1. NARCISSIST OR REALIST?

Bob doesn’t care about what other people might say or think of him. He knows that he can sing, even when the different juries of The Voice, Idol, X Factor and America’s Got Talent claim that his qualities lie elsewhere. Bob’s stubborn belief in himself would be admirable if it wasn’t so tragicomic. It is clear to the television audience as well that he sings totally out of tune. Apparently, however, he cannot accept this reality because his sense of self-worth fully depends on illusory self-concepts. After yet one more negative judgment by a jury he storms out of the audition room, even more proud than before. It is clear that Bob is a prime example of a narcissist. He is not capable of loving himself and of accepting his limitations. He rather drowns in his megalomania, convinced that the judgment of “the others” and their perception of his “faults” are based on ignorance. Of course, the reason why the narcissist becomes angry precisely is due to the fact that he does indeed desire the approval by others. So, paradoxically, when the narcissist cries “I don’t need your affirmation” he actually no longer fully hides that he secretly and desperately needs the affirmation. In order to be able to deal with his own situation, however, he must convince himself that he doesn’t need the others who don’t affirm his self-image.

Bob doesn’t care about what other people might say or think of him. He knows that he can sing, even when the different juries of The Voice, Idol, X Factor and America’s Got Talent claim that his qualities lie elsewhere. Bob’s stubborn belief in himself would be admirable if it wasn’t so tragicomic. It is clear to the television audience as well that he sings totally out of tune. Apparently, however, he cannot accept this reality because his sense of self-worth fully depends on illusory self-concepts. After yet one more negative judgment by a jury he storms out of the audition room, even more proud than before. It is clear that Bob is a prime example of a narcissist. He is not capable of loving himself and of accepting his limitations. He rather drowns in his megalomania, convinced that the judgment of “the others” and their perception of his “faults” are based on ignorance. Of course, the reason why the narcissist becomes angry precisely is due to the fact that he does indeed desire the approval by others. So, paradoxically, when the narcissist cries “I don’t need your affirmation” he actually no longer fully hides that he secretly and desperately needs the affirmation. In order to be able to deal with his own situation, however, he must convince himself that he doesn’t need the others who don’t affirm his self-image.

Two thousand years ago, there’s a man walking around in Palestine, a certain Jesus of Nazareth, who also doesn’t seem to care too much about the judgment of his fellow men – in his case his co-national Jews, most of the time. A “jury” of Jewish notables (including scribes and chief priests) repudiates him when he shares a meal with “tax collectors and sinners” (see for example Luke 15:1-2). Or whenever he involves himself with the sick or with “the pagans”, those who are said to be cursed by God. Eventually his opponents utter a critique that is echoed centuries later by German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900): Jesus is the ultimate seducer of people with low self-esteem. It is all too easy to make yourself popular among people who feel humiliated, marginalized or insecure by telling them that they are loved by God.

If Jesus isn’t acknowledged by the rulers of his time, then this is compensated largely by the approval he receives from the common people. It’s something Bob can only dream of. He has to get through with the comforting approval of merely a handful of friends. Maybe there’s even a manipulator among them who makes Bob emotionally dependent on the positive attention he grants Bob. In any case, Jesus seems to be a bigger and much more refined attention whore than Bob will ever be. The social elite even considers Jesus’ growing popularity as a threat to the survival of the Jewish nation. Driven by a mad lust for power, Jesus indeed could launch an already lost revolution against the Roman occupiers. That’s why the Jewish leaders are convinced that Jesus has to disappear.

This reasoning, that tries to justify the execution of Jesus, is not bought by everyone. The Gospels claim that envy is the true motivation of Jesus’ adversaries (Mark 15:10, Matthew 27:18): jealous of the popularity of Jesus, and themselves driven by a vain desire for prestige, they want to get rid of Jesus. Even when the Gospels would be right about this, Jesus perhaps still remains the “Über-narcissist”. Many times worse than poor Bob. Indeed, the moment Jesus is judged and abandoned by nearly everyone, he is yet able to convince himself that he is loved by an imaginary friend – his divine “daddy”, his “Abba”. And what is the love of men compared to the love of a God? It seems Jesus is prepared to endure the worst of sufferings in order to gain a sacred hero position. In short, from this perspective Jesus appears as a totally nuts, narcissistic masochist who would rather die for an imaginary sadist than accept that he is worth nothing. He has no choice but to leave this world as a “disregarded genius” and to choose a so-called “divine dimension” as his true home. Only one time Jesus seems to doubt his megalomaniac construction. Just before his tortured, crucified body gives in, he screams (Matthew 27:46): “Eli, Eli, lema sabachthani?” that is, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” Nevertheless, even then he calls out to a divine daddy who should grant him love and attention.

The thus depicted Jesus – the archetypal narcissist – knows many variants in real individuals throughout history. Besides, Jesus would not be an archetype if not every person suffers from narcissistic tendencies. Of course there are some distinct cases. Bob, for instance. But also the ISIS warrior who turns his back on the world he feels disrespected by and goes to live in a so-called environment “on God’s side”. Or the very insecure girl who locks herself up in the glorification of a shrewd, manipulating guru who satisfies her yearning for acknowledgment. Or someone like Adolf Hitler, who prefers to die instead of facing his defeat.

The thus depicted Jesus – the archetypal narcissist – knows many variants in real individuals throughout history. Besides, Jesus would not be an archetype if not every person suffers from narcissistic tendencies. Of course there are some distinct cases. Bob, for instance. But also the ISIS warrior who turns his back on the world he feels disrespected by and goes to live in a so-called environment “on God’s side”. Or the very insecure girl who locks herself up in the glorification of a shrewd, manipulating guru who satisfies her yearning for acknowledgment. Or someone like Adolf Hitler, who prefers to die instead of facing his defeat.

And yet… When you read the Gospels, you cannot escape the impression that there’s something quite different going on in the case of Jesus of Nazareth compared to the situation of Bob, the ISIS warrior and the insecure girl. Or when you compare Jesus to the shrewd guru and Adolf Hitler. C.S. Lewis (1898-1963) formulates the dilemma quite well in Mere Christianity: “I am trying here to prevent anyone saying the really foolish thing that people often say about Jesus: I’m ready to accept Jesus as a great moral teacher, but I don’t accept his claim to be God. That is the one thing we must not say. A man who was merely a man and said the sort of things Jesus said would not be a great moral teacher. He would either be a lunatic — on the level with the man who says he is a poached egg — or else he would be the Devil of Hell. You must make your choice. Either this man was, and is, the Son of God, or else a madman or something worse. You can shut him up for a fool, you can spit at him and kill him as a demon or you can fall at his feet and call him Lord and God, but let us not come with any patronizing nonsense about his being a great human teacher. He has not left that open to us. He did not intend to.”

