René Girard devotes six chapters to A Midsummer Night’s Dream in A Theater of Envy, his book on William Shakespeare (for references I use the edition of St. Augustine’s Press, South Bend, Indiana, 2004 – originally this title was edited by Oxford University Press, 1991). I’ve tried to rework some of Girard’s insights by using the diagrams I’ve developed (for more information, click here for “Types of the Scapegoat Mechanism”). But first things first: a plot summary.

1. PLOT OF A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, one of Shakespeare’s most beloved comedies, portrays some strange events surrounding the wedding of Theseus, Duke of Athens, and Hippolyta, queen of the Amazons. The play consists of three plots, interconnected by the noble marriage.

First there is the story of four young Athenian lovers who are invited to the celebration. Fair Hermia is in love with Lysander and refuses to submit to her father Egeus’ demand that she wed Demetrius. Meanwhile, her childhood friend Helena desperately falls for Demetrius. Hermia and Lysander escape to an enchanted forest outside Athens. Informed by the still desperate Helena, Demetrius follows them in hopes of killing Lysander. Helena chases Demetrius, promising to love him more than Hermia, but he rejects her offer with cruel insults.

Oberon, king of the fairies and at that time in an envious quarrel over a changeling with his wife and queen Titania, observes the cruelty of Demetrius. This second plot about the fairies intervenes with the first one when Oberon asks his servant, Robin “Puck” Goodfellow, to apply a magical juice to the eyelids of the sleeping Demetrius. The juice is derived from a flower called “love-in-idleness” and causes awakening persons to fall in love with the first creature they see. Oberon hopes to let Demetrius fall in love with Helena. However, Puck mistakes Lysander for Demetrius and Lysander falls in love with Helena. Oberon is able to correct Puck’s mistake and uses the magic to let Demetrius fall in love with Helena as well. Rivaling Lysander and Demetrius then end up seeking a place to duel each other, leaving Hermia enraged and desperate as she accuses Helena of stealing Lysander away from her. Puck, following Oberon’s orders, prevents the duel from happening and removes the charm from Lysander. Lysander returns to loving Hermia, while Demetrius now loves Helena.

The four young lovers return to Athens to witness the celebration of Theseus’ wedding. A group of six amateur actors performs “Pyramus and Thisbe”. These six craftsmen (among them a guy named Bottom who is eager to play nearly every role) prepared themselves in the enchanted forest and went through some upheaval as well. Like the tale of the four lovers, this third plot again is connected to the world of the fairies by Puck’s magical love potion. Oberon lets his wife fall in love with Bottom so he can blackmail her and claim her changeling. He succeeds and after removing the spell from his wife he goes to Athens with her to bless the house of Theseus. All’s well that ends well, so it seems…

2. MIMETIC INTERPLAYS IN THE TALE OF THE FOUR LOVERS

I will focus on the subplot of the four young Athenian lovers. René Girard, in the aforementioned book A Theater of Envy, interprets the love shenanigans during the fairy night as consequences of the mimetic nature of the young lovers’ desires. Surprise, surprise. Each individual competes with another one for the recognition or love of a third party. Girard argues that this kind of competition is eventually based on mimetic (i.e. imitative) interplays, and he demonstrates how Shakespeare, throughout his works, developed fundamental insights in this essential human interaction. The lovers in A Midsummer Night’s Dream don’t compete with each other because they accidentally desire the same person, but they desire the same person because they imitate one another. They are led by mimetic desire. Ever more rapidly during the play they all take another person as model or mediator for their desire. This results in self-loathing (a form of auto-aggression) and divinization of their model on the one hand, or in self-aggrandizement and loathing (a form of hetero-aggression) of their model on the other. In the words of Hermia, which summarize the guiding mimetic principles of the play (in Act I, Scene 1):

I will focus on the subplot of the four young Athenian lovers. René Girard, in the aforementioned book A Theater of Envy, interprets the love shenanigans during the fairy night as consequences of the mimetic nature of the young lovers’ desires. Surprise, surprise. Each individual competes with another one for the recognition or love of a third party. Girard argues that this kind of competition is eventually based on mimetic (i.e. imitative) interplays, and he demonstrates how Shakespeare, throughout his works, developed fundamental insights in this essential human interaction. The lovers in A Midsummer Night’s Dream don’t compete with each other because they accidentally desire the same person, but they desire the same person because they imitate one another. They are led by mimetic desire. Ever more rapidly during the play they all take another person as model or mediator for their desire. This results in self-loathing (a form of auto-aggression) and divinization of their model on the one hand, or in self-aggrandizement and loathing (a form of hetero-aggression) of their model on the other. In the words of Hermia, which summarize the guiding mimetic principles of the play (in Act I, Scene 1):

O hell! to choose love by another’s eyes.

