fulfilling prophecy after the other. For instance, the more a gun lobby convinces us that we should protect ourselves with weapons to keep safe in an “evil, ugly world”, the more people will get killed because of gun fire, the more we will feel unsafe, the more the gun lobby will be able to convince us of “the unsafe world”, the more we buy guns, etc. One Sabbath Jesus was going through the grainfields, and as his disciples walked along, they began to pick some heads of grain. The Pharisees said to him, “Look, why are they doing what is unlawful on the Sabbath?”

One Sabbath Jesus was going through the grainfields, and as his disciples walked along, they began to pick some heads of grain. The Pharisees said to him, “Look, why are they doing what is unlawful on the Sabbath?”