And yet… When you read the Gospels, you cannot escape the impression that there’s something quite different going on in the case of Jesus of Nazareth compared to the situation of Bob, the ISIS warrior and the insecure girl. Or when you compare Jesus to the shrewd guru and Adolf Hitler. C.S. Lewis (1898-1963) formulates the dilemma quite well in Mere Christianity: “I am trying here to prevent anyone saying the really foolish thing that people often say about Jesus: I’m ready to accept Jesus as a great moral teacher, but I don’t accept his claim to be God. That is the one thing we must not say. A man who was merely a man and said the sort of things Jesus said would not be a great moral teacher. He would either be a lunatic — on the level with the man who says he is a poached egg — or else he would be the Devil of Hell. You must make your choice. Either this man was, and is, the Son of God, or else a madman or something worse. You can shut him up for a fool, you can spit at him and kill him as a demon or you can fall at his feet and call him Lord and God, but let us not come with any patronizing nonsense about his being a great human teacher. He has not left that open to us. He did not intend to.”

In short this dilemma reads as follows (in the light of everything that went before): or Jesus was the ultimate narcissist, or he was the ultimate realist in a human world that time and again threatens to destroy itself because of snobbish vanities, idealistic utopias, sectarian tendencies and “the idolatry of social success”. As the ultimate realist in a human world that is tormented by narcissistic illusions Jesus would indeed be “not of this world”.

2. WHY JESUS OF NAZARETH IS NOT A NARCISSIST

There are reasons to believe that Jesus is not the narcissist he is blamed for.

First of all, Jesus is often precisely the one who confronts people with their own narcissistic tendencies. For instance, when he is surrounded by people who are about to stone a woman caught in the act of adultery (John 8:1-11), Jesus awakens a sense of reality in each individual. He asks people to consider whether they themselves are “without sin”. After which he decides that “whoever is without sin may cast the first stone”. At first sight this is merely a clever trick that allows Jesus to take control of the situation. Indeed, no Jew would claim to be perfect. That would mean that he claims to be like God, and then he would trespass the first of the ten commandments. So no one can cast the first stone, because that would be one of the greatest sins in the light of Jesus’ saying. At a deeper level, it is precisely Jesus’ constant “iconoclasm” of false self-concepts that, apart from the social position Jesus himself receives for doing so, opens up possibilities for new relationships between people.

A second set of arguments against the depiction of Jesus as a narcissist arises. The so-called iconoclasm of Jesus has two aspects, and they immediately clarify how much Jesus differs from gurus who need the manipulated adoration of weak, troubled minds.

On the one hand, concerning the group people are part of and that often manifests itself at the expense of a common enemy (that adulteress, for instance), Jesus sows discord. It is no coincidence that he claims (Matthew 10:34-36): “Do not think that I have come to bring peace to the earth. I have not come to bring peace, but a sword. For I have come to set a man against his father, and a daughter against her mother, and a daughter-in-law against her mother-in-law. And a person’s enemies will be those of his own household.” This intention of Jesus, to create conflict where there is a certain order, is actually and paradoxically a plea against violence. Family members who slavishly obey a pater familias, tribe members who harmoniously feel superior to other groups, criminal gangs who blindly pledge allegiance to the mob boss, cult members and fundamentalist believers who are prepared to fight for their leader till death, anxious employees who sell their soul to keep their job in a sick working environment, (youthful) cliques who strengthen their internal cohesion by bullying someone, whole nations who bow to the demands of a populist dictator and execute so-called “traitors” – Jesus doesn’t like it one bit.

On the one hand, concerning the group people are part of and that often manifests itself at the expense of a common enemy (that adulteress, for instance), Jesus sows discord. It is no coincidence that he claims (Matthew 10:34-36): “Do not think that I have come to bring peace to the earth. I have not come to bring peace, but a sword. For I have come to set a man against his father, and a daughter against her mother, and a daughter-in-law against her mother-in-law. And a person’s enemies will be those of his own household.” This intention of Jesus, to create conflict where there is a certain order, is actually and paradoxically a plea against violence. Family members who slavishly obey a pater familias, tribe members who harmoniously feel superior to other groups, criminal gangs who blindly pledge allegiance to the mob boss, cult members and fundamentalist believers who are prepared to fight for their leader till death, anxious employees who sell their soul to keep their job in a sick working environment, (youthful) cliques who strengthen their internal cohesion by bullying someone, whole nations who bow to the demands of a populist dictator and execute so-called “traitors” – Jesus doesn’t like it one bit.

Opposed to the small and big forms of “peace” based on oppression and violence, of which the Pax Romana in the time of Jesus is an obvious case of course, Jesus challenges people to build peace differently. Family members who belong to a “home” where they can have debates with each other, members of enemy tribes who end age old feuds by questioning their own perception of “the other tribe”, former criminals who start to behave like “moles” to clear their violent Mafia gang, fundamentalists who – realizing what they do to those who supposedly don’t belong to “the chosen ones” – liberate themselves from religious indoctrinations, employees who address a reign of terror at their workplace, individuals who criticize the bullying of their own clique, pacifists who dare to dissent with the violent rule of a dictatorship and unveil its enemy images as grotesque caricatures – Jesus likes it. “Love your enemies”, Jesus says (Matthew 5:44). Everyone who no longer condemns the external enemy of his own particular group because of a stirred up feeling of superiority, generates internal discord: “A person’s enemies will be those of his own household.” It’s only logical.

Opposed to the small and big forms of “peace” based on oppression and violence, of which the Pax Romana in the time of Jesus is an obvious case of course, Jesus challenges people to build peace differently. Family members who belong to a “home” where they can have debates with each other, members of enemy tribes who end age old feuds by questioning their own perception of “the other tribe”, former criminals who start to behave like “moles” to clear their violent Mafia gang, fundamentalists who – realizing what they do to those who supposedly don’t belong to “the chosen ones” – liberate themselves from religious indoctrinations, employees who address a reign of terror at their workplace, individuals who criticize the bullying of their own clique, pacifists who dare to dissent with the violent rule of a dictatorship and unveil its enemy images as grotesque caricatures – Jesus likes it. “Love your enemies”, Jesus says (Matthew 5:44). Everyone who no longer condemns the external enemy of his own particular group because of a stirred up feeling of superiority, generates internal discord: “A person’s enemies will be those of his own household.” It’s only logical.