Of course, no one is eager to admit that his or her desire is not his or her own. Although the play at first glance lends itself to a romantic interpretation of the ties between the four lovers, Shakespeare comically undermines the belief in “true love” and “true love’s desire” (understood as “unmediated desire”). In the words of René Girard (A Theater of Envy, p.34-35 & p.36-37):

The history of the night continues its prehistory with different characters in the various mimetic roles. Before the midsummer night began, in other words, it had already begun. First Demetrius was unfaithful to Helena, then Hermia was unfaithful to Demetrius, then Lysander to Hermia, and finally Demetrius to Hermia. The four infidelities are arranged in such a way that the minimum number of incidents illustrates the maximum amount of mimetic theory.

It is important to observe that the love juice cannot be invoked as an excuse for the infidelities that occur before the midsummer night. Everything can and must be explained mimetically, that is, rationally. If we had only the infidelities that occur before our eyes, the examples would be too few to lead us unquestionably to the mimetic law, but the addition of the prehistory and the history is sufficient to the purpose. So instead of a single triangular conflict that remains unchanged until the conclusion, A Midsummer Night’s Dream suggests a kaleidoscope, a number of combinations that generate one another at an accelerating pace. Shakespeare gives several objects in succession to the same mimetic rivals for a comic demonstration of the mediator’s predominance in the triangle of mimetic desire.

[…]

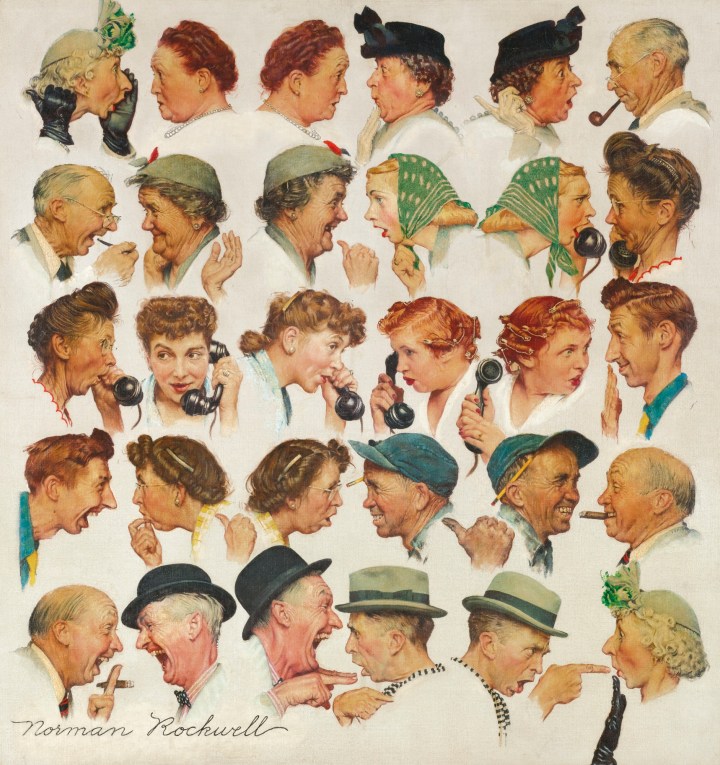

Shakespeare satirizes a society of would-be individualists completely enslaved to one another. He is mocking a desire that always seeks to differentiate and distinguish itself through the imitation of someone else but always achieves the opposite result: A Midsummer Night’s Dream is an early triumph of unisex and uni-everything else. It involves a process of increasing symmetry among all characters, yet not so obviously perfect a one that the demonstration becomes heavy-handed.

Shakespeare satirizes a society of would-be individualists completely enslaved to one another. He is mocking a desire that always seeks to differentiate and distinguish itself through the imitation of someone else but always achieves the opposite result: A Midsummer Night’s Dream is an early triumph of unisex and uni-everything else. It involves a process of increasing symmetry among all characters, yet not so obviously perfect a one that the demonstration becomes heavy-handed.

Unlike the skeptical Puck, who mocks the lovers because he understands everything, Oberon is full of reverence for “true love,” but his language plays occasional tricks upon him and suggests the very reverse of what he intends to say. After Puck has picked the wrong man for his dispensations of love juice, Oberon sounds indignant, as if the difference between “true” and “false” love were so huge that Puck’s mistaking the two were unforgivable. His actual words suggest the very reverse [from Act III, Scene 2]:

What hast thou done? thou hast mistaken quite

And laid the love-juice on some true-love’s sight:

Of thy misprision must perforce ensue

Some true love turn’d and not a false turn’d true.

Who will tell the difference between some “true love turned” and “a false turned true”? It all sounds the same, and the distinction upon which the pious Oberon insists is humorously undermined. The supposed discrepancy between “true love” and its mimetic counterfeit echoes the inferiority of the copy versus the original in traditional aesthetics. The problem is that no original is available: everything is imitation.