In short, Jesus argues in favor of non-violent conflict in order to end violent peace. That’s why he can say, eventually (John 14:27): “Peace I leave with you; my peace I give to you. Not as the world gives do I give to you.” Thereby he does not hesitate to re-evaluate and transform existing structures, rather than simply destroy them. This is, moreover, as a result of the first aspect of Jesus’ iconoclasm, a second reason why Jesus should not be characterized as a power-crazed, jealous narcissist. Jesus does not replace the existing, worldly order by imposing his own laws in competition with that order. If that were the case, he would be nothing more than yet another evil and paranoid mastermind conjuring up megalomaniac plots for world domination. The mythological story of Jesus’ temptation by the devil in the desert metaphorically clarifies that Jesus was historically experienced as someone who does not imitate the envious lust for power of his social environment (Matthew 4:8-10):

In short, Jesus argues in favor of non-violent conflict in order to end violent peace. That’s why he can say, eventually (John 14:27): “Peace I leave with you; my peace I give to you. Not as the world gives do I give to you.” Thereby he does not hesitate to re-evaluate and transform existing structures, rather than simply destroy them. This is, moreover, as a result of the first aspect of Jesus’ iconoclasm, a second reason why Jesus should not be characterized as a power-crazed, jealous narcissist. Jesus does not replace the existing, worldly order by imposing his own laws in competition with that order. If that were the case, he would be nothing more than yet another evil and paranoid mastermind conjuring up megalomaniac plots for world domination. The mythological story of Jesus’ temptation by the devil in the desert metaphorically clarifies that Jesus was historically experienced as someone who does not imitate the envious lust for power of his social environment (Matthew 4:8-10):

The devil took Jesus to a very high mountain and showed him all the kingdoms of the world and their glory. And he said to him, “All these I will give you, if you will fall down and worship me.” Then Jesus said to him, “Be gone, Satan! For it is written, ‘You shall worship the Lord your God and him only shall you serve.'”

Jesus is very clear about what he means by “serving God” in a conversation with a lawyer (Matthew 22:35-40):

A lawyer asked Jesus a question to test him. “Teacher, which is the great commandment in the Law?” And Jesus said to him, “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind. This is the great and first commandment. And a second is like it: You shall love your neighbor as yourself. On these two commandments depend all the Law and the Prophets.”

In other words, from a Christian perspective God reveals himself – at least at a human level – in the not directly measurable, invisible reality of love of one’s neighbor. Jesus is convinced that the source from which he lives “desires mercy, and not sacrifice” (Matthew 9:13). The consequences of this conviction are paradoxical. It implies, as already mentioned, that Jesus refuses to merely sacrifice the existing worldly structures in order to establish his own rule. Hence he says (Matthew 5:17):

“Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them.”

The priority of neighborly love implies that existing laws, structures and rituals should be tested against the extent to which they help to avoid making victims and to which they allow for authentic human lives. Man should not live according to rules, as if preserving a social system and its rules would be an end in itself, but rules should be means at the service of individual human beings and society as a whole. When Jesus and his disciples are criticized for doing things that are, strictly speaking, forbidden on the rest day – the Sabbath – Jesus answers (Mark 2:27):

“The Sabbath was made for man, not man for the Sabbath.”

Actually, throughout the Gospels Jesus constantly asks whether people act because of love of oneself and others (what Christian tradition identifies as “acting according to God”), or because of a certain social status that should bring approval (what Christian tradition identifies as “acting for the sake of an idol”). Jesus criticizes the way people behave when their behavior is caused by a desire for approval (Matthew 6:1-6):

“Beware of practicing your righteousness before other people in order to be seen by them, for then you will have no reward from your Father who is in heaven. Thus, when you give to the needy, sound no trumpet before you, as the hypocrites do in the synagogues and in the streets, that they may be praised by others. Truly, I say to you, they have received their reward. But when you give to the needy, do not let your left hand know what your right hand is doing, so that your giving may be in secret. And your Father who sees in secret will reward you. And when you pray, you must not be like the hypocrites. For they love to stand and pray in the synagogues and at the street corners, that they may be seen by others. Truly, I say to you, they have received their reward. But when you pray, go into your room and shut the door and pray to your Father who is in secret. And your Father who sees in secret will reward you.”

At first sight this text can be interpreted as a validation of Jesus’ mad and desperate narcissism: everyone who runs the risk of not being recognized by other people – including Jesus himself – can always count on the approval from an imaginary divine “Dad”. However, the “Father who ís in secret” is love itself that realizes itself independently from the question whether or not it results in “success”. From a Christian point of view the love that allows people to accept themselves and others – and thus “refuses sacrifice” – is not something that produces the approval from God, but it is itself a manifestation of God “at a human level”. The first letter of John very clearly formulates this conviction (1 John 4:7-8):

Beloved, let us love one another, for love is from God, and whoever loves has been born of God and knows God. Anyone who does not love does not know God, because God is love.

Beloved, let us love one another, for love is from God, and whoever loves has been born of God and knows God. Anyone who does not love does not know God, because God is love.

An atheist who still brags about how he “does not need a heavenly reward” in order to “do good” still “sounds the trumpet” about his own “goodness”. The love the Gospels speak of is, by contrast, not always directly visible, and does not depend on visibility. Does a student throw his waste in a dustbin out of respect for his fellow students? Or because he desires the approval of his teachers and, at the same time, because he wants to avoid being punished? Indeed it is not directly visible whether or not a student respects certain rules because of love of one’s neighbor or because of love of one’s image. In the latter case the student will also fear losing his status. In the words of John’s first letter again (1 John 4:18), expressing the difference between the former and latter type of love:

There is no fear in love, but perfect love casts out fear. For fear has to do with punishment, and whoever fears has not been perfected in love.

An anxious person shows the tendency to act according to the supposed expectations of “meaningful” others in order to gain approval from them. This dynamic is tragic, and Jesus formulates this very succinctly in the Gospels (Matthew 16:25a-26a):

“For whoever would save his life will lose it. For what will it profit a man if he gains the whole world and forfeits his soul?”