The cacophonic circularity of “true love turned” and “false turned true” ironically suggests the paradoxical contribution of differential and individualistic ideologies to the growing mimetic uniformity; differentialism is the ideology of the mimetic urge at its most comically self-defeating. All this amazingly resembles our own contemporary world.

THE AUTO-AGGRESSION OF HELENA

The first mimetic triangle we encounter in the play structures itself from Helena’s perspective. Helena compares herself to Hermia and this reinforces her desire to obtain (the recognition of) Demetrius – the object of her desire [the left side of the diagram]. All this eventually results in Helena’s self-loathing (a form of auto-aggression) and the divinization of her “model”, Hermia – Helena wants to erase (the confrontation with) the difference between herself and Hermia, she wants to be Hermia [the right side of the diagram]. The desire for Hermia’s being – the mediator – turns out to be more important than the desire for Demetrius.

Again, in the words of Girard himself (ibid., p.43-44):

Being is what mimetic desire is really after, and Helena says so explicitly.

Helena wants to be “translated” to Hermia.

[…]

Helena is desperately in love with Demetrius, but he is hardly mentioned; gigantic in the absence of Hermia, his stature shrinks to almost nothing in her presence. Thus the real priorities of mimetic desire are revealed: however desirable the object may be, it pales in comparison with the model who gives it its value.

A remarkable aspect of our text is its sensuousness. Helena wants to catch Hermia’s “favour” as she would a disease, contagiously, through physical contact. She wants every part of her body to match Hermia’s corresponding part. She wants the whole body of Hermia. The homosexual connotations of this text are not “unconscious” but deliberate, and it is difficult to see what kind of help psychoanalysis could provide. Shakespeare portrays the tendency of unsuccessful desire to focus more and more on the cause of its failure and to turn the mediator into a second erotic object – necessarily homosexual, if the original desire is heterosexual; the erotic rival is an individual of the same sex as the subject. The homosexual connotations are inseparable from the growing emphasis on the mediator.

A remarkable aspect of our text is its sensuousness. Helena wants to catch Hermia’s “favour” as she would a disease, contagiously, through physical contact. She wants every part of her body to match Hermia’s corresponding part. She wants the whole body of Hermia. The homosexual connotations of this text are not “unconscious” but deliberate, and it is difficult to see what kind of help psychoanalysis could provide. Shakespeare portrays the tendency of unsuccessful desire to focus more and more on the cause of its failure and to turn the mediator into a second erotic object – necessarily homosexual, if the original desire is heterosexual; the erotic rival is an individual of the same sex as the subject. The homosexual connotations are inseparable from the growing emphasis on the mediator.

Helena will show a little later that she has not forgotten Demetrius; her behavior with him is more “masochistically” erotic during the night than that of any other character.

[…]

What Helena is going through is part of her “midsummer night.” Many adolescents experience an intense fascination for successful school friends, and it may or it may not affect them permanently.

Girard explores the love/hate – dynamics generated by the mimetic interactions between the four lovers more extensively further on (ibid., p.50-51):

We must examine a striking feature in the amorous language of A Midsummer Night’s Dream: the proliferation of animal images. In order to express her self-abasement, Helena compares herself to various beasts. In opposition to these metaphors of lowliness, images of sublimity and divinity express the transcendence of the inaccessible object, Demetrius, and of the triumphant mediator, Hermia.

[…]

In all intensely mimetic relations, the subject tries to combat the self-contempt that necessarily accompanies the overvaluation of the mediator. Helena reveres her mediator but also hates her as a rival, and vainly tries to regain the upper hand in a relationship that has become completely unbalanced. The more divine Hermia and Demetrius seem to Helena, the more beastly she herself feels. The animal images are a privileged means of expressing the self-abasement that mimetic desire generates. Instead of rising to the near-divinity that they perceive in their models, the subjects of desire sink to the level of animality.

It’s time to put Girard’s analysis to the test and to take a look at how The Bard himself portrays Helena’s self-loathing in relation to Hermia and Demetrius.

From Act I, Scene I

HERMIA

God speed fair Helena! whither away?

HELENA

Call you me fair? that fair again unsay.

Demetrius loves your fair: O happy fair!

Your eyes are lode-stars; and your tongue’s sweet air

More tuneable than lark to shepherd’s ear,

When wheat is green, when hawthorn buds appear.

Sickness is catching: O, were favour so,

Yours would I catch, fair Hermia, ere I go;

My ear should catch your voice, my eye your eye,

My tongue should catch your tongue’s sweet melody.

Were the world mine, Demetrius being bated,

The rest I’d give to be to you translated.

O, teach me how you look, and with what art

You sway the motion of Demetrius’ heart.

HERMIA

I frown upon him, yet he loves me still.

HELENA

O that your frowns would teach my smiles such skill!

HERMIA

I give him curses, yet he gives me love.

HELENA

O that my prayers could such affection move!

HERMIA

The more I hate, the more he follows me.

HELENA

The more I love, the more he hateth me.

HERMIA

His folly, Helena, is no fault of mine.

HELENA

None, but your beauty: would that fault were mine!

HERMIA

HERMIA

Take comfort: he no more shall see my face;

Lysander and myself will fly this place.

Before the time I did Lysander see,

Seem’d Athens as a paradise to me:

O, then, what graces in my love do dwell,

That he hath turn’d a heaven unto a hell!

From Act II, Scene I

DEMETRIUS

I love thee not, therefore pursue me not.

Where is Lysander and fair Hermia?

The one I’ll slay, the other slayeth me.

Thou told’st me they were stolen unto this wood;

And here am I, and wode within this wood,

Because I cannot meet my Hermia.

Hence, get thee gone, and follow me no more.

HELENA

You draw me, you hard-hearted adamant;

But yet you draw not iron, for my heart

Is true as steel: leave you your power to draw,

And I shall have no power to follow you.

DEMETRIUS

Do I entice you? do I speak you fair?

Or, rather, do I not in plainest truth

Tell you, I do not, nor I cannot love you?

HELENA

And even for that do I love you the more.

I am your spaniel; and, Demetrius,

The more you beat me, I will fawn on you:

Use me but as your spaniel, spurn me, strike me,

Neglect me, lose me; only give me leave,

Unworthy as I am, to follow you.

What worser place can I beg in your love,–

And yet a place of high respect with me,–

Than to be used as you use your dog?

One of the strongest arguments for the kind of interpretation of the play we’ve been exploring, i.e. in terms of mimetic interactions, is Girard’s reference to what happened before the play begins. The prehistory of the midsummer night is summarized in the very first scene of the play. Girard (ibid., p.33-34):

In the beginning Helena was in love with Demetrius and Demetrius with her. This happy state of affairs did not last. The gentle Helena explains in a soliloquy that her love affair was destroyed by Hermia:

For ere Demetrius look’d on Hermia’s eyne,

He hail’d down oaths that he was only mine;

And when this hail some heat from Hermia felt,

So he dissolved, and showers of oaths did melt.

Why should Hermia attempt to seduce Demetrius away from her best friend? Since Hermia now wants to marry the other boy, Lysander, she could not be motivated by genuine “true love.” What else could it be? Do we have to ask? The mimetic nature of the enterprise is suggested by the close similarity […] with The Two Gentlemen of Verona. Hermia and Helena are the same type of friends as Valentine and Proteus: they have lived together since infancy; they have been educated together; they always act, think, feel, and desire alike.

In our prehistory we have a first mimetic triangle. […]

Demetrius is still very much in love with Hermia because she is the one who jilted him, just as Demetrius himself had jilted Helena a little before. The enterprising Hermia first stole the lover of her best friend and then lost interest in him, thus making two people hysterically unhappy instead of one. If Hermia lived in our time, she would probably claim that a bright, modern, independent young woman like herself needs “more challenging friends” than Demetrius and Helena. Demetrius and Helena seem insufficiently challenging to Hermia because she found it too easy to dominate them. First, she roundly defeated Helena in the battle for Demetrius, which destroyed the prestige of this friend as a mediator. Being no longer transfigured by the power of mimetic rivalry, Demetrius too lost his prestige and did not seem desirable any longer. Whenever an imitator successfully appropriates the object designated by his or her model, the transfiguration machine ceases to function. With no threatening rival in sight, Hermia found Demetrius uninspiring and turned to the more exotic Lysander.

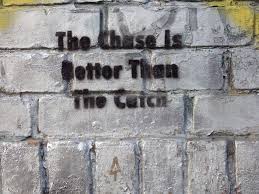

This explanation is also valid for Demetrius, our first example of infidelity. He yielded to Hermia’s blandishments because Helena was too gentle and loving; she did not make things difficult enough for her lover. When mimetic desire is thwarted, it intensifies and, when it succeeds, it withers away. A Midsummer Night’s Dream is the play in which these two aspects are discreetly but systematically exploited. The two together make up the dynamics of the midsummer night.

THE HETERO- (AND AUTO-) AGGRESSION OF HERMIA

Indeed, from the observations about the prehistory of the midsummer night it is plausible to consider the alternative love triangle at the climax of the midsummer night as a consequence of (Shakespeare’s insight into) mimetic logic. Puck’s love potion hardly conceals Shakespeare’s deconstruction of the “true love” illusion. The reality of mimetic desire brings any stable “forever and ever” romanticism to an end. Once again, René Girard (ibid., p.51):

As the end approaches, the metaphysical absolute shifts from character to character and the mimetic relation loses all stability. When the two boys abandon Hermia and turn to Helena, the entire configuration is reorganized on the basis of the same polarities but with a new distribution of roles. A formerly despised member of the group has become its idol, and a former idol has lost all prestige; in the language of our metaphoric polarity, it really means that a beast has turned into a god and, reciprocally, a god has turned into a beast. Up is down and down is up. When Lysander and Demetrius fall in love with Helena, it is Hermia’s turn to feel like a dog.