People who, because of anxious insecurity or romantic megalomania, dream of a utopian paradise of happiness (“the perfect partner” or “the perfect job” or even “the perfect society”), very often show masochistic tendencies. People indeed would literally sell their body and soul if you can convince them that they could gain “the whole world” by doing so. If you suffer from low self-esteem or, at the other end of the spectrum, from a superiority complex, then you’re no longer interested in yourself and others. You’re only interested in others to the extent to which they satisfy your craving for approval. Moreover, they no longer maintain a relationship with you, but with the image you present of yourself. In short, a person who models himself after an image that should produce approval is, eventually, not recognized for who he is. Hence: “For whoever would save his life will lose it.”

Moreover, it’s not just that people sacrifice themselves to the concerns of a socially acceptable image. Sooner or later others will also be sacrificed in order to protect reputations and narcissistic self-concepts. That’s precisely why Jesus reacts against the concern for socially acceptable images.

Everyone who acts according to the desire for approval and loses himself is, actually, “dead”. In terms of the New Testament such a person “does not have eternal life abiding in him”. Indeed, he has to constantly adjust his identity to ever changing and thus transient images in order to socially remain at the top of the game. If you want to win the competition for social success, then you will have difficulty accepting that someone else is equally successful and you might become jealous. And when you can only see the other as a rival for your own position, you will want to see him disappear. Sometimes literally. That’s what the famous myth of Cain and Abel, from the book of Genesis, is all about. Both brothers offer a gift. But Cain cannot stand that the gift of his younger brother is more appreciated. This shows that Cain did not offer a gift because of love, to make someone happy – otherwise he would be glad that his brother’s gift results in happiness –, but because of his desire for approval. Biblically speaking, acts because of “love of an image that should produce (social) approval” are sinful, and they get in the way of “good” acts born out of “love of oneself and the other”. This doesn’t mean, however, that gaining approval or recognition is a bad thing as such. When you receive recognition and feel proud as a consequence of your actions, there shouldn’t be any problem. The murderous envy the archetypal Cain is suffering from can only arise because he lives in order to gain approval, because “being proud” is his goal. Because Cain is obsessively preoccupied with the things he misses, he remains blind to the attention he does receive. The New Testament radically resumes these motives, and Johns first letter thus formulates (1 John 3:11-15):

Everyone who acts according to the desire for approval and loses himself is, actually, “dead”. In terms of the New Testament such a person “does not have eternal life abiding in him”. Indeed, he has to constantly adjust his identity to ever changing and thus transient images in order to socially remain at the top of the game. If you want to win the competition for social success, then you will have difficulty accepting that someone else is equally successful and you might become jealous. And when you can only see the other as a rival for your own position, you will want to see him disappear. Sometimes literally. That’s what the famous myth of Cain and Abel, from the book of Genesis, is all about. Both brothers offer a gift. But Cain cannot stand that the gift of his younger brother is more appreciated. This shows that Cain did not offer a gift because of love, to make someone happy – otherwise he would be glad that his brother’s gift results in happiness –, but because of his desire for approval. Biblically speaking, acts because of “love of an image that should produce (social) approval” are sinful, and they get in the way of “good” acts born out of “love of oneself and the other”. This doesn’t mean, however, that gaining approval or recognition is a bad thing as such. When you receive recognition and feel proud as a consequence of your actions, there shouldn’t be any problem. The murderous envy the archetypal Cain is suffering from can only arise because he lives in order to gain approval, because “being proud” is his goal. Because Cain is obsessively preoccupied with the things he misses, he remains blind to the attention he does receive. The New Testament radically resumes these motives, and Johns first letter thus formulates (1 John 3:11-15):

For this is the message that you have heard from the beginning, that we should love one another. We should not be like Cain, who was of the evil one and murdered his brother. And why did he murder him? Because his own deeds were evil and his brother’s righteous. Do not be surprised, brothers, that the world hates you. We know that we have passed out of death into life, because we love the brothers. Whoever does not love abides in death. Everyone who hates his brother is a murderer, and you know that no murderer has eternal life abiding in him.

For this is the message that you have heard from the beginning, that we should love one another. We should not be like Cain, who was of the evil one and murdered his brother. And why did he murder him? Because his own deeds were evil and his brother’s righteous. Do not be surprised, brothers, that the world hates you. We know that we have passed out of death into life, because we love the brothers. Whoever does not love abides in death. Everyone who hates his brother is a murderer, and you know that no murderer has eternal life abiding in him.

The New Testament authors are convinced that the possibility to abandon the narcissistic competition for “the highest social status” has to do with a love that is embodied exceptionally in Jesus of Nazareth. They try to clarify that Jesus of Nazareth time and again allows people to “resurrect” – following the just mentioned words from John’s first letter: Jesus allows people “to pass out of death (i.e. a life for the sake of socially acceptable images) into life (an authentic life in love)”. Of course this entails many risks. If you no longer live in accordance with a world dominated by the struggle for prestige, because you want to take sides with the victims of that struggle, then you should “not be surprised that the world hates you”. Nevertheless, instead of asking himself what he should do in order to “fit in”, Jesus asks himself how he can accomplish “that those who do not fit in may fit in again”. A prayer ascribed to Francis of Assisi (1181/1182-1226) is but one example from the Christian tradition that is a testimony to this dynamic: “Grant that I may not so much seek to be loved as to love…” This is the second aspect of Jesus’ aforementioned iconoclasm. It’s also, at the same time, a third argument against his depiction as a narcissist. When Jesus takes sides with the common enemy or easy victim of a united group, he does not have the ambition to alienate that person from his social environment. Gurus who desire recognition from easily manipulated victims do just that. Jesus, on the contrary, time and again challenges communities to truly respect the individuals they marginalized before. For instance, when he cures the Gerasene demoniac (Mark 5:1-20) he forbids this former “village idiot” to follow him. Instead, Jesus sends him back home. It’s but one case that shows how Jesus’ aim is not to make himself popular among a number of followers, although popularity often is an unintentional consequence of his actions. The Gospel stories show how Jesus, apart from himself, wants to create the possibility of loving relationships between people, relationships which are no longer based on sacrifices as a consequence of the love of socially acceptable images. In short, the paradoxical dynamic of love Jesus tries to obey alienates people from their own narcissistic identities (collective or individual), and opens up the road to more authentic relationships which refuse the sacrifice of a former “enemy”.

As mentioned earlier, the behavior of Jesus is not without risks. When you constantly take sides with “the socially crucified” chances are that you will be crucified yourself too. This is exactly what happens. To make things clear, though: Jesus doesn’t secretly hope that he will be crucified to enter into history as a “hero”. When he takes sides with the adulteress he doesn’t want the mob to stone her as well as him. At least that’s what the Gospels strongly suggest. They also show, at different times, that Jesus flees whenever he notices that people want to kill him. Eventually, however, he can no longer escape the murderous web of his adversaries. As is Martin Luther King (1929-1968) in later times, Jesus is well aware of certain death threats, and he warns his apostles that there will be a point of no return. At first Peter doesn’t want to accept this, whereon Jesus reproaches him (Matthew 16:22-26):

Peter took Jesus aside and began to rebuke him. “Never, Lord!” he said. “This shall never happen to you!” Jesus turned and said to Peter, “Get behind me, Satan! You are a stumbling block to me; you do not have in mind the concerns of God, but merely human concerns.” Then Jesus said to his disciples, “Whoever wants to be my disciple must deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me. For whoever wants to save their life will lose it, but whoever loses their life for me will find it. What good will it be for someone to gain the whole world, yet forfeit their soul? Or what can anyone give in exchange for their soul?”

Jesus knows that Peter tries to seduce him to establish himself as a mighty king. Apparently Peter does not see what kind of leadership Jesus actually envisions, although he called Jesus “the Messiah” a little earlier. Once again Jesus rejects the temptation to sell his soul to a competition with “the kings of this world”. Indeed he knows how such a struggle demands sacrifices, that people lose themselves and others in such a struggle. He does not want that. Instead he wants to generate another dynamic. Jesus claims that “whoever loses their life for him will find it”. Again this is only logical. When you take sides with the marginalized fellow man, you no longer lose yourself to the idolatry of socially acceptable images, and thus you “find” yourself. Jesus eventually takes the position of all those who are rejected. When his good friend Peter would take sides with him after Jesus is arrested, Peter indeed would no longer lose himself to a deceiving social profile.

Despite all Peter’s promises – which Jesus once again debunks as narcissistic illusions – Jesus eventually finds himself alone. As announced, Jesus refuses the mimetic rivalry (words of René Girard) with “the rulers of this world” who establish their power on the basis of sacrifices. Paradoxically this means that Jesus, if he continues to take sides with whoever is about to become a victim, might no longer experience mercy at some point, and that he should be prepared to die himself. In other words, this means that Jesus might have to “sacrifice himself against sacrifice”. Again, because Jesus refuses to “sacrifice himself” in favor of an all-controlling position of power, and because he takes sides with “the crucified”, he runs the risk of being crucified himself. When you take sides with the bullied, you run the risk of being bullied yourself. So when Jesus prays to his “Father” to, if possible, take “the cup of suffering and death” from him, and then says that “not his will but the will of his Father be done” (Matthew 26:39), it makes no sense to interpret this sentence as though Jesus all of a sudden believes that God “desires sacrifice”. Throughout the Gospel Jesus indeed is convinced that his Father “desires mercy, not sacrifice” (Matthew 9:13), and he acts accordingly: whenever people are about to be sacrificed, Jesus intervenes. However, if Jesus refuses to enter into a rivalry with those who establish their rule on the basis of sacrifices, there is no other option than to consider the possibility of his own death. Obeying the love that desires mercy, Jesus cannot launch a civil war to the detriment of society. That’s why he says, when questioned by Pilate after being arrested (John 18:36): “My kingdom is not of this world. If it were, my servants would fight to prevent my arrest. But now my kingdom is from another place.”

Despite all Peter’s promises – which Jesus once again debunks as narcissistic illusions – Jesus eventually finds himself alone. As announced, Jesus refuses the mimetic rivalry (words of René Girard) with “the rulers of this world” who establish their power on the basis of sacrifices. Paradoxically this means that Jesus, if he continues to take sides with whoever is about to become a victim, might no longer experience mercy at some point, and that he should be prepared to die himself. In other words, this means that Jesus might have to “sacrifice himself against sacrifice”. Again, because Jesus refuses to “sacrifice himself” in favor of an all-controlling position of power, and because he takes sides with “the crucified”, he runs the risk of being crucified himself. When you take sides with the bullied, you run the risk of being bullied yourself. So when Jesus prays to his “Father” to, if possible, take “the cup of suffering and death” from him, and then says that “not his will but the will of his Father be done” (Matthew 26:39), it makes no sense to interpret this sentence as though Jesus all of a sudden believes that God “desires sacrifice”. Throughout the Gospel Jesus indeed is convinced that his Father “desires mercy, not sacrifice” (Matthew 9:13), and he acts accordingly: whenever people are about to be sacrificed, Jesus intervenes. However, if Jesus refuses to enter into a rivalry with those who establish their rule on the basis of sacrifices, there is no other option than to consider the possibility of his own death. Obeying the love that desires mercy, Jesus cannot launch a civil war to the detriment of society. That’s why he says, when questioned by Pilate after being arrested (John 18:36): “My kingdom is not of this world. If it were, my servants would fight to prevent my arrest. But now my kingdom is from another place.”

This quote follows earlier claims by Jesus. For instance when Pharisees try to test him once more. Strangely enough, they start with the observation that Jesus doesn’t care about what other people might think of him, and at the same time they suggest that this “arrogant man of Nazareth” (at least from their perspective) apparently just needs the approval from God. If Jesus would answer (see below) their question by saying that the Jews should pay the imperial tax, he would lose his popularity among the common people – he would indeed be perceived as a “collaborator” of the Roman occupier. If, on the other hand, he would say that Jews should not pay the tax, then the envious Jewish authorities could sell him as a dangerous revolutionary to the Roman government, and they thus could get rid of the man they consider a rival to their own position. However, Jesus is not driven by a desire for this or that approval or power. He does not compete with the kings and rulers of this world to become “the most powerful ruler”. His answer reveals the projected narcissism of the Pharisees in a magnificent way, and it also makes clear that the God of Christ – love – is no surrogate for a possible lack of social approval (Matthew 22:15-21):

The Pharisees went out and laid plans to trap Jesus in his words. They sent their disciples to him along with the Herodians. “Teacher,” they said, “we know that you are a man of integrity and that you teach the way of God in accordance with the truth. You aren’t swayed by others, because you pay no attention to who they are. Tell us then, what is your opinion? Is it right to pay the imperial tax to Caesar or not?” But Jesus, knowing their evil intent, said, “You hypocrites, why are you trying to trap me? Show me the coin used for paying the tax.” They brought him a denarius, and he asked them, “Whose image is this? And whose inscription?” “Caesar’s,” they replied. Then he said to them, “So give back to Caesar what is Caesar’s, and to God what is God’s.”