As the end approaches, the metaphysical absolute shifts from character to character and the mimetic relation loses all stability. When the two boys abandon Hermia and turn to Helena, the entire configuration is reorganized on the basis of the same polarities but with a new distribution of roles. A formerly despised member of the group has become its idol, and a former idol has lost all prestige; in the language of our metaphoric polarity, it really means that a beast has turned into a god and, reciprocally, a god has turned into a beast. Up is down and down is up. When Lysander and Demetrius fall in love with Helena, it is Hermia’s turn to feel like a dog.

The diagram from the perspective of Hermia thus looks like this:

Helena cannot believe that the two boys now rival each other to obtain her (all the while, of course, mimetically reinforcing each other’s desire). Of course Hermia is not happy with this turn of events. At the same time as she “masochistically” loathes her own “dwarfish stature”, she loathes Helena. Hermia, comparing herself with Helena, is even prepared to fight her friend. The Bard:

From Act III, Scene II

HELENA

O spite! O hell! I see you all are bent

To set against me for your merriment:

If you were civil and knew courtesy,

You would not do me thus much injury.

Can you not hate me, as I know you do,

But you must join in souls to mock me too?

If you were men, as men you are in show,

You would not use a gentle lady so;

To vow, and swear, and superpraise my parts,

When I am sure you hate me with your hearts.

You both are rivals, and love Hermia;

And now both rivals, to mock Helena:

A trim exploit, a manly enterprise,

To conjure tears up in a poor maid’s eyes

With your derision! none of noble sort

Would so offend a virgin, and extort

A poor soul’s patience, all to make you sport.

[…]

HERMIA

What, can you do me greater harm than hate?

Hate me! wherefore? O me! what news, my love!

Am not I Hermia? are not you Lysander?

I am as fair now as I was erewhile.

Since night you loved me; yet since night you left me:

Why, then you left me–O, the gods forbid!–

In earnest, shall I say?

LYSANDER

Ay, by my life;

And never did desire to see thee more.

Therefore be out of hope, of question, of doubt;

Be certain, nothing truer; ’tis no jest

That I do hate thee and love Helena.

HERMIA

O me! you juggler! you canker-blossom!

You thief of love! what, have you come by night

And stolen my love’s heart from him?

HELENA

Fine, i’faith!

Have you no modesty, no maiden shame,

No touch of bashfulness? What, will you tear

Impatient answers from my gentle tongue?

Fie, fie! you counterfeit, you puppet, you!

HERMIA

Puppet? why so? ay, that way goes the game.

Now I perceive that she hath made compare

Between our statures; she hath urged her height;

And with her personage, her tall personage,

Her height, forsooth, she hath prevail’d with him.

And are you grown so high in his esteem;

Because I am so dwarfish and so low?

How low am I, thou painted maypole? speak;

How low am I? I am not yet so low

But that my nails can reach unto thine eyes.

THE HETERO-AGGRESSION OF DEMETRIUS

Finally, the mimetic logic is also at work in the behavior of the two boys. René Girard (ibid., p.32-33):

The first thing to observe is that, even though the two boys are never in love with any girl for very long, both of them at any given time are always in love with the same girl. We can also observe great similarities in their two discourses, which remain unchanged when both of them shift from one girl to the other, except, of course, for the minor adjustments required by the fact that Helena is a tall blonde, whereas Hermia is short and dark-haired.

[…]

[Demetrius] imitates Lysander because Lysander took Hermia away from him, and like all defeated rivals, he is horribly mediated by his victorious opponent. His desire for Hermia remains intense as long as Lysander provides it with a model; as soon as Lysander shifts to Helena, Demetrius also shifts. This perfect parrot is a more comic version of Proteus [from The Two Gentlemen of Verona]. Imitation is so compulsive with him that, were there a third girl in the group, he would certainly fall in love with her, but not before Lysander did.

In short, Demetrius compares himself to Lysander, and this reinforces his desire for Hermia [the left side of the diagram]. All this results in Demetrius’ desire to erase (the confrontation with the difference between him and) Lysander [the right side of the diagram]. Hence the full diagram:

In the words of The Bard:

From Act II, Scene I

DEMETRIUS

I love thee not, therefore pursue me not.

Where is Lysander and fair Hermia?

The one I’ll slay, the other slayeth me.

Thou told’st me they were stolen unto this wood;

And here am I, and wode within this wood,

Because I cannot meet my Hermia.

Hence, get thee gone, and follow me no more.

HELENA

You draw me, you hard-hearted adamant;

But yet you draw not iron, for my heart

Is true as steel: leave you your power to draw,

And I shall have no power to follow you.

THE HETERO-AGGRESSION OF LYSANDER

Lysander at first seems more independent than Demetrius, but we should not be fooled. René Girard (ibid., p.33-34):

What about Lysander himself? When he shifts to Helena, he has no possible model, since no one is in love with the poor girl. Does that mean that his desire is truly spontaneous?

[…]

In The Two Gentlemen of Verona, Shakespeare emphasized the strength and stability of unfulfilled desire. In A Midsummer Night’s Dream this emphasis remains, but it is supplemented by an equal emphasis on the instability of fulfilled desire. We can now understand why Lysander abandons Hermia, for all desertions are rooted in the disenchantment of peaceful possession. Lysander has triumphed over his mimetic rival Demetrius. Hermia truly belongs to him, so he lacks the indispensable stimulus of mimetic rivalry. Helena must seem attractive at this point because she has given no indication of being interested in Lysander; besides, there is no one else to turn to.

In The Two Gentlemen of Verona, Shakespeare emphasized the strength and stability of unfulfilled desire. In A Midsummer Night’s Dream this emphasis remains, but it is supplemented by an equal emphasis on the instability of fulfilled desire. We can now understand why Lysander abandons Hermia, for all desertions are rooted in the disenchantment of peaceful possession. Lysander has triumphed over his mimetic rival Demetrius. Hermia truly belongs to him, so he lacks the indispensable stimulus of mimetic rivalry. Helena must seem attractive at this point because she has given no indication of being interested in Lysander; besides, there is no one else to turn to.

In other words, Lysander compares himself to Demetrius and reinforces his desire for (the recognition of) Helena, to the point where he wants to get rid of Demetrius. Hence the diagram:

From Act II, Scene II

HELENA

O, I am out of breath in this fond chase!

The more my prayer, the lesser is my grace.

Happy is Hermia, wheresoe’er she lies;

For she hath blessed and attractive eyes.

How came her eyes so bright? Not with salt tears:

If so, my eyes are oftener wash’d than hers.

No, no, I am as ugly as a bear;

For beasts that meet me run away for fear:

Therefore no marvel though Demetrius

Do, as a monster fly my presence thus.

What wicked and dissembling glass of mine

Made me compare with Hermia’s sphery eyne?

But who is here? Lysander! on the ground!

Dead? or asleep? I see no blood, no wound.

Lysander if you live, good sir, awake.

LYSANDER

[Awaking] And run through fire I will for thy sweet sake.

Transparent Helena! Nature shows art,

That through thy bosom makes me see thy heart.

Where is Demetrius? O, how fit a word

Is that vile name to perish on my sword!

HELENA

Do not say so, Lysander; say not so

What though he love your Hermia? Lord, what though?

Yet Hermia still loves you: then be content.

LYSANDER

Content with Hermia! No; I do repent

The tedious minutes I with her have spent.

Not Hermia but Helena I love:

Who will not change a raven for a dove?

The will of man is by his reason sway’d;

And reason says you are the worthier maid.

Things growing are not ripe until their season

So I, being young, till now ripe not to reason;

And touching now the point of human skill,

Reason becomes the marshal to my will

And leads me to your eyes, where I o’erlook

Love’s stories written in love’s richest book.

3. MIMESIS AND EROS

Without further ado, René Girard’s main conclusion on A Midsummer Night’s Dream (ibid., p.64):

The symmetry of the two human subplots suggests that aesthetic imitation and the mimetic Eros are two modalities of the same principle. Bottom’s desire for mimesis spreads as contagiously among the craftsmen as erotic desire among the lovers and has the same disruptive effects upon the two groups; it produces the same mythology [the midsummer night’s dream].

In his theatrical subplot, Shakespeare reinjects the ingredient that the aestheticians always leave out – competitive desire. In the lovers’ subplot he reinjects the ingredient that the students of desire never take into account – imitation. This double restitution turns the two subplots into faithful mirrors of each other, the two complementary halves of a single challenge against the Western philosophical and anthropological tradition.

[…]

The enormous force of Shakespeare comes from his ability to rid himself of two bad abstractions simultaneously: solipsistic desire and the bland, disembodied imitation of the aestheticians. The love of mimesis that sustains the aesthetic enterprise is one and the same with mimetic desire. This is the real message of A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

The Western philosophical and scientific tradition is based on the opposite principle. Mimesis and Eros are seen as separate. The myth of their mutual independence goes back to Plato, who never associates the two concepts, even though his frantic fear of mimetic contagion and his distrust of art, more particularly of the theater, points to the unity that his formal system repudiates.