Jesus also reproaches his disciples when he finds them in an envious quarrel concerning the question who would be “the greatest” among them. The leadership of Jesus is not based on an acquisition of power in the sense of “control”, or on the exclusion of possible rivals. Vulnerable love is creative and grants, from her abundance, others the grace and power “to be” (Luke 22:24-27):

A dispute arose among the disciples of Jesus as to which of them was considered to be greatest. Jesus said to them, “The kings of the Gentiles lord it over them; and those who exercise authority over them call themselves Benefactors. But you are not to be like that. Instead, the greatest among you should be like the youngest, and the one who rules like the one who serves. For who is greater, the one who is at the table or the one who serves? Is it not the one who is at the table? But I am among you as one who serves.

Because of the love he lives by, Jesus indeed is able to – in the mocking words of his adversaries – “save others, but not himself” (Matthew 27:42). When Jesus takes sides with the social outcasts, he becomes dependent on the reactions of others: will they show mercy, or will they demand sacrifices? Believing in “a God almighty” in a Christian sense thus has nothing to do with believing in a God as “the master of puppets” (contrary, for instance, to Etienne Vermeersch’ depiction of the Christian understanding of God). It means believing in a love that, independent of its eventual result and only “almighty” and “creative” in this sense, gives itself time and again (even after being crucified…). See for example the comments the influential Catholic theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar (1905-1988) made about the Nicene Creed (“Credo”), when he explains the sentence “I believe in one God, the Father Almighty, maker of heaven and earth…” (from Credo – Overwegingen bij de Apostolische Geloofsbelijdenis, Schrift en Liturgie 17, Abdij Bethlehem Bonheiden, 1991, p.34-35; vertaling: Benedictinessen van Bonheiden; English translation: E. Buys): “It is… essential, first of all, to see the immeasurable power of the Father as the power to give oneself, this means as the power of his love, and not as an arbitrary power of being able to do this or that. And it is equally essential to understand the almighty power of the love of the Father not as something fierce that is rather suspicious, not as something that goes against logic, because the “giving of himself” is at the same time a reflection of himself, an expression of himself (Hebrews 1:3). […] The power by which the Father expresses himself is not forced, but is also source of all freedom, once again not in the sense of arbitrary power, but in the sense of the love that abandons itself in a state of majestic self-determination.”

In the light of a human world that is obsessed by a desire for power in the sense of control this vulnerable, yet nevertheless independent love, is foolish. Hence the apostle Paul writes (1 Corinthians 1:23): “We preach Christ crucified: a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles.” Christians believe that the love of Christ has the power not to imitate the one who “strikes” but, on the contrary, “offers the other cheek” (Luke 6:29 – thus this love does not depend on what has been done and creates new possibilities for relationships “ex nihilo”). And this infinitely, “seventy times seven” (Matthew 18:27). Indeed, if you are a realist, then relationships between people in our never perfect human world are only possible when people realize that “nobody is perfect”. So mutual forgiveness is a must… The dimension of forgiveness creates the free space wherein people may come to accept themselves and bear responsibility for their mistakes without being “crushed” under guilt (of course, again, this cannot be guaranteed). People who learn to love themselves no longer have to hide behind narcissistic types of self-righteousness (on the other hand, the perversion of forgiveness does maintain narcissistic self-concepts). They no longer have the need to “scapegoat” others, to pass their guilt or shame on to others… Instead they are able to take responsibility for their own actions. A man who loves himself no longer approaches others according to his need for approval, but from his abundance – from what he has to offer –, and is thus able to truly love others (others he no longer needs to fill his own “voids”). Christians believe that the salvation of the world lies in the imitation of the dynamic of the love that is revealed in an exceptional (though not exclusive) way in the life of Jesus of Nazareth – who is therefore called “the Christ”.

A final argument, at least for now, against the depiction of Jesus as the ultimate narcissist is the observation that Jesus hasn’t written anything himself. Everything that he says, apart from the debatable ipsissima verba, is put into his mouth by others who want to clarify how Jesus was experienced. In this sense he does not “brag” about himself.

3. NARCISSISTIC ATHEISM

The sustained logic in the Gospels and the further developed Christian tradition points in the direction of “Jesus as ultimate, sometimes painfully consistent realist in a world of narcissists”. Certain people, despite all rational arguments, remain blind to this logic. However, this has nothing to do with a supposed “vagueness” of the Christian resources, but once again with a stubborn narcissism.

Fundamentalist Christians, for instance, quite often believe in a God almighty in an actually non-Christian sense (see higher). They have difficulty abandoning a view of God that is not compatible with the understanding of God that can be derived from the Christ figure in the Gospels. Their ultimate defense of unsustainable reasoning often sounds like, “God works in mysterious ways”. That’s their way of ending any type of dialogue, discussion or self-criticism. But some atheists as well rather stick to their ideas of the Christian story (and theology or even religion in general) than question them. Narcissistic, intellectual complacency can be found in every corner. Especially when a rather hostile opinion about the Christian story is identity enhancing. Comments by some atheists, whose perception is often guided by negative emotions, on this post are thus predictable: “This is a particular type of interpretation, and it is all relative eventually. What is there to know? Theology allows everything!” Once again the lazy and cowardly “argument” of “mysterious ways” comes to the fore. Well, if you believe in rational arguments, sustained by scientific research (from literary criticism to history and anthropology), you will find that one interpretation is better and more plausible than the other. Everything is not that “mysterious” or “vague” or “incoherent” as it seems.

Fundamentalist Christians, for instance, quite often believe in a God almighty in an actually non-Christian sense (see higher). They have difficulty abandoning a view of God that is not compatible with the understanding of God that can be derived from the Christ figure in the Gospels. Their ultimate defense of unsustainable reasoning often sounds like, “God works in mysterious ways”. That’s their way of ending any type of dialogue, discussion or self-criticism. But some atheists as well rather stick to their ideas of the Christian story (and theology or even religion in general) than question them. Narcissistic, intellectual complacency can be found in every corner. Especially when a rather hostile opinion about the Christian story is identity enhancing. Comments by some atheists, whose perception is often guided by negative emotions, on this post are thus predictable: “This is a particular type of interpretation, and it is all relative eventually. What is there to know? Theology allows everything!” Once again the lazy and cowardly “argument” of “mysterious ways” comes to the fore. Well, if you believe in rational arguments, sustained by scientific research (from literary criticism to history and anthropology), you will find that one interpretation is better and more plausible than the other. Everything is not that “mysterious” or “vague” or “incoherent” as it seems.