[…]

Shakespeare’s spectacular marriage of mimesis and desire is the unity of the three subplots and the unity of A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

__________________________________________________________________________________

The play ends with Puck addressing the audience. It seems he tries to reassure us that “true love” can only be disturbed by a magical dream. As if a certain configuration of relationships is true and “real” and an alternative one can only be false and “dreamlike appearance”. We don’t like to admit that our desires are subject to mimetic antics. We would like to escape the realization that our desires are guided by emotions like envy and jealousy, or pride. And yet, Puck ironically reveals that there indeed is a “serpent’s tongue” (i.e. the principle of mimetic comparing, as the serpent refers to the creature that seduces Adam and Eve to compare themselves to God in the Genesis story of the Garden of Eden). Thus Puck is the liar (“merely a character in a play”) who tells the truth. And so he gets the last laugh…

From Act V, Scene I

PUCK

PUCK

If we shadows have offended,

Think but this, and all is mended,

That you have but slumber’d here

While these visions did appear.

And this weak and idle theme,

No more yielding but a dream,

Gentles, do not reprehend:

if you pardon, we will mend:

And, as I am an honest Puck,

If we have unearned luck

Now to ‘scape the serpent’s tongue,

We will make amends ere long;

Else the Puck a liar call;

So, good night unto you all.

Give me your hands, if we be friends,

And Robin shall restore amends.

CLICK HERE FOR A PDF-FILE OF THE DIAGRAMS

Here are some previous posts concerning the same issues:

- Mimetic Theory in High School (click to read)

- Types of the Scapegoat Mechanism (click to read)

- Scapegoating in American Beauty (click to read)

- Philosophy in American Beauty (click to read)

- Real Life Cases of Ressentiment (click to read)

- Eminem Reads the Bible (click to read)

- The Grace of Prostitutes (click to read)

See also: Achever… the Social Sciences (click to read)

The writings of Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Levinas are not always easy to understand, let alone agree with. Roger Burggraeve, one of my professors at the University of Leuven, has proven to be an excellent guide to introduce me to the philosophy of Levinas (click here for an excellent summary by Burggraeve). But explanations at an academic level are not always easily transferable to a high school level. Regarding Levinas I’m faced with the challenge to explain something about his thoughts on “the Other” and “the Other’s face”. Although Levinas’ musings often appear to be highly abstract for someone who didn’t receive any proper philosophical training, his thinking springs from very “earthly”, even dark realities and experiences – especially the experience of the Holocaust. Levinas’ response to the threat of totalitarianism is actually very down to earth, but because it wants to be “fundamental”, I can imagine it indeed sometimes comes across as mumbo-jumbo to sixteen year olds.

The writings of Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Levinas are not always easy to understand, let alone agree with. Roger Burggraeve, one of my professors at the University of Leuven, has proven to be an excellent guide to introduce me to the philosophy of Levinas (click here for an excellent summary by Burggraeve). But explanations at an academic level are not always easily transferable to a high school level. Regarding Levinas I’m faced with the challenge to explain something about his thoughts on “the Other” and “the Other’s face”. Although Levinas’ musings often appear to be highly abstract for someone who didn’t receive any proper philosophical training, his thinking springs from very “earthly”, even dark realities and experiences – especially the experience of the Holocaust. Levinas’ response to the threat of totalitarianism is actually very down to earth, but because it wants to be “fundamental”, I can imagine it indeed sometimes comes across as mumbo-jumbo to sixteen year olds. At one moment, near the end of Will and Carlton’s fight, something happens which indeed illustrates what Levinas means with “response to the Other’s face” (click here for some excerpts from Levinas’ Ethics as First Philosophy). Will pretends to be severely injured (“My eye!”), whereon Carlton totally withdraws from the fight. Carlton finds himself confronted with Will’s vulnerability, and is genuinely concerned for his nephew’s well-being. The Other he was fighting turns out to be more than his rival, more than the product of his (worst) imaginations. Indeed, before being a rival the Other “is simply there“, not reducible to any of our concerns, desires or anxieties. Carlton is not concerned for his own sake: he doesn’t seem to fear any punishment, nor does he seem to desire any reward while showing his care for Will. He abandons all actions of self-interest “in the wink of an eye”.

At one moment, near the end of Will and Carlton’s fight, something happens which indeed illustrates what Levinas means with “response to the Other’s face” (click here for some excerpts from Levinas’ Ethics as First Philosophy). Will pretends to be severely injured (“My eye!”), whereon Carlton totally withdraws from the fight. Carlton finds himself confronted with Will’s vulnerability, and is genuinely concerned for his nephew’s well-being. The Other he was fighting turns out to be more than his rival, more than the product of his (worst) imaginations. Indeed, before being a rival the Other “is simply there“, not reducible to any of our concerns, desires or anxieties. Carlton is not concerned for his own sake: he doesn’t seem to fear any punishment, nor does he seem to desire any reward while showing his care for Will. He abandons all actions of self-interest “in the wink of an eye”. Do you agree, however, that movies, TV and advertising draw heavily on mimetic principle, therefore increasing our awareness on this score?