The questions “What claims does the Christian story make and what is the essence of the Christian faith?” do have answers which are, from a rational and scientific point of view, more plausible than others. Whatever narcissists may claim. Theists as well as atheists may set up an inquiry to settle those matters.

A debate (on October 17, 2013), organized by Het Denkgelag about “The Limits of Science” – a conversation between Daniel Dennett, Lawrence Krauss, Massimo Pigliucci, and Maarten Boudry (moderator) – illustrated quite comically some of the unquestioned narcissistic prejudices guiding the discussion on religion in so-called “new atheist” quarters.

This tea party of atheists only sporadically rose above the level of musings from a bar, but maybe this was done deliberately to reach a big audience. Anyway, you would think this conversation was “for laughs” if they wouldn’t take themselves so seriously. For instance, it was quite embarrassing how biologist and philosopher Massimo Pigliucci and philosopher Daniel Dennett had to explain to physicist Lawrence Krauss that the criteria to judge whether or not a human action is moral cannot be defined by science. Once the criteria are established – perhaps after long rational considerations – science might help, of course, to produce information concerning the question how to realize a certain type of morality. If you believe, for instance, that the moral character of a deed is determined by the level of happiness it produces, you may scientifically gather knowledge concerning the degree to which a certain deed results in happiness. After you’ve defined what “happiness” actually entails, that is. Which once again implies that a philosophical, rational discussion on the nature of happiness precedes every possible scientific research. It is very unusual that these basic insights have to be dealt with in such a lengthy fashion (almost twenty minutes explicitly) on an evening that pretends to be a high mass of rationality. The initial “discord” between Pigliucci and Krauss thus had no intellectual power whatsoever. It was due to ignorance from the part of Krauss. Pigliucci eventually summarizes the course of philosophy for freshmen (between minutes 42:40 and 44:00 of the conversation):

“Nobody in his right mind, no philosopher in his right mind, I think, is saying that empirical facts, or even some scientific facts – as should be clear by now, I take a more restrictive definition of science or concept of science than Lawrence does – but even if we want to talk about empirical facts, broadly speaking, nobody is denying […] that empirical facts are relevant to ethical decisions. That’s not the question. The question is […] that the empirical facts, most of the times, if not all the times, in ethical decision making, are going to underdetermine those decisions, those value judgements that we make. So the way I think of ethics is of essentially ‘applied rationality’. You start with certain general ideas. Are you adopting a utilitarian framework? Are you adopting a deontological framework, a virtue ethics framework or whatever it is? And then that essentially plays the equivalent role of, sort of, general axioms, if you will, in mathematics or general assumptions in logic. And from there you incorporate knowledge, empirical knowledge, about, among other things, what kind of beings humans are. Ethics, let’s not forget, is about human beings.”

Moreover, Pigliucci was right to point out that Sam Harris makes a similar mistake as Krauss in his book The Moral Landscape. Of course Harris made a lot of money from the sales of his book, but looked at more closely it is an intellectual misleading of the people that is low on substance. No wonder Pigliucci has to say the following on Harris’ book (48:22-48:44):

“Sam Harris, who you [Maarten Boudry] introduced as a philosopher, I would characterize mostly as a neuroscience based person. I think he would do it that way. When I read his book, ‘The Moral Landscape’ which promised a scientific way of handling ethical questions. I got through the entire book and I didn’t learn anything at all, zero, new about ethics, right?”

“Sam Harris, who you [Maarten Boudry] introduced as a philosopher, I would characterize mostly as a neuroscience based person. I think he would do it that way. When I read his book, ‘The Moral Landscape’ which promised a scientific way of handling ethical questions. I got through the entire book and I didn’t learn anything at all, zero, new about ethics, right?”

Apart from that, Pigliucci is irritated by a number of claims done by some scientists, who speak of philosophy (of science) without having a clue what they are talking about. He once again reacts against certain statements by Krauss (1:12:57-1:13:28):

“First of all, most philosophy of science is not at all about helping scientists answer questions. So it is no surprise that it doesn’t. So when people like your colleague Stephen Hawking – to name names – starts out a book and says that philosophy is dead because it hasn’t contributed anything to science, he literally does not know what he is talking about. That is not the point of philosophy of science, most of the time.”

In short, the discord that threatened to arise between Pigliucci and Dennett on the one hand, and Krauss on the other, was resolved time and again by giving Krauss some “extra classes”. Pigliucci had the courtesy to do this somewhat indirectly, but it is clear that his comments on Stephen Hawking were a way of reproaching Krauss for his “red herring” (the repeated remark of Krauss that philosophy (of science) does not contribute anything directly to science is irrelevant because it is not the aim of philosophy). Pigliucci ended this discussion with an analogy (1:13:59 – 1:14:12):

“So, yes, philosophy of science doesn’t contribute to science, just like science does not contribute to, you know, English literature. Or literary criticism, whatever you want to put it. But so what, no one is blaming the physicists for not coming up with something new about Jane Austen.”

You would expect that Pigliucci is consistent about this analogy when he tries to define different areas of research, but when it came down to theology he too took on the unreflective attitude of Krauss. Boudry and Dennett harmoniously joined their two friends. Apparently the atheists had found a “dead” common enemy, theology, that united them (1:13:46 – 1:13:48):

Lawrence Krauss: “Well, theology, you could say is a dead field…”

Massimo Pigliucci: “Yes, you can say that. Right!”

Already at the beginning of the evening the gentlemen were sure about this issue:

20:11 – 20:21 Maarten Boudry: “Do you think that science, no matter how you define it, or maybe it depends, has disproven or refuted god’s existence?”

21:10 – 21:30

Lawrence Krauss: “What we can say, and what I think is really important, is that science is inconsistent with every religion in the world. That every organized religion based on scripture and doctrine is inconsistent with science. So they’re all garbage and nonsense. That you can say with definitive authority.”

21:50 – 22:42

Massimo Pigliucci: “I get nervous whenever I hear people talking about ‘the god hypothesis’. Because I think that’s conceding too much. Well, it seems to me, in order to talk about a hypothesis, you really have to have something fairly well articulated, coherent, that makes predictions that are actually falsifiable. All that sort of stuff. […] All these [god-] concepts are incoherent, badly put together, if put together at all. […] There is nothing to defeat there. It’s an incoherent, badly articulated concept.”

The previous chapter, about the question whether or not the Jesus character of the New Testament is a narcissist, is a first falsification of the claims made by Krauss and Pigliucci. Organized religion, based on so-called revelation, scripture and dogma, is not by definition inconsistent with science. Moreover, the New Testament view of God is not at all incoherent. A short summary of the previous chapter may clarify this.

The people who are behind the traditions which eventually produce the New Testament writings believe that God is revealed – at least at a human level – in a love that enables human beings to accept themselves and others in an authentic way. This not directly visible love has the potential to emancipate people from a life lived for the sake of (social) approval or, in other words, from a life lived for the sake of an untruthful image that should produce some sort of appreciation by others. The New Testament authors thus define “salvation” as follows: people who realize that they are loved for who they are (with their flaws and limitations) are saved, more and more, from the tendency to sacrifice themselves and others to “the idolatry of social prestige”. At the same time the New Testament authors are convinced that this love, that refuses those sacrifices, is exceptionally (though not exclusively) embodied in Jesus of Nazareth, who is therefore called “the Christ” and is depicted as the example par excellence that demands imitation.

By applying literary criticism, among other things, the atheist gentlemen may discover whether or not this characterization of the New Testament claims contains the essence of the Christian faith. Maybe they should do that before they surrender themselves to the narcissistic arrogance of being able to judge “all theology”. It is strange that Pigliucci is irritated by the mistakes some scientists make concerning “philosophy” while he makes a similar mistake concerning “theology”. Theology today has to do with interdisciplinary scientific research into the concept of God held by certain religious traditions, and its possible implications. This has nothing to do with the question whether or not someone believes in God. To use an analogy: eventually you don’t have to agree with Shakespeare’s view of human nature in order to pursue an investigation into the anthropology that can be derived from his plays. In short, the questions theologians concern themselves with are from a fundamentally different nature than the questions scientists concern themselves with, so there shouldn’t be any fundamental conflicts between these two areas of research. In the aforementioned analogy of Pigliucci: “No one is blaming the physicists for not coming up with something new about Jane Austen.”

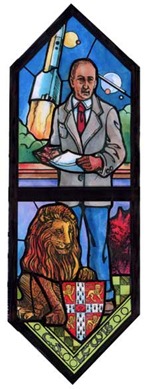

Maybe Pigliucci and co. should take Georges Lemaître as an example. This Belgian Catholic priest and famous physicist (founder of the “Big Bang” hypothesis among others) clearly distinguishes the questions of modern science from the questions the New Testament authors deal with. In fact, according to Lemaître, questions of modern science have nothing to do with theology, and vice versa. The Christian scientist thus cannot let his faith be of any importance for his scientific work. Some quotes from Lemaître, taken from an article by Joseph R. Laracy (click to read) clarify his position regarding the relationship between theology and modern science:

Maybe Pigliucci and co. should take Georges Lemaître as an example. This Belgian Catholic priest and famous physicist (founder of the “Big Bang” hypothesis among others) clearly distinguishes the questions of modern science from the questions the New Testament authors deal with. In fact, according to Lemaître, questions of modern science have nothing to do with theology, and vice versa. The Christian scientist thus cannot let his faith be of any importance for his scientific work. Some quotes from Lemaître, taken from an article by Joseph R. Laracy (click to read) clarify his position regarding the relationship between theology and modern science:

“Should a priest reject relativity because it contains no authoritative exposition on the doctrine of the Trinity? Once you realize that the Bible does not purport to be a textbook of science, the old controversy between religion and science vanishes . . . The doctrine of the Trinity is much more abstruse than anything in relativity or quantum mechanics; but, being necessary for salvation, the doctrine is stated in the Bible. If the theory of relativity had also been necessary for salvation, it would have been revealed to Saint Paul or to Moses . . . As a matter of fact neither Saint Paul nor Moses had the slightest idea of relativity.”

“The Christian researcher has to master and apply with sagacity the technique appropriate to his problem. His investigative means are the same as those of his non-believer colleague . . . In a sense, the researcher makes an abstraction of his faith in his researches. He does this not because his faith could involve him in difficulties, but because it has directly nothing in common with his scientific activity. After all, a Christian does not act differently from any non-believer as far as walking, or running, or swimming is concerned.”

“The writers of the Bible were illuminated more or less — some more than others — on the question of salvation. On other questions they were as wise or ignorant as their generation. Hence it is utterly unimportant that errors in historic and scientific fact should be found in the Bible, especially if the errors related to events that were not directly observed by those who wrote about them . . . The idea that because they were right in their doctrine of immortality and salvation they must also be right on all other subjects, is simply the fallacy of people who have an incomplete understanding of why the Bible was given to us at all.”

The question about the meaning of “salvation” in the light of the New Testament indeed is different from, for instance, the question how and why objects fall down. That’s how plain and simple an insight can be in order to stop battling windmills like some heroic but mad and narcissistic Don Quixote. But anyway, a man shouldn’t foster any illusions: Maarten Boudry, Lawrence Krauss and other similar atheists rarely, if ever, rise to the challenge to question their belief regarding the nature of theology in a scientific way. But maybe this is just the narcissism of a theologian speaking now 🙂 ?

Nonetheless, Boudry claims that he holds science in high regard. His question for the audience at the beginning of the evening already suggests this (16:58-17:30): “Do you think that science is the sole source of knowing?” A lot of people answered affirmatively. But what does that mean when you meet another person? Does that mean that you don’t ever know that person when you have not analyzed and described him or her scientifically? And, on the other hand: does that mean that you can know a person merely by detailed scientific descriptions, without ever meeting him or her? A bit odd, to say the least. Somehow you would expect that you know the person who reveals himself to you, every day, honestly and faithfully, better than the person you know from scientific descriptions but have never met. Or would it be true that the “real” and “complete” identity of a person (his “soul”, to use an age old word) can be reduced to what science may say about him? Again, a bit odd to “lock up” someone’s personality in scientific descriptions…

Anyway, of course Maarten Boudry, Massimo Pigliucci, Lawrence Krauss and Daniel Dennett are more than just intellectual narcissists. It just so happens that they don’t really show any sign of self-criticism regarding theology. And that’s a pity, really, because scientifically enhanced theological research (based on the historical-critical method) could prevent some of the excesses of fundamentalism. Sure, Boudry et al. are delivering the goods in their own fields of research. However, nothing human is alien to humans… Every once in a while, everyone is a narcissist, no? There might be one exception, though…