Do you agree, however, that movies, TV and advertising draw heavily on mimetic principle, therefore increasing our awareness on this score? g painful self-criticism in the spectators. This is what this show did. People do not have to understand fully in order to appreciate. They must not understand. They identify themselves with what these characters do because they do it too. They recognize something that is very common and very true, but they cannot define it. Probably the contemporaries of Shakespeare appreciated his portrayal of human relations in the same way we enjoy Seinfeld, without really understanding his perspicaciousness regarding mimetic interaction. I must say that there is more social reality in Seinfeld than in most academic sociology.”

g painful self-criticism in the spectators. This is what this show did. People do not have to understand fully in order to appreciate. They must not understand. They identify themselves with what these characters do because they do it too. They recognize something that is very common and very true, but they cannot define it. Probably the contemporaries of Shakespeare appreciated his portrayal of human relations in the same way we enjoy Seinfeld, without really understanding his perspicaciousness regarding mimetic interaction. I must say that there is more social reality in Seinfeld than in most academic sociology.” The title itself can already be connected to a basic concept of René Girard’s mimetic theory, namely mimetic desire. As it turns out, “triangulation” indeed refers to the triangular nature of human desire (beyond instinctive needs) as described by Girard: the desire of a subject towards a certain object is positively or negatively influenced by mediators or models (click here to watch an example of negatively mediated desire from another popular sitcom, Seinfeld). Humans imitate others in orienting their desires – their desire thus is mimetic.

The title itself can already be connected to a basic concept of René Girard’s mimetic theory, namely mimetic desire. As it turns out, “triangulation” indeed refers to the triangular nature of human desire (beyond instinctive needs) as described by Girard: the desire of a subject towards a certain object is positively or negatively influenced by mediators or models (click here to watch an example of negatively mediated desire from another popular sitcom, Seinfeld). Humans imitate others in orienting their desires – their desire thus is mimetic.

Several lines of evidence indicate some female competition over mating. First, at Mahale, females sometimes directly interfered in the mating attempts of their rivals by forcing themselves between a copulating pair. In some cases, the aggressive female went on to mate with the male. At Gombe, during a day-long series of attacks by Mitumba females on a fully swollen new immigrant female, the most active attackers were also swollen and their behaviour was interpreted as ‘sexual jealousy’ by the observers. Townsend et al. found that females at Budongo suppressed copulation calls when in the presence of the dominant female, possibly to prevent direct interference in their copulations. Second, females occasionally seem to respond to the sexual swellings of others by swelling themselves. Goodall described an unusual incident in which a dominant, lactating female suddenly appeared with a full swelling a day after a young oestrous female had been followed by many males. Nishida described cases at Mahale in which a female would produce isolated swellings that were not part of her regular cycles when a second oestrous female was present in the group.

Several lines of evidence indicate some female competition over mating. First, at Mahale, females sometimes directly interfered in the mating attempts of their rivals by forcing themselves between a copulating pair. In some cases, the aggressive female went on to mate with the male. At Gombe, during a day-long series of attacks by Mitumba females on a fully swollen new immigrant female, the most active attackers were also swollen and their behaviour was interpreted as ‘sexual jealousy’ by the observers. Townsend et al. found that females at Budongo suppressed copulation calls when in the presence of the dominant female, possibly to prevent direct interference in their copulations. Second, females occasionally seem to respond to the sexual swellings of others by swelling themselves. Goodall described an unusual incident in which a dominant, lactating female suddenly appeared with a full swelling a day after a young oestrous female had been followed by many males. Nishida described cases at Mahale in which a female would produce isolated swellings that were not part of her regular cycles when a second oestrous female was present in the group.

“

“ And the devil. And this is what people believed.

And the devil. And this is what people believed.

At first you called me gay behind my back

At first you called me gay behind my back

In een chronologisch later fragment beklaagt Louis Seynaeve zich over het lot van de joden, voor wie hij gaandeweg meer sympathie krijgt. Louis is in gesprek met zijn Papa, die daarentegen sympathiseert met de Duitse vijand – pp. 516-517:

In een chronologisch later fragment beklaagt Louis Seynaeve zich over het lot van de joden, voor wie hij gaandeweg meer sympathie krijgt. Louis is in gesprek met zijn Papa, die daarentegen sympathiseert met de Duitse vijand – pp. 516-517:

The noise of which spread everywhere around;

The noise of which spread everywhere around;